“Give to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s,” Jesus famously said in Mark’s gospel. But how this relates to the relationship between religion and politics is a topic Christians have debated for centuries. In 426, in City of God, Augustine argued that Christians should focus on eternal things and leave earthly matters to empire. But as the church grew more powerful, it became a political force, provoking criticism from many thinkers and reformers. In his 14th-century treatise Monarchia, for instance, poet Dante Alighieri argued that papal and imperial authority should exist in two separate spheres.

The idea that church and state should be separate became more popular during the Enlightenment era, when the United States was founded. Yet the debates that happened for centuries prior to this suggest that separation of church and state is not a purely secular ideal. And as the boundary between church and state grows thinner, the question of what we owe to God and to Caesar has taken on a new urgency.

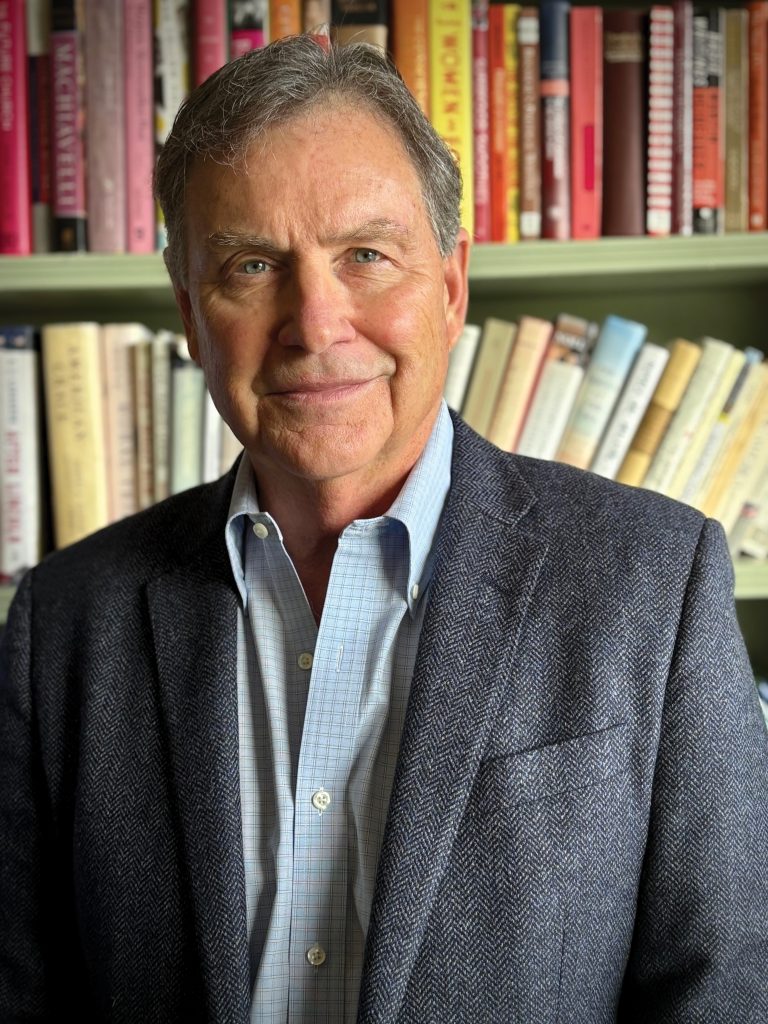

On a recent episode of the Glad You Asked podcast, political philosopher and activist Stephen F. Schneck talked about where the ideal of separation and church and state comes from and clarified the institutional church’s view on this matter. Separation of church and state, Schneck pointed out, is closely connected with the rights of conscience and freedom of religion—matters that Catholics take seriously.

“Separation of church and state” has become something of a catchphrase in current political discourse. Where did the idea originate and what does it really mean?

The idea has its origins in the European religious wars between Catholics and Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. I think that we all know enough history to realize just how horrible those were.

Its origin also lies, to a certain extent, in the philosophy of humanism, which stems from that same historical period and which celebrates the dignity and the freedom of individual conscience. So you could say that its provenance lies with people like Erasmus, John Locke, René Descartes, and so on. Many of our current ideas about things like human rights and liberal democracy emerge from that same milieu of humanist thought in the 16th and 17th centuries.

What does the Catholic Church say about the relationship between faith and government?

The key document regarding the separation of church and state in the Catholic world is the church’s teaching as outlined in Dignitatis Humanae (On the Right of the Person), which was written by Paul VI in 1965.

