In my early 20s, my faith life was in a rut. I attended Mass regularly but felt frustrated by elements of most Roman Catholic parishes I attended: rushed prayers, irrelevant homilies, and distracting folksy music. I participated—but perhaps not with my whole heart. I was attracted to the Latin Mass, which I appreciate for the solemnity and humility of the priest facing the altar, the sacred sound of Gregorian chant, and the dedication of the congregations devoted to it. These people took catechesis and Mass attendance seriously, actively participating with their missals and standing in long lines for confession. But it wasn’t until I attended a Melkite Greek Catholic church, with roots in the ancient Orthodox Church of Antioch, that I found traditions and devotions that grabbed at my heart as well as a new language with which to praise God.

When I first entered the Byzantine church for the Sunday divine liturgy, all my senses were immediately called to attention, and my attention was kept until the liturgy ended an hour and a half later. There was hardly a moment of silence. New to the traditions but little by little understanding their significance, I followed the lead of fellow parishioners.

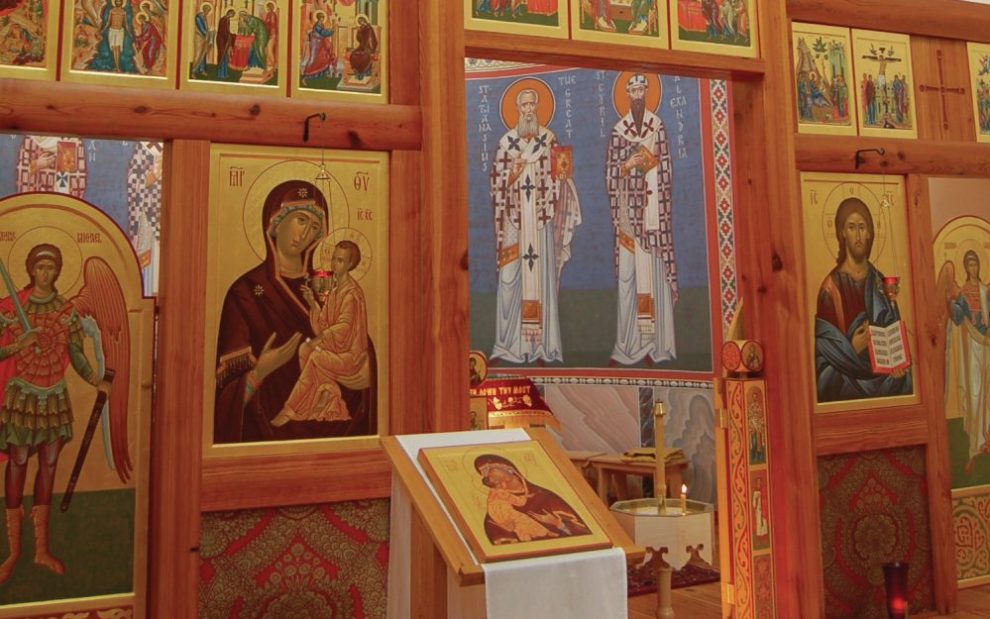

On my way into the nave, I lit a candle in the narthex before icons of Christ and the Virgin Mary Theotokos (Bearer of God), declaring my presence to God and bringing forth my special prayer intentions. The chanted psalms of the Orthros (Morning Prayer) drew me into the liturgy, along with the clanging of censers and wafting of incense as the deacons censed the whole church and congregation. My sight was filled with gold and colorful icons. Saints and angels surrounded me, and the dome above displayed Christ Pantokrator (All-Powerful) at its peak. Whereas traditional Western churches awe you with high ceilings and long naves, making you feel small and drawing your gaze upward and forward toward the altar, Eastern churches tend to be smaller, domed, and circular, making you feel surrounded by the Church Triumphant and part of the dome of the heavens and earth.

Many Byzantine churches don’t even have pews. People were moving about, praying before icons of their patron saints, greeting each other, and receiving the sacrament of reconciliation facing the iconostasis (the screen separating the altar from the congregation). The priest gave absolution while holding his stole over penitents’ heads. When the epistle and gospel were to be read, the deacon beseeched, “Let us be attentive!” At dozens of points during the liturgy, the faithful made the sign of the cross—whenever the names of the persons of the Trinity or the Theotokos were chanted, whenever a blessing was given by the priest, or simply whenever an individual felt strongly about a particular prayer intention.

