In 2022 and 2023, Pope Francis invited community organizers from the United States to meet with him at the Vatican. Robert Hoo, a senior staff member and community organizer at West/Southwest Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), was one of 20 organizers who met with him in 2022.

“The first thing [Pope Francis] said was, ‘Thank you for visiting me. I’m sure it must have been very inconvenient for you to travel here,’ ” Hoo, an organizer at West/Southwest IAF since 2005, says. The IAF network had written a letter to Pope Francis highlighting their organizing work in recent years, including their Recognizing the Stranger initiative, which brings together immigrants and nonimmigrants to build relationships and is funded by the Catholic Campaign for Human Development (CCHD).

“We were really blown away by how down to earth [Pope Francis] is, what a good listener he is. He was very disarming,” Hoo says.

Pope Francis’ support for community organizing makes sense: Community organizing “dovetails the way that Pope Francis is leading the church,” says Richard Wood, president of the Institute for Advanced Catholic Studies at the University of Southern California. “He’s leading the church to become this alive space where people come as their whole selves,” says Wood, who has written about and taught community organizing for almost 30 years. “Organizing helps people create a world that’s addressing their concerns and challenges.” Indeed, the priorities of community organizing have much in common with synodality and Pope Francis’ vision for the church.

The Catholic roots of community organizing

Catholic social teaching has been a “huge part of West/Southwest IAF because we work so closely with many Catholic parishes and dioceses,” Hoo says.

IAF is a community-based organization, founded in 1940 by Saul Alinsky in the immigrant Chicago neighborhood Back of the Yards. Alinsky and others who started IAF, including Bishop Bernard Sheil, brought together meatpacking workers, fraternal organizations, unions, and parishes to create local accountability and citizen power in Chicago. Alinsky trained priests and other leaders how to organize across race, class, religious, and political lines. Today, IAF affiliates exist in 23 states plus Washington, D.C. and work with hundreds of religious congregations, nonprofits, civic organizations, and unions.

IAF created the modern model of faith-based organizing, inspired by labor organizing, which provides stability and institutional structure that enables organizing work to be effective and long-lasting.

Sister Leslie Dao, a mission novice with the Sisters of Providence, is a community organizer at the Coalition for Spiritual and Public Leadership (CSPL) in Chicagoland. She was born and raised in Vietnam and has worked with immigrants for more than 10 years in the United States. “Community organizing is Catholic social teaching in action,” Dao says.

In 1969, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) started an anti-poverty initiative called the Catholic Campaign for Human Development, which funds community organizing and economic development groups. It currently gives around $10 million annually to groups across the nation.

CCHD was founded after the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy. The U.S. bishops “saw there was a need to help people who weren’t being appreciated and respected,” says Ralph McCloud, executive director of CCHD. “Seeing where we find ourselves today, it’s some of the same issues. It’s just as important, if not more important now, to work toward bringing folks together.”

“Of religious denominations, the Catholic Church is the largest funder of community organizing,” says Lew Finfer, a Jewish community organizer who directs the Massachusetts Communities Action Network and has been organizing since 1970. “There’s also the long tradition of Catholic social teaching and the existence of and funding from CCHD.”

And yet, despite the support and funding of CCHD and the history of Catholic organizing in the United States, over the past few decades there has been a decline in Catholic parish participation in community organizing, Wood says.

“Twenty years ago, a solid 40 percent of churches around the country that were involved [in faith-based organizing] were Catholic. These days it’s probably a quarter,” Wood says. “I think the downside of that is the church is losing one of the best tools for actually having a voice in the wider world and addressing crucial issues, whether that’s climate change or the lack of jobs young people face. Organizing is better when there’s a vigorous Catholic involvement, but I also think the Catholic Church is better when there’s a vigorous organizing involvement.”

Changes in the priesthood have contributed in part to a decline in Catholic organizing over the years, Wood says. “The Catholic priesthood has become less out of working-class settings and more out of suburban settings. The younger clergy these days don’t often have the same instincts for [community organizing]. The exceptions to that are out of some of the religious communities and some of the younger Latino, immigrant, Black, and Southeast Asian priests and communities.”

Catholic organizers have felt this shift, and in 2023, a conference at the University of San Francisco called “Prophetic Communities: Organizing as an Expression of Catholic Social Thought” brought together organizers, academics, and theologians to reexamine the role of organizing in the church.

Out of the conference came the Collaborative for Catholic Organizing, a new group that aims to build a stronger formation in organizing for Catholics as well as a clearly stated theology of community organizing, says Meg Olson, director of grassroots mobilization at NETWORK and co-coordinator of the Collaborative.