The Catholic Church and the Johnson Amendment

In the United States, churches as well as certain other nonprofit entities are prohibited from endorsing political candidates if they want to keep their tax-exempt status with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). This restriction is due to a provision in the U.S. tax code called the Johnson Amendment, named for then-senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas.

In recent years, some political figures have suggested that the amendment restricts freedom

of speech and should be repealed. In 2016, Donald Trump worried that he was missing out on endorsements from religious groups because they were afraid of losing their tax-exempt status. After his election, in 2017, he signed an executive order to ease the amendment’s restrictions.

Defenders of the Johnson Amendment point out that churches already have fewer reporting requirements than other nonprofit entities and that religious leaders are free to endorse candidates, so long as they do so in their status as private citizens. Repealing the amendment, they argue, would threaten religious independence, as this would open the door to political manipulation.

Repealing the Johnson Amendment might also yield a situation in which powerful lobbying groups weaponize churches for their own ends. LaShawn Y. Warren, vice president of the Faith and Progressive Policy Initiative at the Center for American Progress, points out in an article on the organization’s site that without the Johnson Amendment, “billionaire donors could give anonymously, while simultaneously receiving a charitable tax deduction. Such an ability could exacerbate the lopsided influence of outside money in American elections.” According to these and other arguments, the Johnson Amendment, rather than restricting religion, actually serves to protect it.

That document, which is an apostolic exhortation, somewhat echoes the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, in that it advocates for the free exercise of religion in society. Yet it also insists that both individual faith and institutionalized religion should be free from coercion by government. Dignitatis Humanae has been endorsed and enlarged by Pope St. John Paul II, by Benedict XVI, and by Pope Francis. So this is now a pretty central teaching in the church’s social magisterium.

Lately, the line between church and state is being blurred. The IRS has largely stopped enforcing the Johnson Amendment, which restricts ministers from endorsing candidates from the pulpit. What are the implications of these changes?

Well, the blurring is happening in a number of places, not just in regard to the Johnson Amendment. For example, we’re seeing organized and strident calls from several quarters in our politics asking government to promote religion, particularly Christianity, and even for government to be an instrument of Christianity.

These calls range from fringe notions like “Trump is God’s messenger” to more traditional efforts, such as groups demanding that the Bible be taught in public schools and that the Ten Commandments be posted in public places, and so forth.

I would encourage Catholics to remember that we created our system of Catholic schools and hospitals back in the 19th century so we could practice our faith freely in a society that seemed to want to impose a version of Protestantism on Catholics. Catholics in the 19th century knew firsthand why separation of church and state was so important.

In regard to the Johnson Amendment: I’m no expert on the IRS and tax laws as it relates to campaigns and so forth, but I can make a couple of general remarks.

The Johnson Amendment was named for President Lyndon Johnson. It was put in place back in the 1950s and argued that organizations like private schools, charities, and especially churches shouldn’t be working for political campaigns. If you think about churches in that context, you can see why the Johnson Amendment works to help protect the separation of church and state.

In the past year, President Trump instructed the IRS through an executive order to no longer prosecute churches that engaged in political campaigning. This would weaken the Johnson Amendment.

I think that’s a big mistake. First, it would open the door for certain religious groups to become even more influential in shaping government. And of course, we have to ask what that means for those of us who don’t belong to those groups.

But secondly, I think it’s a risk to religion. We’ve already seen Americans, particularly young people, turning away from religion because they think that it’s too political. Things like this would only make matters worse. I want my church to be about the gospels and the sacraments, not about political party platforms.

Some critics have argued that Christian nationalism is starting to fill the space once held by the ideal of religious pluralism. Do you think that’s accurate?

I suppose it is. The promise of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights was that Americans would be free to practice their faith, free to believe according to their personal discernment about matters of religion. So people of all faiths from all over the world came to the United States as a land of religious freedom.

Now, of course, we know that promise was not always kept. Catholics, Mormons, Jews, and other religions and denominations have suffered horrible discrimination and sometimes even persecution. But the promise of religious freedom was always there. Christian nationalists essentially want to erase that promise. And frankly, not only is that not American, but it’s also not Christian.

What would you say to the argument that, if Christianity is true, the nation should be run on Christian principles? I could even say, a truly Christian nation would welcome the stranger and care for the poor. Wouldn’t we want that?

My whole career in public life has been advocating for government to do the right thing, as inspired by my Catholic faith. So naturally, I’m very much in favor of a role for faith in public life. But first, I think the role of faith should come from below. By that, I mean that each of us as citizens should come to public life inspired by our faith. As citizens, we should try to move the government in the direction of what our faith is calling us to do.

