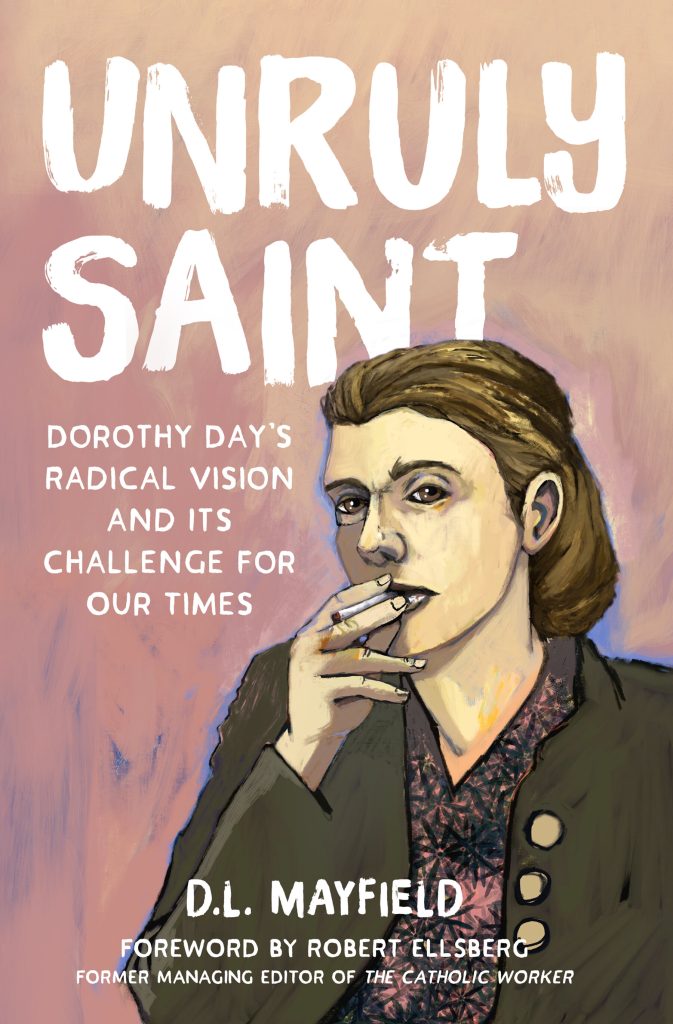

Unruly Saint: Dorothy Day’s Radical Vision and Its Challenge for Our Times

By D.L. Mayfield (Broadleaf Books, 2022)

People who write and speak about Dorothy Day, cofounder of the Catholic Worker Movement who died in 1980 and whose cause for canonization is now being considered by the Vatican, often draw very different or even opposing conclusions. Inevitably, anyone invoking Day in a public forum can’t help but reveal something of themselves.

Unruly Saint (Broadleaf Books), a new book by D. L. Mayfield, is refreshingly transparent. It’s not a book about Day per se but rather about Mayfield’s “personal engagement with the life of Dorothy Day in the years surrounding the birth of the Catholic Worker movement.” She comes to this book, she writes, “as a mother, a daughter, a sometimes activist, an anxious neighbor and a very lonely and religious soul.” Mayfield doesn’t claim that she wrote a biography. “I love her very much,” she admits, relinquishing from the start any claim of a biographer’s requisite objectivity. “Writing a book is hard, because you are ‘giving yourself away,’ ” Day writes in her autobiography, The Long Loneliness (Harper & Brothers). “But if you love, you want to give yourself.” In Unruly Saint, Mayfield gives herself away and hers is a better and more honest take on Day for that.

Mayfield recognizes a truth that hagiographers often miss. “Conversion narratives,” she writes, “have a pattern to be followed: a life of chaos and sin before conversion and then a beautiful life of faith and trust with God after. A distinct and clear line that separates the ‘before’ person and the ‘after’ convert. But the truth of conversion, Dorothy knew, is that it is a lifelong process and that it never fully ends.” Diverging from the standard before and after narrative, Mayfield quotes Day herself, who recounts her own conversion as the process of coming to “accept the faith that I believe was always in my heart” in her book From Union Square to Rome (Preservation of the Faith Press).

The “unruly saint” that Mayfield celebrates is hard to swallow for some who champion Day’s cause for canonization. Some try to rein her in to be the “ruly” saint they would have her be. Cardinal John O’Connor, the former archbishop of New York who started the canonization ball rolling in 1997, admits in a 2000 Catholic New York column that “Dorothy Day often seemed friendly to political groups hostile to the Church, for example, communists, socialists, and anarchists.” But to understand Day, he insists, “it is necessary to divide her political stances in two spheres: pre- and post-conversion.” More recently, on the conservative Catholic Answers Focus in August 2021, theologian Larry Chapp likewise “defends” Day from such sordid associations, “once she became Catholic, she completely disavowed her relationships that she had with Marxists and she opposed socialism.”