Will Rutt is the executive director of Intercommunity Peace & Justice Center (IPJC), an organization sponsored by 24 different Catholic religious communities based in Seattle, and another co-coordinator of the Collaborative. “Over the last 20 years, the infrastructure for justice work in the U.S. church has really been diminished,” Rutt says. “[The Collaborative] is an attempt to begin to reinforce support and rebuild that justice infrastructure in the church.”

Wood found that though Catholic parish participation in organizing has declined, leaders in faith-based organizing groups still tend to be very Catholic. The Collaborative is trying to “build up the toolkit” of organizing, Olson and Rutt say, by making sure the craft is taught and carried on and that Catholic organizers feel supported by their faith tradition and have a solid theology and sense of purpose in their faith to draw upon.

The power of relationships

Organizing is a craft, Hoo says, one that needs to be taught and passed on. It’s a process of engaging and empowering people who live near one another to work together on common issues and create change.

Community organizing differs from issue-based activism or advocacy because of its process of intentionally listening to members of the community, moving from their needs, and empowering them to be leaders, Hoo says.

Likewise, Rutt contrasts community organizing with other kinds of advocacy by pointing out that building and sustaining relationships is central to community organizing, as opposed to mobilizing around an issue and getting as many people on board as possible in a more transactional way.

One-to-one relational meetings are the “cornerstone of faith-based organizing,” says Finfer. These are 30- to 40-minute meetings where an organizer sits down with a person to hear their story and what concerns or motivates them. A group in a church, for example, would conduct these meetings with fellow parishioners. After the one-to-ones, there are house meetings, which bring congregations or parishes together to discuss issues and take action.

“Organizing is often something that people haven’t heard about before,” Hoo says. “We always try to teach out of people’s experience, we want to meet people where they are. As organizers, ultimately, we’re teachers. It’s not like we have some grand agenda we’re trying to enact across the United States. No, we’re teaching people these skills of public life that we think are really valuable.”

Hoo gives an example of community organizing in practice that occurred around 10 years ago, when Hoo was organizing in Los Angeles. He was part of a house meeting about health care at a largely immigrant parish. Organizers asked, “What do you do when you get sick?”

A lot of parishioners who didn’t have health insurance took off work and went to a local clinic as early as they could to get in line because the clinic did not give out appointments. As a result of the house meeting and listening to people speak, the parish ended up making a deal with the clinic that if they gave out appointments, the parish would help people keep them or call to reschedule.

“Before getting into health coverage and health care rights, it’s just like, ‘I want to have an appointment and not have to wait in line all day,’ ” Hoo says. “That’s human dignity, that’s something the church talks about. Eventually that led to getting Los Angeles to launch a program to provide coverage to undocumented immigrants. But that came after basic-level organizing that started with the question: What are the most essential issues that people have?”

“I have been doing a lot of one-to-one meetings,” Dao says. “This is what I love about community organizing—I get to listen to God’s people, to their joy, their pain, and their struggle and encourage them to work together to change the system. Right now, we are collaborating with other organizations to address child care and have a campaign so the state of Illinois can hear our story and provide affordable day care for all and raise the wages of child-care workers.”

Ortencia Ramirez, a member of OneLA (a local IAF group) started organizing in her parish because “all my life, I saw the struggles in my community,” she says. One day at church, a man who was involved in organizing made an announcement that resonated with Ramirez: “He said, ‘I wanted to make a difference, I just didn’t know how. I knew in my faith that I should be doing more for our community, but I didn’t know where to start.’ ”

Ramirez has been organizing for close to 20 years. “What’s kept me interested after all these years in organizing is the difference that I see that it makes in our community in L.A. County. I see the fruits of our labor,” she says. “The leadership training has helped me listen to people and take their issues on. It’s made me more of a public person because I’m very shy. Without my faith, I wouldn’t be doing community organizing.”

A democratic voice

“There will either be organized people or organized money,” says Frank Cloherty, a diocesan priest in the Boston area who’s been a community organizer for 62 years. “People must be educated to know that they have power.”

In 2023, studies from People’s Action Institute and the Kairos Center found that relational, power-based community organizing is an antidote to authoritarianism and a corporate-controlled economy in the United States. To face rising inequality, climate catastrophe, militarization of borders, and other injustices, the United States needs an “organizing revival,” the People’s Action study says.

Pope Francis warns against authoritarianism and capitalist corporations in both Laudato Si’ (On Care for Our Common Home) and Laudate Deum (On the Climate Crisis). “I reiterate that ‘unless citizens control political power—national, regional and municipal—it will not be possible to control damage to the environment,’ ” he writes in the latter.

The passing of Citizens United v. FEC in 2010, which ruled that corporations are people, the fact that parts of the 1965 Voting Rights Act have been gutted the past several years, and the fact that the top five richest people in the United States hold trillions of dollars of wealth are examples of how fragile our democracy is, Olson says.

