On Chicago’s far south side in the early 1930s, as the Great Depression was hitting the many steel mill laborers in his parish, Father James Tort started receiving letters and petitions addressed to St. Jude. People sent the letters to the National Shrine of St. Jude, which Tort had just founded at Our Lady of Guadalupe parish. The letters flooded in—a sign people were clinging to faith in a time that felt hopeless.

Tort, a Spanish-born Claretian priest, decided to publish these letters to spread devotion to St. Jude. Following the founder of his congregation, Anthony Mary Claret, who was called the “modern apostle of the good press,” Tort started a publication called The Voice of St. Jude in 1935 to “encourage, inspire, and equip ordinary Catholics to live their faith in everyday life.”

By the early 1940s, the magazine shifted from focusing solely on St. Jude devotion to educating St. Jude devotees about Catholic social teaching and public policy, covering issues like labor unions, housing, race, and war. By 1942, the magazine had around 30,000 subscriptions.

In 1949, Robert Burns—who would serve as executive editor of Claretian Publications until 1984—entered the Claretian offices in Chicago on his first day of the job. He found a staff of 11 laypeople publishing The Voice of St. Jude, struggling with a six-month backlog of mail from St. Jude patrons.

“Once I got to establishing a system of answering every letter received, I got hooked,” Burns was quoted as saying in a press release for his retirement. “It was a never-ending job, like painting the Brooklyn Bridge.”

In 1963, the Claretians renamed The Voice of St. Jude, and the magazine became U.S. Catholic, inspired by the Second Vatican Council’s call to engage every corner of Catholicism’s “big tent.” That early engagement with readers—responding to their concerns and publishing their words—is a legacy that has continued throughout U.S. Catholic’s history.

In the first issue of U.S. Catholic, Burns and the editors wrote that in the years leading up to the name change, they had been “pursuing with something like dogged determination” an editorial policy focused on interpretative reporting rather than “essays telling you how and what to think.” There were painfully few Catholic magazines that concentrated on “making the world we live in more intelligible,” they wrote, “allowing their readers to judge and evaluate for themselves.”

Rather than publishing articles about Vatican finances or bishops’ conferences, the editors wrote that U.S. Catholic would focus on “give-and-take discussions about the pain and promise of a changing church.” That focus remains central to the magazine’s identity today.

U.S. Catholic remains a ministry of the Claretians—a congregation of missionary priests and brothers—receiving funding and editorial oversight from them. In addition to continued coverage of economic, racial, and labor justice, in more recent decades U.S. Catholic has championed women’s rights and LGBTQ+ justice.

According to Burns in that same press release, U.S. Catholic “prefer[s] raising significant questions to supplying easy answers. As a consequence, we carry on a continuing dialogue with our readers.”

“Journalism 101”

Burns “wanted to establish sort of a Catholic New Yorker,” says Cathy O’Connell-Cahill, an editor of U.S. Catholic from 1979 to 2015. “He had very high standards: literary standards, visual standards, theology standards, and he was impatient with many Catholic publications of the time that he felt were overly pious and sermonizing or telling people what to think.”

O’Connell-Cahill says that for the Sounding Board section of the magazine, which was one of the most popular sections, the editors would send out surveys to around a thousand readers with a free return envelope. They would often get around a 30 percent return rate and would tally up the responses by hand and type up readers’ words to publish.

The most successful articles, O’Connell-Cahill says, would tap into concerns that were already on the minds of Catholics in the pews.

“One of my editorial slogans came from something one of my bosses once said about an article: ‘Would anybody turn off the TV to read this?’ ” O’Connell-Cahill says. “That was one of my guiding principles: If I found I was bored reading an article, chances are the reader was going to be way more bored than I was. I tried to cultivate my bored meter and my jargon meter. We always tried to stamp out church jargon.”

Tom McGrath, who was an editor from 1978 to 2001, similarly asked of articles: “Would I talk about this with my neighbors?” he says. “This is just journalism 101—but often not in the Catholic Church, where it’s top down, we’ll tell you what to think.”

