Twice a week I hopped out of a taxicab between the Coptic Christian church and the blue-domed mosque in a neighborhood called al-Abdali. From there, I walked down the steep hill to Zawiya Street and through a courtyard where pink majnooneh flowers cascade over a tan retaining wall. I lived in Amman, Jordan at the time, conducting research on Muslim-Christian relations, and this was the route to the home of my Arabic language tutor, Akram.

One day, I asked Akram—who had fled Syria for Jordan six years earlier—if we could suspend our usual lessons on verbs and vocabulary to discuss the life of a Catholic priest. Father Frans van der Lugt, a Jesuit from the Netherlands, had been killed days before in Syria. I had never heard of Father Frans until after his murder and was embarrassed that I—someone dedicated to improving Muslim-Christian relations back home in the United States—had been ignorant about him and his efforts to foster interreligious coexistence in Syria.

Before his murder in Homs, a war-torn city less than 200 miles away from Amman, Frans had lived and ministered in Syria for nearly 50 years. He considered Syria his home and refused to flee when the civil war came and left Homs destroyed and its population starving. He was 75 when a masked man shot him in the head in the garden of the Jesuit residence on April 7, 2014.

To learn more about Frans’ life and legacy, Akram and I watched and translated videos that Father Frans had recorded in Arabic before he died. In these YouTube clips and by his life, Father Frans communicated two lessons on how to build the kingdom of God: the necessity of radical hospitality and the power of persistent hope in the face of suffering.

Many might wonder how God’s kingdom could be built in a city devastated by war and among a majority-Muslim population. But as Jesus says in the Gospel of Luke, the kingdom of God is not simply a place we can see or that we reach at the end of time. Rather it is something that can be built “among us” (Luke 17:20–21) and, as the theologian Origen said, “in our heart.” This is a truth that Father Frans’ life and legacy made known to me.

In the first video clip Akram and I watched, Frans sits in a basalt stone courtyard, talking about why he loves the Syrian people. Even as bombs echo in the background, Frans continues to speak cheerfully about the “spirit of mushaaraka” he witnesses in the Syrian people. He loves them, he says, because of their generosity, hospitality, and the way they sacrifice their own needs to welcome and help others.

This mushaaraka—which can be translated as “sharing” or “communion”—is something Frans also embodied. A trained psychotherapist, he founded al-Ard, (which means “the Land”) a center in the countryside that brought together able-bodied and disabled Syrians to till the land and grow closer to God. In Homs, he and the other Jesuits ran a bread-baking operation to feed the poor. Known as Abouna, or “our Father” in Arabic, Frans was a proponent of Zen meditation, led an annual eight-day hike for young people, and put on theater productions. Abouna Frans was a tireless servant, and his activities served everyone, Christian and Muslim alike.

Watching these videos, I learned from Frans what radical inclusion and reciprocal loving look like. Even in death Frans brought diverse people together. After he died, Muslim clergy and ordinary residents visited his grave in the Jesuit residence, offering prayers and flowers, and many Muslims attended Mass on the first anniversary of his death in 2015.

Father Frans possessed a deep faith in Jesus and in the resurrection that left him positive and cheerful up to the moment of his assassination. In the videos Frans filmed during the siege of Homs, when he and the others remaining in the Old City were nearly starving, he remained upbeat and able to rejoice in the beauty that still bloomed in the garden of the Jesuit residence.

One day, when Akram and I were talking about Father Frans and the suffering experienced by the people of Homs, he related to me an Arabic proverb that is also the name of a famous Syrian song: Lissa ad-dunia bi-kheir, which means, “Still, the world is good.”

For me, this Syrian proverb speaks of the trust in God and hope in humanity that Abouna Frans carried in life and held onto as he approached his death. Friends and witnesses to his murder say that when the masked man came to the Jesuit residence, Frans greeted him with peace, called him “brother,” and didn’t seek to resist or run when it became clear the gunman would shoot him.

Frans’ story is a reminder to me that the kingdom of God is not just something that comes at the end of all life. Rather it is something we can build on earth, even in the midst of suffering. Abouna Frans, who had faith that the resurrection and life would win out, constructed that kingdom on the rubble and damaged dreams of his Syrian family in Homs. He couldn’t take away the suffering, but he was with the people in it, just as Jesus was.

Abouna Frans’ willing sacrifice for all people—regardless of their faith, nationality, or views—challenges me to open my arms wider to others. His courage motivates me in my own vocation to break down prejudice here in the United States. His framed image above my desk inspires me to build the kind of Muslim-Christian coexistence that he fostered in Syria and that I witnessed in Amman’s al-Abdali neighborhood, where the sound of church bells and the Muslim call to prayer blend together.

Frans’ story compels all of us to build God’s kingdom courageously in a time when we may be tempted to treat our Muslim neighbors with suspicion or close our doors to refugees, many of whom come from the place Frans called home. Rather than responding out of fear, we are called to adopt Frans’ self-giving spirit of mushaaraka and step forward into the darkness with confidence that “still, the world is good.”

This article also appears in the November 2016 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 81, No. 11, pages 45–46).

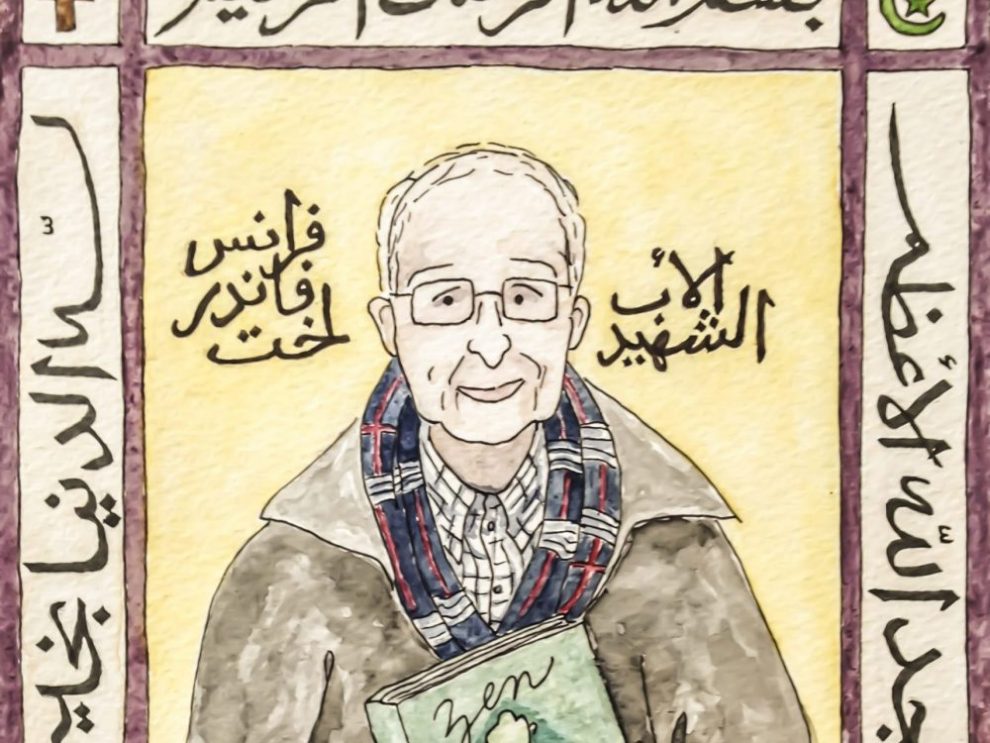

Image: Icon of Father Frans by Jordan Denari

Add comment