“When the IAF got started in 1940, that was a response to the rise of fascism,” Hoo says. “Jacques Maritain and others who helped shape the IAF were responding to the rise of fascism. Looking around the world, we are there today. That’s a challenge, but I think our organizing work is an answer to that.”

In other parts of the world, community organizing grounds the work of the Catholic Church, especially in Latin America, Olson says. Joseph Tomás McKellar, the executive director of PICO California, a faith-based community organizing group, has taken part in several of the World Meeting of Popular Movements convened by Pope Francis in Bolivia, California, and Rome, where he’s met organizers from around the world.

“Organizing in other countries, compared to the United States, is light-years ahead,” McKellar says. “In this country we are more materially resource-rich, and that has enhanced our ability to build robust community organizations and make life better for those most excluded and oppressed. On the other side of the coin, some of the money that we have available to us has caused us to over-professionalize the craft of organizing and reduce incentives to take risks.”

McKellar continues on to say that in other parts of the world, the lack of material resources means that people are more committed to organizing “not because it’s a job, but because it’s about survival and their lives,” he says. “If our organizing in the States can tap into some of that spirit, we very well might get further than we seem to be getting now.”

Women play a significant role in organizing, both around the world and in the United States, where women make up the majority of community organizers in the church. Community organizing is strongest in countries that “aren’t known for strong democracy, or where democracy has struggled,” Wood says. “As you know, one can’t take democracy for granted in the United States anymore. So there is a shared reality there of how organizing responds to authoritarianism and how it can drive a democratic voice.”

Faith-based organizing and labor unions tend to be the most multiracial spaces in America, Wood says. Over the years, he has observed white Catholics falling away from organizing work. Organizers in CCHD’s synod report said it’s difficult to build solidarity across race and class lines, with one respondent saying the church in the United States is more concerned with “meeting a white middle-class standard” than serving and working with the poor.

Olson says this moment offers a real opportunity “for white and middle- to upper-class Catholics who want to live out Catholic social teaching” to support and get involved in community organizing.

A next step for the Collaborative, according to their synodal synthesis, will be having conversations with the USCCB and other Catholic institutions about what a renewed commitment to organizing could look like and how organizers can partner more fully with parishes and dioceses. A start to this, Olson says, is clearly articulating how organizing relates to the church’s mission.

A theology of organizing

“Like me, Pope Francis seems to love being around organizers,” says Erin Brigham, a theologian at the University of San Francisco who studies community organizing and Catholic social thought. “[Francis is] always making space to listen to organizers; he prioritizes meeting with them.” Brigham is part of the Collaborative and is cowriting a book about what a theology of community organizing might look like.

In 2019, McKellar, the executive director of PICO California, had a one-to-one meeting with Pope Francis. He gave the pope a photo of a fresco painting at Dolores Mission Church in Los Angeles that depicts Mary and Jesus as migrants.

“I asked him in Spanish, ‘Father Jorge, what words of ánimo, of encouragement, can you share with me that I can share with others in the United States who are accompanying those on the margins, fighting for justice and peace?’ ” McKellar says. “I continued on and he just stopped me, put his two fingers on my chest and said ‘Quédate con el pueblo,’ which translates to: Stay with the people, stay close to the people. Then he said, ‘and listen deeply to what the people are yearning for, and allow them to teach you.’ ”

This echoes the aim of the church’s Synod on Synodality, during which the institutional church is trying to listen to the people to help it realize its mission in the 21st century.

“What organizing really does is hold synodality accountable,” Rutt says. “The Spirit is moving and we’re seeing different desires and needs of the community. That’s great, but we’ve got to figure out how to actualize those.”

The model of synodality has been in “CCHD’s DNA” long before Pope Francis called for the Synod, McCloud, the executive director of CCHD, says, because “we go to the margins to listen to people—that’s what we were founded for. In many cases, [the folks we listen to] are not going to show up in our cathedrals, and oftentimes they don’t speak the language, so by definition they are not in the ‘in-crowd’ of what the Catholic Church is.”

Catholics experience the church to be a “hierarchical structured institution—the ideas and practices are shaped from top-down,” Brigham says. Even outside the church, “we’re so used to thinking within these power structures that the folks who make the decisions that impact my life come from top-down, whether that’s financial or political. Organizing is saying: Power also happens when we come together. We can live in a way that’s not just hierarchical or removed from personal experience.”

Resistance to organizing, Rutt says, is that some perceive it as ideological—“just progressives or conservatives mobilizing into a specific issue or category.” If synodality is truly implemented, “the ideological risk gets dissipated significantly,” he says. “Which is also the principle of subsidiarity, assuring that we’re moving from the community, not a predisposed ideology.”