I was struck by how the Catholic faithful in the Byzantine rite showed such reverence for the Eucharist. Many people didn’t go up for communion; it is considered essential to keep up with prescribed weekly Wednesday and Friday fasting and abstinence from animal products, to have examined your conscience, and to be in a state of grace. Everyone bowed and made the sign of the cross as each gift was processed toward the altar. These gifts themselves came from the sacrifice of the community. The bread was baked by a parishioner and marked with the special seal of the parish. All communicants shared from this same loaf. Chants of the choir and priest intensified up to the epiclesis when the Holy Spirit was called down upon the gifts. I was surprised that the Eucharist was leavened bread, which the priest dipped into the precious blood and placed on my tongue. In respect of the sacred mystery, many people washed down the Eucharist with blessed but unconsecrated bread to make sure every particle of Christ’s body and blood had been consumed worthily.

When I first received the body and blood of Christ in the Byzantine church, tears came to my eyes as the priest declared, “The servant of the Lord, Nigel, receives the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ for the remission of sins and life everlasting.” The priest’s declaration felt like a stark reminder of the power of the Eucharist to forgive sins and grant eternal life, which I had easily forgotten with the much simpler “The body of Christ” that is said in the West. Moreover, hearing my name felt like Christ himself calling me.

At the end of the liturgy, all in attendance were invited to take more of the blessed bread—antidoron (“instead of gifts”)—as a meal of fellowship and love and share it with loved ones who couldn’t come to church. This serves as a visible sign of the blessings of attending the eucharistic service and an invitation into the life of the church.

I pray that healing and reunification between our churches can be achieved.

Advertisement

The Roman Catholic Mass of my home parish will always be a place of deep connections, history, familiarity, and comfort, but I now find more affinity with the Byzantine rite. I feel at home with theological emphases of Eastern Christianity, not always developing strict formulas for how God acts through the sacraments but standing in awe before sacred mysteries.

A further emphasis of Eastern Christianity that resonates strongly with me is the Jesus Prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” It is so simple and yet so fundamental that I can say it as I breathe in and out, again and again. Where Roman Catholics have the rosary and its complex sequence of prayers and meditations, Byzantine Catholics have prayer ropes, with each knot inviting one to say another Jesus Prayer. For mystics of Eastern Christianity, the constant repetition of this prayer is the center of their meditative practice. For me, often distracted, anxious, or dwelling on the past, the accessibility and depth of the Jesus Prayer turn my heart toward continual renewal and greater trust in God.

Getting into the routine of attending a Byzantine parish, every Sunday I feel more deeply immersed in an ancient tradition in which I may spend my whole life trying to further participate. Most of my fellow Catholics won’t experience this expression of Christianity, but there are many ways to be Catholic. In finding the deeper essence of our church within a different expression of faith that Eastern Catholics share with Eastern Orthodox, I pray that healing and reunification between our churches can be achieved. There is room for diversity within a church with universality in its name. With two traditions nourishing my soul, I feel as I imagine St. Pope John Paul II did when he said, “The church must breathe with her two lungs!”

One direction

There were several splits over doctrine in the church that Jesus founded: the Great Schism of 1054, which separated Eastern Orthodox (the main church of Greece, Russia, and Eastern Europe) and Catholics, and the earlier schisms, which separated Oriental Orthodox (centered on Armenia, Ethiopia, Egypt, and the Levant) and the church of the East (that of Iraq, Iran, and India). Over the centuries, many groups within these churches have returned to communion with the Bishop of Rome, representing five distinct rites across 23 sui iuris (“of one’s own right”) churches of the Catholic Church, the biggest being the Ukrainian, Maronite, Melkite, and Syro-Malabar Churches. Roman Catholics can participate fully in the sacraments of any of these 23 churches. Progress has been made in the past century toward healing tensions between Rome and the Orthodox Churches, with mutual anathemas lifted and shared declarations of faith made.

This article also appears in the March 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 3, page 45-46). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Flickr.com/Andrew Gould

Add comment