Unruly Saint is primarily, I think, a book about conversion, Day’s first, of course, but Mayfield’s just as much. Generations and eras apart and beginning from very different places, the conversions of these two women converge, so to speak, “in the thick of a personal crisis moment.”

Day was not brought up in any church and was not formally religious as a young woman. Mayfield describes Day’s conversion as started by “radicals who loved the poor who pushed her toward God—eventually to the point where she had to break ranks with them and enter the Catholic Church.” Day herself muses in From Union Square to Rome, “Better let it be said that I found [Christ] through His poor, and in a moment of joy I turned to Him. I have said, sometimes flippantly, that the mass of bourgeois smug Christians who denied Christ in His poor made me turn to Communism, and that it was the Communists and working with them that made me turn to God”

Mayfield, on the other hand, writes that she “had been raised in the white Evangelical Church in the United States [and] had tried hard to be a good Christian.” Like Day, though, Mayfield’s real encounter with Christ was not in the church. When she tried to evangelize her neighbors, newly arrived refugees from Somalia (“like any good missionary would”), she converted no one except perhaps herself. “I didn’t bring Christ anywhere,” Mayfield admits. “Instead I found him everywhere in cockroach-infested apartments on the very outer edge of my city.”

“I was being invited to sit down on couches and eat meals cooked over a stove for hours on end, invited to experience the face of Christ in the apartments of friends who had been resettled from far-flung and war-torn countries,” she continues. “I met Jesus in their handshakes, hugs, and kisses on my cheek; in the apartment doors left open a crack for me to come in and sit down; the meals of rice and beans and curry and stew; the waving of a hand to sit down and watch a grainy VHS of a wedding of a distant relative in Texas or Tanzania or Afghanistan.”

Many years before, Day also recognized the face of Christ in those who do not believe in him, quoting the French novelist François Mauriac, “There are all those who will discover that their neighbor is Jesus himself, although they belong to the mass of those who do not know Christ or who have forgotten Him. . . . For Jesus is disguised and masked in the midst of men, hidden among the poor, among the sick, among prisoners, among strangers.” In 1974, six years before her death, in On Pilgrimage Day describes a meeting with young anarchists with true affection: “Because I have been behind bars in police stations, houses of detention, jails and prison farms, whatsoever they are called, eleven times, and have refused to pay Federal income taxes and have never voted, they accept me as an anarchist. And I in turn, can see Christ in them even though they deny Him, because they are giving themselves to working for a better social order for the wretched of the earth.”

While Mayfield did not set out to write a biography, she is a careful writer. Her relatively brief account of Day’s history is among the most reliable. If most of her book focuses on the “life of Dorothy Day in the years surrounding the birth of the Catholic Worker movement,” it reflects, I believe, on Mayfield’s stated “personal engagement” with Day. Mayfield is a woman at roughly the same stage of life as Day was in those formative years of the Catholic Worker and, like Day, a mother. If these are the particular years of her personal engagement, Mayfield can also speak to earlier and later phases of Day’s life. Mayfield recognizes that while the world “looks different than it did in the 1930s, Dorothy Day’s radical vision is relevant today,” even as “new questions continue to be asked of both the movement and the people it seeks to serve as we enter into new eras.”

Mayfield is comfortable recognizing Day as a saint. Yet, as a non-Catholic, she does not overconcern herself with the question of the canonical process of the institutional establishment. Whether one thinks that Day’s canonization would be helpful or not, some forces have put her in a box and replaced her with a pious and tamed likeness. The rule-obsessed, nitpicky “St. Dorothy”—who preferred the old liturgical rites to the new, who abandoned her radical friends when she joined the church, who would obediently shut down the Catholic Worker if her bishop ordered her to—did not exist and has nothing to offer the present generation. Day who lived in history, on the other hand—who went to jail with striking workers, who resisted segregation, who called young men to “fill the jails” rather than fight in Vietnam, who demanded the overthrow of capitalism, and who counseled “one must live in a state of permanent dissatisfaction with the Church”—is a prophet for our time.

“God knows I need an unruly saint to journey with in these trying times,” writes Mayfield. God knows that an unruly saint like Day is what the church and the world need in this most perilous time in human history.

Add comment