U.S. Catholic would occasionally take articles “over the transom”—pieces people would send in that were unsolicited—but “90 percent were rejected,” O’Connell-Cahill says. Each issue of U.S. Catholic was “crafted by the editors to be covering what we wanted it to cover, not what the writers just happened to send in that month. So you’re steering the ship in a direction.”

They hired journalists, reporters, and photographers, many of whom worked for secular publications. “We hired top journalists as much as we could get them on with the money that we had,” O’Connell-Cahill says.

Burns had high standards for journalists. “He’d say, it sounds like before you even start the story, you know what you’re going to write,” O’Connell-Cahill says. “This is not what we’re doing. You need to have an open mind to go out and find out what people are really saying and not have it all in your head before you start.”

McGrath says he remembers Burns having lots of guidelines and guardrails for maintaining these high standards when editing and writing, such as a forbidden word list, which included the word ongoing. “He refused to let us use what he called the imperial we,’’ McGrath says. “Like, ‘we should all’ this or that. What we wanted was respect for everyone.”

Throughout the years, the Claretians published many other publications with the support of the U.S. Catholic staff. One of them was Context, started in 1974 by Martin E. Marty, a religion scholar at the University of Chicago. Others were Salt, for Christians seeking social justice; Bringing Religion Home, about teaching religion at home; Generation, directed to older Catholics; GooseCorn for high-school Catholics; and others. Some of these were absorbed into U.S. Catholic as columns—for example, Salt is now Salt & Light, and Bringing Religion Home is now Home Faith.

Claretian Father Mark Brummel, who was editor-in-chief of the magazine from 1972 to 2002, says U.S. Catholic is still a “Chicago-based magazine. You look at America, that’s New York. But we have a good emphasis on Chicago and the Chicago spirit. It’s a headquarters for us, and we were able to benefit from that.”

A lifelong education

In December 1967, the editors of U.S. Catholic wrote an editorial against the Vietnam War, one of the first Catholic publications to do so. “That really inspired me to want to come work there,” McGrath says. “I think [editor] Kevin Axe was probably very active in that decision. He was a Vietnam vet himself—came fresh from being in Vietnam to a job at U.S. Catholic.”

McGrath was recently out of seminary and didn’t have journalism experience, so the Claretians created a public relations job for him. McGrath went on to become executive editor. Throughout his career he felt that the Claretians really trusted laypeople, he says.

Brummel was the first editor to bring U.S. Catholic to the Associated Church Press, where they collaborated with other faith-based publications and received awards for their reporting. According to Brummel, they were the first Catholic publication to get involved in this ecumenical organization.

During the 1980s, Brummel and other Claretians were the first to start an official cause for Dorothy Day’s canonization. They published articles and ads furthering the cause in U.S. Catholic and other Claretian publications. “We got a lot of letters in response; it was tremendous,” Brummel says. “But then we found out that the only way to move this thing forward was to go to New York, and then the bishop there took it up. So it’s still in process, and we’ve been given credit for that over time.”

For many years, starting in the 1970s, the editors gave out a U.S. Catholic Award to someone who furthered the cause of women in the church. Those awards were one of Brummel’s passions—Dorothy Day was the first person they offered that award to, though, characteristic of Day, she politely declined the recognition.

“Burns had a great hope that things were going to change in the church,” O’Connell-Cahill says. “I remember him at a Catholic Press convention. The bishops were going to do a pastoral letter on women. Burns got up and he said, ‘There’s going to be women priests. It may not be in my lifetime, but you listen to me. We just have to wait.’ ”

In those days, for Expert Witness interviews, O’Connell-Cahill says the magazine would fly people out to Chicago for a day to be interviewed at the office. The entire staff would join, and they would talk back and forth for hours, sometimes the whole day.

“What this allowed us to do was to get way beyond the surface,” she says. “We’d have scripture scholars and theologians, or we’d have politicians and activists, not just from the Catholic world. I look back on the job and think that was a lifelong education with people. I have never forgotten some of the stuff they’ve said.” Some of those interviewees included Elie Wiesel, Elizabeth Johnson, Walter Brueggemann, and Daniel Berrigan.

