When we tell someone “You’re a saint,” we are usually complimenting them on their ability to selflessly shoulder a relentless torrent of mundane tasks we would rather not do. Our saint is organizing the parish rummage sale, looking in on an elderly neighbor, driving the carpool, and caring for a sick dog.

“You’re a saint” is never followed by “because you’ve learned the beliefs you previously held did not reflect reality, and you changed your mind.” In addition to being a rather awkward compliment, it also does not reflect how we tend to think of saintliness. Saints tend to be the nicer-than-average people doing nicer-than-average things that can be neatly printed up on prayer cards and stuck to a car visor.

There are countless examples of “You’re a saint” saintliness in Óscar Romero’s life, many of which were highlighted as part of the case for his canonization. He traveled great distances along narrow and dangerous roads to say Mass and offer villagers the sacraments in remote parts of El Salvador. He arranged medical care for people who lacked the resources to get it themselves, especially the elderly. When he learned that migrant coffee harvesters often did not have places to sleep and were spending nights on the ground in the public square, Romero housed them in church buildings.

For most of his career, though, Romero not only failed to tie the suffering of the poor to larger issues of structural injustice and state violence, he also was openly critical when others in the church did.

In 1973, as editor of the Catholic newspaper Orientación, Romero harshly criticized changes at Externado San José, an elite Jesuit high school. The school’s offense? Opening a night school for poor students, sending its wealthy students on a field trip to witness desperate poverty as part of a sociology course, and publishing a magazine where some students questioned their parents’ values. Romero denounced the changes as “demagoguery and Marxism” and charged the school with offering “a false liberating education.”

Romero’s editorial sparked investigations of the school by both the church and the Salvadoran government. Both church and state ultimately concluded Externado San José had done nothing wrong, and Romero’s archbishop asked him to publish these findings in Orientación. Romero did—on the paper’s last page.

Romero had intense faith in hierarchy, authority, and tradition. In his criticism of Externado San José, Romero acknowledged the need for education reform in El Salvador, in particular to bring Catholic education in line with the teachings of the Second Vatican Council, but he considered the school’s methods disrespectful to parents and older teachers.

Born in 1917, Romero occasionally had a “kids these days” attitude toward those who rushed to embrace the changes of Vatican II and the 1968 Medellin conference, a meeting that aimed to apply the teachings of Vatican II to the Latin American church. The fact that many seminarians no longer wore cassocks and let their hair grow longer annoyed him.

What drew his ire, though, was what Romero considered deliberate and politically inspired misinterpretations of Medellin by some members of the clergy. He took to the pages of Orientación to inveigh against “certain fashionable theologies.” His critics shot back that “the paper criticizes injustice in the abstract but criticizes methods of liberation in the concrete” and that its readership was “satisfied with the present situation” of landowners defrauding workers and the government providing the muscle to help them do it.

Romero never condoned violence and preached that workers must be treated fairly. He acknowledged that El Salvador had “a repressive military government” and an economy based on “cruel social differentiation, in which few have everything and the majority live in destitution.” But he also argued against the church working with the Salvadoran people for political change. Violence against civilians was a matter for the authorities to investigate, not for priests to loudly and harshly denounce.

Elevated to archbishop of San Salvador in late February 1977, Romero strove to maintain an apolitical approach to El Salvador’s worsening violence. To address the situation, the country’s bishops met on March 5, 1977 and wrote a letter denouncing the government’s human rights abuses to be read at all Masses a week later. The document stated “even at the risk of being misunderstood or persecuted, the church must lift its voice when injustice possesses society.”

Romero approved of the letter, but as Sunday drew near he began having doubts. The letter called out those living “an opulent life” while many others “live in habitual unemployment with a hunger that debases them to the direst levels of malnourishment.” Romero worried reading these criticisms would offend the wealthy parishioners at San José de la Montaña, where he was scheduled to say a Mass on March 13.

Then, on March 12, 1977, security forces murdered Romero’s friend, Jesuit Father Rutilio Grande. Grande did not share Romero’s caution and respect for authority. In a sermon two months before his death, Grande denounced the government: “If Jesus crosses the border, they will not allow him to enter. They would accuse him, the man-God . . . of being an agitator, of being a Jewish foreigner, who confuses the people with exotic and foreign ideas . . . . Brothers, they would undoubtedly crucify him again.” Learning of Grande’s murder, Romero drove to Grande’s parish in Aguilares, about 30 miles from San Salvador, to mourn his friend and say Mass.

The next morning back home in San Salvador, Romero said two Masses, one at the cathedral and one at San José de la Montaña. He read the bishops’ letter to both congregations and broadcast it on national radio. After that, there was no turning back.

For the remaining three years of his life, Romero pursued the truth wherever it led him, and it led him to embrace a church of and for the poor in a way he never had before.

His homilies detailed their struggles, each week giving a summary of the murders, disappearances, and attacks on workers and organizers and reporting on how eyewitness accounts differed from official accounts. Explaining the reason for this seemingly grim practice Romero explained, “My sermons are not political. Naturally, they touch on politics and they touch on the reality of the people, but their aim is to shed light and to tell you what it is God wants.”

In a 1978 homily Romero told his countrymen, “There will be no true reconciliation between our people and God as long as there is no just distribution, as the goods of our Salvadoran land do not bring benefits and happiness to all Salvadorans.” A stunning statement from a man who fewer than two years earlier fretted about the church being too political and susceptible to Marxism.

Conversion is often a dramatic plot point in a saint’s life—St. Paul on the road to Damascus getting knocked off his horse and blinded. St. Francis of Assisi denouncing his wealth and stripping naked. St. Ignatius of Loyola getting hit in the leg by a cannonball. Even in this illustrious company, Romero’s conversion is remarkable. A perfectly reasonable reaction in the wake of Grande’s murder would have been for Romero to continue his pastoral work while pursuing even more vigorously his instinct for caution and respect for authority. Instead, in the face of terror and fear, Romero changed.

Changing to better understand reality, changing to seek the truth, changing no matter how terrifying or dangerous the path may be, the struggle of change is the model of saintliness Óscar Romero offers us. When we see others engaged in this struggle, acknowledging them with “you’re a saint” is genuine praise.

This article is also available in Spanish.

This article also appears in the October 2018 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 83, No. 10, pages 23–24).

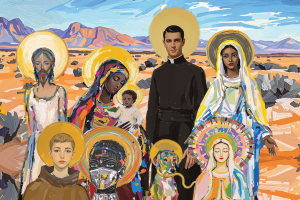

Image: via Wikimedia Commons

Add comment