And secondly, my understanding of the importance of human dignity and the primacy of free conscience means that we really must allow for and respect people who have beliefs that are different from mine. And they should be able to advocate for whatever their faith inspires them to do in public life as well.

Religious nationalism doesn’t come from below. It would have the state impose faith from above. And it would not allow for a diversity of religious beliefs, but would instead, because it’s all coming from the state and imposed by the power of the state, essentially be steamrolling over all the diversity of religion and replacing it with a single denominational interpretation of Christianity—or whatever the religion might be.

How does integralism relate to the questions about the relationship between church and state?

The easiest way to understand Catholic integralism is as a Catholic version of Christian nationalism. Catholic integralists believe that the state ought not to be secular or neutral in regard to things like values, but instead should be an instrument of the Roman Catholic Church and the church’s teachings.

In our traditional American and democratic way of thinking about society and public life, we believe the government should be guided by what citizens decide and limited by the rights of citizens. We live in a democracy, where government is supposed to be a servant to the people. As the Constitution says, we the people are sovereign.

Integralists believe that such sovereignty should really belong to the Catholic Church and that government should be guided and limited by the Catholic religion and its teachings. It’s really pretty hard to square with anything that we’ve come to know as Catholics in the United States.

What would a ethical relationship between church and state look like, based on the church’s social teachings?

I think Pope Benedict has some insightful things to say about this. One of his encyclicals, Deus Caritas Est (On Christian Love), speaks specifically to this. He starts by talking about Matthew’s gospel, where Jesus distinguishes between what belongs to Caesar and what belongs to God, separating church and state.

Pope Benedict takes this separation not to mean that there is no relationship between church and state at all, but rather that they are interrelated. Religion needs the state, Pope Benedict argues, to provide justice in light of the common good. Yet the state cannot do that without citizens who seek the common good.

And the question is, where do we find such citizens? Well, Benedict argues—and I love this argument—it’s religion that provides the state with citizens who have that care for the common good.

From this, Benedict concludes that the state ought never impose religion and that religion ought never rule over the state. Yet they need each other. The state needs to create a space or social order in which religions can thrive, guaranteeing religious freedom and harmony among the religions, so the state gets the citizens that are necessary for the state to succeed in pursuing the common good.

What’s at stake for ordinary Catholics if the wall between church and state continues to erode?

For all the reasons I’ve already mentioned, separation of church and state—and its corresponding notion of religious freedom—is bigger than just another political or legal disagreement. These are essential elements of our rights in this country. Eroding that wall of separation puts these rights at risk.

As I said before, Catholics especially should feel this in their bones. It wasn’t that long ago that an earlier version of nativist nationalism in the United States was prejudiced against our Catholic beliefs, calling them un-American. And if you and I haven’t experienced such discrimination in our lives today, we should ask our grandparents who do remember that kind of discrimination.

Let’s not allow that sort of thing to happen again to us as Catholics, or to any other religion in this country.

What are some practical ways we can respond to the erosion of the wall between church and state?

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has a number of documents that are just wonderful on these topics, and I would encourage everyone to go there. Dignitatis Humanae is a very readable apostolic exhortation that is available to everybody. More difficult reading might be some of the encyclicals like Deus Caritas Est. Pope Francis’ Fratelli Tutti (On Fraternity and Social Friendship) is another document I’d recommend.

It’s interesting to note that faith-based groups are out there on the ramparts trying to defend the separation of church and state, trying to protect religious freedom. And I would encourage Catholics to support, in whatever ways they can, efforts by these groups, many of which are either Catholic or have large Catholic contingents. Support their effort to protect both freedom of religion and separation of church and state, because these two are so closely intertwined.

How are faith communities engaging with politics in constructive ways that strengthen democracy?

Some of the faith-based groups I just mentioned are active in our national and local politics on these issues. This is, I think, a very hopeful sign for the future. Since protecting the wall of separation between church and state and protecting religious freedom also go hand in hand with protecting democracy from authoritarianism.

By protecting the rights of conscience, the rights of faith, the rights of belief, we’re really protecting our deepest freedoms from the state’s overreach. And if we lose those freedoms, democracy itself is compromised, possibly to the point of becoming meaningless. We should find inspiration and hope in the work of faith-based groups that are out there in the trenches doing the hard work of trying to defend these fundamental rights.

This article also appears in the November 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 11, pages 16-20). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Alejandro Barba

Add comment