Writer Brian Doyle was working at U.S. Catholic when O’Connell-Cahill started in 1979. “We were fortunate to have him as one of the delightful, quirky voices that made U.S. Catholic what it was,” she says.

Daring moves

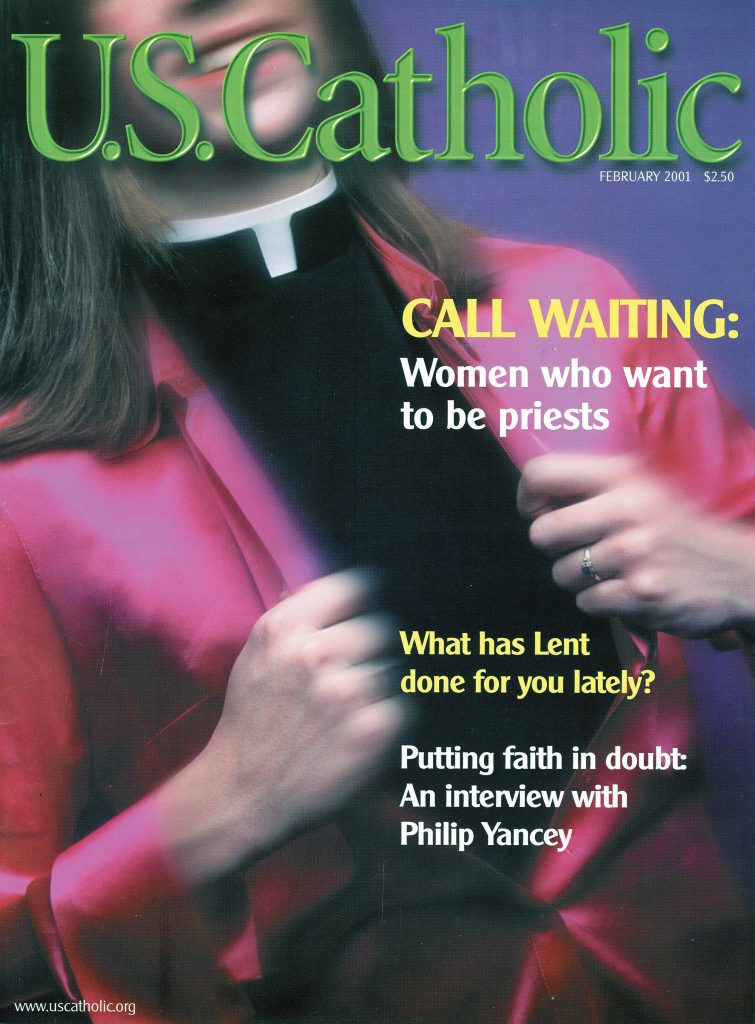

In 2001, U.S. Catholic’s reporting incited a Vatican investigation. On the cover of the February 2001 issue, art director Tom Wright took a photo of his daughter “pulling off a bright fuchsia blouse, and underneath it is a black shirt and collar,” Wright says. “Like a Superman in the phone booth kind of deal.” The title read “Call waiting.”

Heidi Schlumpf, a journalist who was an assistant editor at U.S. Catholic at the time, wrote the article that appeared on the cover, which highlighted the experiences of a handful of women who felt called to ordination. “It was during a time when a lot of Catholic organizations and publications were very reticent to talk about women’s ordination; Ordinatio Sacerdotalis (On Reserving Priestly Ordination to Men Alone) had come out,” she says. “But U.S. Catholic never shied away from tough issues or controversial conversations. Even though we were connected to a religious order, there was an extraordinary amount of editorial independence.”

Later that year, the Claretians received a letter from the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith saying they wanted them to retract the story. The Claretians hired a canon lawyer, and the head of the Claretians from Spain flew into Chicago for meetings.

“We wrote back and said we weren’t going to retract,” Schlumpf says. “Finally, they said that we should run the text of Ordinatio Sacerdotalis in the publication. So we ran it with a line saying that we were being forced to do so by the CDF. And we ran it in little tiny type.”

Schlumpf worked at U.S. Catholic from 1999 to 2008, before going on to work at the National Catholic Reporter, eventually serving as executive editor and, most recently, as senior correspondent.

