I was a senior in college when Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska album came out. This is the album that inspired the 2025 biographical film Deliver Me from Nowhere, which tells the story of the musician’s struggles while he was writing and recording the songs on this 1982 solo record, all of which are striking for their difference from other mainstream fare of the time, as well as from his previous music: There is no electric guitar, drums, keyboards, or saxophone.

The songs are dark, acoustic, folkish explorations of people living in a bleak landscape of crime, violence, murder, and malaise. In “Atlantic City,” a couple who’d moved to the rundown “America’s Playground” to rekindle their prospects and relationship resort to doing a “little favor” for a guy in the mob-ridden town. “State Trooper,” meanwhile, is from the perspective of an apparently psychotic late-night driver.

Springsteen often explains why his corrupt, violent characters do what they do without justifying their actions, but with crisp, sympathetic understanding that mirrors the divine compassionate justice I hope we’ll all receive someday. In this way, Springsteen helps me better imagine Jesus. The latter similarly has compassion—for the downtrodden, to be sure, but also for the morally and spiritually, if not materially, destitute.

“I’d love to hear your story”

The last song on the album, “Reason to Believe,” offers little reprieve from the grimness of the album, nor an easy reason to believe in God, tomorrow, or humanity. Yet it finds evidence of belief among people enduring heartbreak. I think it became my favorite song on the record because it acknowledges that belief exists and is not absurd. This, no matter what the narrator—or the songwriter, who was soon to sink into depression—may have believed, made the song different from almost all the popular music I’d heard before, and it resonated with my own inchoate faith.

I was hardly the only one to see a kind of hope in “Reason to Believe,” but many disagreed, including the Boss himself, who called it a “common misinterpretation” to see it as a “hopeful song.” However, as Springsteen acknowledged that misunderstandings of his hit “Born in the U.S.A.” helped make him a superstar, I trust he’ll tolerate other interpretations of “Reason to Believe.”

Since then, I’ve seen more hope motifs in Springsteen’s music—not to mention more evidence of belief. With echoes of the story of the Samaritan woman (John 4:4–52) who met Jesus then told her townsfolk about the “man who told me everything I have done,” Springsteen seems able to say all we need to know about a character in four minutes, including those who’ve hurt others. Within the first few lines of “State Trooper,” the narrator declares that he has a clear conscience about the things he’s done. His menacing monotone suggests he should have anything but. That’s especially true as he threatens the imagined state trooper he fears will stop him, speculating that maybe the trooper has kids or a pretty wife. This is a damaged man, not to be messed with.

While I was writing this, I saw a scene in The Chosen TV series in which Jesus sits beside a future disciple and says, “I’d love to hear your story.” As Springsteen tells people’s stories, I imagine he’s presenting a character’s case, like a defense attorney, an apt image given Nebraska’s often criminal milieu. His frequent direct address use of “sir” on the album implies he’s addressing an authority, perhaps a judge hearing a confession or alibi. While Springsteen probably doesn’t believe all his characters deserve a break, there’s something charitable in finding their story worth sharing with us.

A meanness in this world

Some of the lyrics are inspired by the stories of Catholic fiction writer Flannery O’Connor. The title song, “Nebraska,” is written in the voice of unrepentant 1950s serial killer Charles Starkweather. “There’s just a meanness in this world,” Starkweather says, echoing the “Misfit” character from Flannery O’Connor’s “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” Jesus, if he were listening, might not find this explanation exculpatory, but it’s the mitigating reality of a fallen world. Although the word is never repeated, meanness is an overriding theme of the record: a cause and result of much of the sin and crime it presents.

In two songs without explicit crime, the narrators’ childhood memories convey a sense of social stratification that colors perspectives and influences choices. The occupants of the “Mansion on the Hill” enjoy “music playing” and “people laughing all the time,” all behind steel fencing, safe from the denizens of the “factories and the fields” below. The narrator remembers how he and his father would “park on a back road” to “look up” at the mansion, implicitly measuring the distance. In “Used Cars,” another boy rides with his family to test drive a used car. When neighbors come to see “our brand-new used car,” the narrator, looking back, wishes they would “kiss our asses goodbye.”

Debts no honest man can pay

“Highway Patrolman” and “Johnny 99” depict the criminal consequences of meanness produced by economic and political factors beyond one’s control. The patrolman—a farmer until “wheat prices kept on droppin’ ”—tries to restrain the criminal violence of his “no good” brother Franky. When Franky seriously injures a man, the patrolman lets him escape. He does this because Franky is his brother, but also because they have no options after losing the farm and what the Vietnam War did to Franky. Johnny 99, laid off when the auto plant closed, looked for a job but “couldn’t find none.” Despondent and drunk, he shot a night clerk then explained to the judge the bank was taking his house. He has debts, he says, “that no honest man can pay”—another nod at O’Connor. While Johnny doesn’t argue for his innocence, he does say it was “more than all this” that drove him to it. More than all this may be a synonym for meanness.

The title song is the darkest. Just seconds in, the coldhearted killer reports taking his young girlfriend on a murder spree. As he smugly shrugs off what happened, his recognition of the victims’ innocence is belied by his lack of regret. That disregard is more pronounced when he tells the sheriff that when they electrocute him, he wants them to make sure his girlfriend is with him, “sitting right there on my lap.”

“Nebraska” doesn’t identify the forces that drive the serial killer, the meanness in his life, but maybe there’s a hint when he proclaims that, though he can’t feel sorry for the things he did, for a while they “had us some fun.” This is a bad man, and Bruce doesn’t mince words—they are the killer’s own words—but the “fun” comment is also pitiful evidence of an empty, sociopathic life that no one voluntarily chooses. No jury would accept this excuse—if that’s even what this killer seeks. Nothing he says seems meant to absolve himself—which may be the first step to remorse: he admits he’s not innocent.