Subsidiarity is a tenet of Catholic social teaching that says local groups have the greatest understanding of what they need and what is best for their own communities. The agenda emerges from the people.

One day, Finfer, the community organizer at the Massachusetts Communities Action Network, was reading Nehemiah and his eyes strayed to chapter five, where people are crying out because of oppression from usury and predatory lending. Nehemiah “calls a community meeting about it, and it forces the usurers to sign an agreement saying they won’t do that,” Finfer says. “Call it a meeting on predatory lending that happened 2,500 years ago.”

A theology of community organizing is going to be relational, attentive to the Spirit, and rooted in lived experience and encounter, Brigham says.

“As someone organizing, you need to be so deeply rooted in your values,” Olson says. “I’m thinking of this one guy, a pipefitter. He was like, ‘I go to Mass every Sunday and I’m active in my parish, and I work for the pipefitters union,’ but he couldn’t make that connection between [his faith and labor organizing]. It’s not his fault, it’s a fault of the church because no one ever articulated subsidiarity, solidarity, building power, and making social change as essential to our faith.”

For Dao, her theology is “grounded in the historical Jesus,” she says. “His time was similar to our time; there was so much oppression with the Roman Empire. In our time now, oppression is everywhere.”

Some see Jesus as a community organizer, Hoo says. Organizing over the years has been an “encounter with God, it changed my life. Through this work I decided to get baptized and become Catholic,” he says. “That’s the heart of what organizing is about—how people are transformed.”

“Jesus did not turn his back on people,” Ramirez at OneLA says. “You don’t let go and you don’t stop trying.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the Collaborative for Catholic Organizing is funded by CCHD. It is not, and the article has been updated.

This article also appears in the May 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 5, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

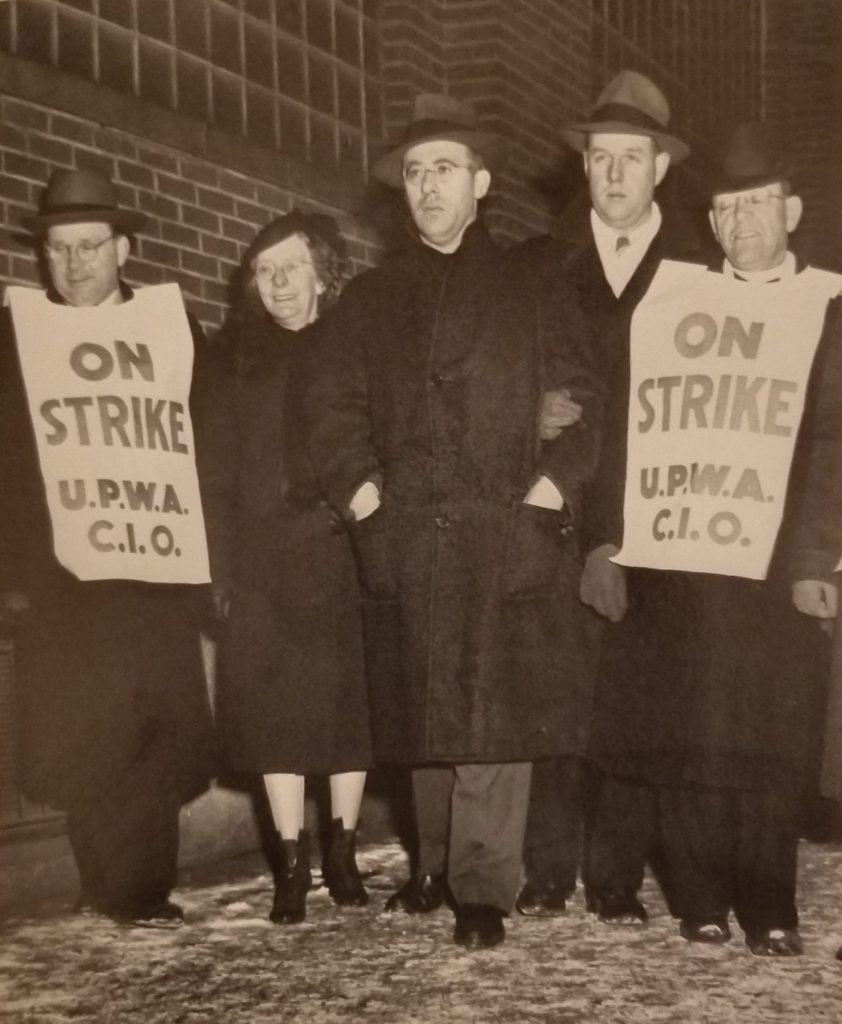

Header image: Pope Francis meets with West/Southwest IAF organizers in 2022. Robert Hoo, who stands in the middle of the top image, was one of the delegates. Courtesy Rabbi John Linder.

Add comment