“Sometimes I tell this story to people and they’re like, ‘That’s so cool, you got investigated by the Vatican,’ ” she says. “It really wasn’t that cool, because I felt so bad for the Claretians. They have this institutional connection to the church and they had to take this really seriously. But I felt supported by the Claretians during that whole controversy.”

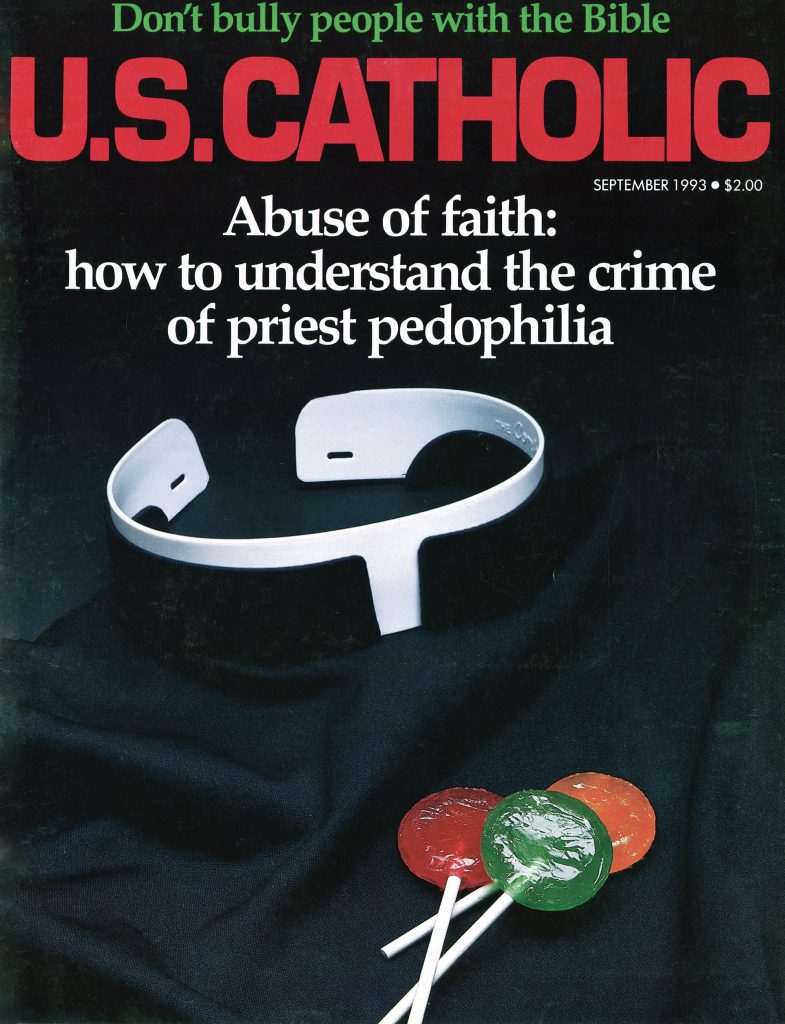

In 1993, U.S. Catholic ran a cover story on the clergy sexual abuse crisis “when we had our own crisis with priests here in Chicago,” O’Connell-Cahill says. “This was before the whole thing broke open with the Boston reporting. Not many Catholic publications were writing about that at the time, partly because it was easy to say, ‘Well, that’s just over there, that’s not happening here.’ ”

Wright, the art director, shot a cover photo that included a lollipop and a clerical collar. “It was risky,” McGrath says. “But I authorized it. Some of the Claretians expressed their disappointment with it.”

Wright started as art director of U.S. Catholic in 1985 and worked there for 25 years. His background was in advertising, and through his advertising jobs he met Glenn Heinlein, who was the previous art director at U.S. Catholic.

“Heinlein asked me if I could help him shoot U.S. Catholic covers because I was also a photographer,” Wright says. “This was back in the days of sending type out, getting galleys, cutting the galleys out, scotch-taping them down and then sending that off to the typesetter again.”

Heinlein tragically passed away at age 53. “I literally got the job offer at Glenn’s funeral,” Wright says.