Deliver me from nowhere

Similarly, the “State Trooper” driver indicates he knows he’s in trouble. If there’s someone out there, he prays that they will hear his last prayer and “deliver me from nowhere.” These words lend the title to the recent film, but they also show up in the more lighthearted “Open All Night,” also on Nebraska. Nearly the inverse of “Trooper,” “Open’s” hero is also driving to his baby, but unlike in the other song, he drives into daylight at the end. Their nowheres are in very different places.

After the narrator of “Nebraska” is convicted and sentenced, he explains that the judge and jury found him “unfit to live.” And if they want to know why he did what he did, his explanation is that “meanness in this world.” His emotionless recitation suggests he’s already in a heartless, soulless void, but how could such a situation be entirely of his own will? The killer is a part of the meanness, contributing to it more than most. But he must have experienced his share in his life.

The characters in these and other Nebraska songs merit little or no mercy in human judgment, which often demands vengeful satisfaction. Few seriously argue with this reality, probably including Springsteen himself. I don’t claim higher ground either. After all, justice absent punishment may risk future crime and injury.

A kingdom of love to be gained

However it works, though, I hope Jesus presents our cases at the end, not human officers of the court. Those lawyers and judges—like all of us—don’t think like Jesus, a concept Matthew (16:13–23) presents in a few stunning paragraphs. When Peter proclaims that Jesus is the son of God, Jesus praises him. After Jesus subsequently declares he will be killed and rise again, however, Peter protests: “No such thing will ever happen to you.” Scolding, Jesus calls him Satan for “thinking not as God does, but as human beings do.”

Clearly, no human thinks as God does, which leads me to Jesus’ parable of the generous landowner (Matt. 20:1–16), who pays all he hired equally, no matter when they started work. Responding to earlier hired people’s complaints (who exhibit very human thinking), he says, “My friend, I am not cheating you. Did you not agree with me for the usual daily wage? . . . What if I wish to give this last one the same as you? Am I not free to do as I wish with my own money? Are you envious because I am generous?” By definition, the hero of Jesus’ parable about the kingdom thinks as God does—that is, he is God, who is most generous with mercy.

As I imagine Springsteen presenting his characters’ cases, I envision Jesus charitably understanding us—major flaws, minor foibles, motivations we do not fully understand or control—and making our case. Where Springsteen tells stories that hint at the roots and causes of abhorrent behavior, Jesus sees all thoroughly and with compassion, knowing what is or isn’t within one’s ability to change, what someone is morally culpable for. He perceives when good versus evil is clear-cut for us, and when we’re incapable of knowing, when sin helps gain an unfair advantage or when it makes ends meet, pays bills, or feeds a family. Our world is designed to create inequities, but Jesus—like the generous landowner—offers mercy.

Returning to “Reason to Believe,” and belief, in his autobiography, Born to Run, Springsteen connects his work to Catholicism: “I tried to meet its challenge for the very reasons that there are souls to lose and a kingdom of love to be gained.” Maybe it’s not surprising he described his career as “my long and noisy prayer.” I am not such a fan that Springsteen supplants Jesus for me, but in this sense of mission—ministry?—and the sympathetic insight of his music, I see Jesus better through his work.

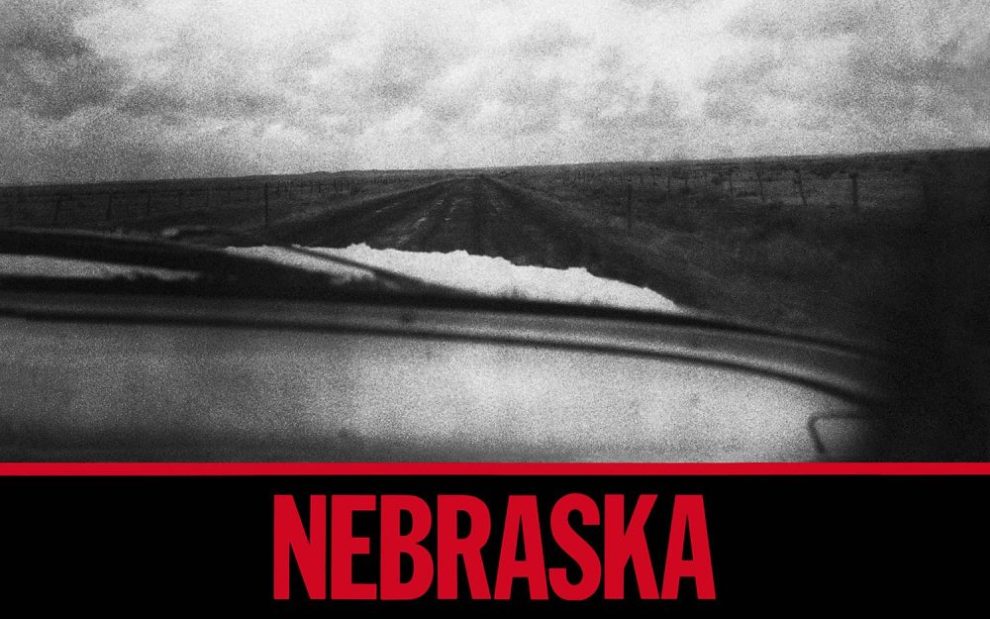

Image: Nebraska album cover, Bruce Springsteen

Add comment