Wright converted a bedroom in his home into a photography studio, where many of the covers were shot. He learned how to use a view camera (think of an old-fashioned photographer looking under a cloth), and he shot many of the covers with that camera.

“I’ve never been one to anguish over much of anything, but the U.S. Catholic covers—if I went away with one that was just OK, I was very depressed,” Wright says. “I think back at this, how nervous everybody must have been, because I wouldn’t come up with an idea or a photo until a day or two before the magazine had to go to the printer.”

His advertising background informed how Wright approached the art direction. Once in a meeting, he said, “Jesus is a product just like any other product. We’re marketing Jesus, Christianity, and social justice. It’s convincing people to buy an idea. It’s no different than selling tractors. Why do you need this tractor?”

“Democracy of ideas”

The art and title meetings were one of Wright’s favorite parts of the job. “It was an amazing democracy of ideas,” he says. “I am not a Catholic by any stretch. I think part of why I worked there so well was I was more of a resource.”

“[Wright] saved us so many times,” McGrath says. “He’d say, ‘Is anybody going to get this, our title?’ If somebody is not in the ‘in crowd,’ are they going to get it?’ ”

Like O’Connell-Cahill had her bored meter and jargon meter, Wright had his fun meter. “If it started getting not fun, that’s when I knew I was ready to move on,” he says. “The proof was always in the magazine when it came out: It worked or it didn’t work. Coming up with a really great cover idea made my week. I didn’t pay much attention to the publication awards.”

Schlumpf says the work environment at U.S. Catholic was a “truly collaborative approach, not top down,” she says. “It’s striking to look back and see how much we did.” Schlumpf points out that at least three former managing editors of U.S. Catholic have gone on to be ordained in the Episcopal Church, including Bryan Cones, Tara Dix, and Meghan Murphy-Gill. The staff were “really faithful people who loved the church, and their commitment to it in their own lives was so evident and also in the work they did,” she says.

Alice Camille, who has written the Testaments column for U.S. Catholic for over 20 years, is retiring this year. “U.S. Catholic is the only periodical I’m still writing for and that’s because it’s very hard to say goodbye,” she says.

Camille first read U.S. Catholic when she was a teenager. “My sister subscribed me for my birthday one year, which kind of pissed me off,” she says. “I sort of halfheartedly read it. And I remember thinking, even then, that the magazine was popular Catholicism. It was more for people like me, some teenager.” By the time she started writing for U.S. Catholic, it had become more social-justice oriented and seemed to take more risks, she says.

Camille has been a Catholic freelance writer for much of her career. In the first article she ever wrote for a Catholic publication, she mentioned a bishop’s name, and the editor “immediately called me and said, ‘Never mention bishops at all or you won’t have a career as a Catholic writer.’ ”

“For years, I was afraid to call the church on anything,” Camille says. “But we need a voice that will do that. We don’t need any more ‘yes’ people in the church. We need ‘no’ people, and we need ‘hey’ people. I’m anxious to see how U.S. Catholic continues to follow that bold trajectory.”

O’Connell-Cahill looks back on her years at U.S. Catholic and sees the editors’ and writers’ courageous and constant struggle to listen to readers and take direction from them.

As Burns wrote on that typewriter in 1963: “You will not find all the answers in U.S. CATHOLIC. It may even be that you will find precious few. But if you are willing to look you will find more often than not the stuff of which intelligent and mature judgements are made. We feel that you, our readers, are quite capable of making such judgements granted the opportunity to examine the world as Catholics encounter it.”

In these pages, through 90 years of the changing tyranny of governments, economies, wars, scandals, and more, everyday Catholics have examined life, wrestled with significant questions, and spoken of the pain and promise of church. Thoughtfully engaging what it means to live one’s faith is a never-ending job, like painting the Brooklyn Bridge—but it seems U.S. Catholic readers, writers, and editors are hooked, and they’re not going anywhere.

This article also appears in the June 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 5, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Header Image: Editorial staff, including Claretian Fathers James Maloney and Robert J. Leaver and Robert E. Burns, at a U.S. Catholic editorial meeting in the 1960s.

Add comment