When Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press around 1440 in Germany, everything changed. For the first time, words didn’t have to be meticulously hand-copied and multiple copies of books could be printed at one time. The first book to be mass printed? The Bible. Finally the sacred text, long the purview of monastics and the wealthy, became available to everyone—regardless of class.

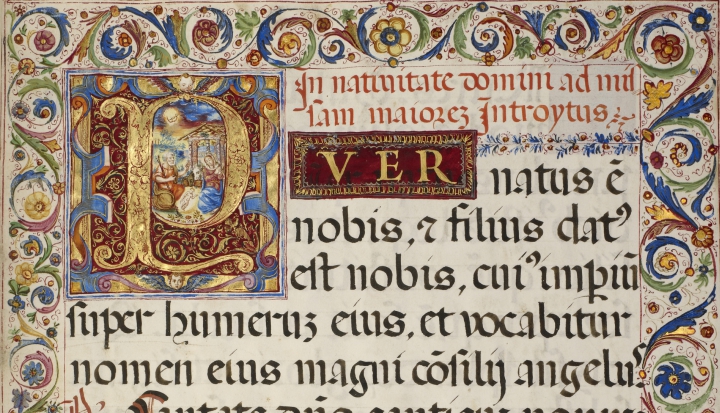

But the Bible had existed in print long before Gutenberg’s printing press. In the Middle Ages, it was largely monks who printed and bound books of scripture—by hand. The process was painstaking. The results were beautiful. They reproduced the words in delicate calligraphy, and images accompanied the stories. Each page was a unique work of art and a testament to the beauty of God’s word.

Referred to as “illuminated manuscripts,” these books were not widely available. At first they were used only for private worship in the monasteries where they had been created. Some secrets can’t be kept forever, though, and soon members of the ruling class and high-ranking church officials wanted their own illustrated texts. They began paying these monks to create original copies of the Bible specifically for them. Eventually demand grew past the ability of monks to meet it, and by the 12th century religious orders no longer had the monopoly on bookmaking. Secular artists and scribes saw value in the manuscript-making business and took up the craft. But each copy of the Bible took years to make, so the manuscripts remained few and far between.

Today perhaps the most famous remaining illuminated manuscript is the Book of Kells, located at Trinity College in Dublin. Every year more than 500,000 visitors view the book, far more than ever would have seen the manuscript when it was new. However, even given the Book of Kells’ popularity, you are still hard-pressed to find anyone who has seen an illuminated manuscript in person. For centuries, these books remained just as rare and precious as they had always been.

This has changed, however, thanks to recent advancements in technology. Scholars have begun teaming up with technological experts to scan illuminated manuscripts, publish them online, and bring this art form to the world. Today, people around the world can view medieval art and come to appreciate what these manuscripts reveal about human history. New audiences are coming to appreciate the monks’ careful and contemplative practice. These works are remarkable in how they translate faith into art and bring to life the word of God.

Making the medieval modern

No one knows how many illuminated Bibles were created or how many still remain, over 1,000 years later. But thanks to new technology, experts are starting to get a clearer picture. In 2013 the Vatican began a project called “Digita Vaticana” that plans to digitize more than 80,000 of the manuscripts currently held in the Vatican Library. But this isn’t as simple as it may seem. Because the documents are so old, an expert with a careful hand must scan the pages. So the Vatican reached out to Japanese information technology firm NTT Data, which supplied the Vatican with a special scanner that prevents the book bindings from being stretched and that is free from ultraviolet rays, which can damage the delicate pages. The project will take more than 15 years and will likely set the Vatican back more than 50 million euros. At present the Vatican library has digitized almost 7,000 manuscripts out of the total 80,000; visitors to the website can keep track of the progress via a live counter on the homepage.

In the United States, Harvard professor and art historian Jeffrey Hamburger has helped digitize nearly 4,000 illuminated works as part of an 2014 exhibit displayed in museums across Boston titled, “Pages from the Past: Illuminated Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts in Boston-area Collections.” “No longer is it always necessary to travel halfway around the world to consult a unique surviving copy,” Hamburger says. “Digitization also allows for easy comparison and sometimes new forms of online collaboration.” This includes communication between scholars. By comparing the works of different monks in different locations, for example, historians learn more about the illumination process and the styles of art people commissioned.

Even the casual art lover can learn something from having access to these new collections. “Digitization of medieval manuscripts has transformed our appreciation and understanding of these works,” says Hamburger. “For the public, for whom these fragile and precious objects are for the most part inaccessible, digitization opens up a world that would otherwise be closed to them.”

Faith in the margins

Medieval art is strange to the modern eye. The bodies are elongated and flat, the animals don’t resemble real animals, and most of the humans depicted are either doing odd things like dancing on their head or wearing solemn looks of despair.

However odd they seem, these paintings were vital to understanding the text. The vast majority of people in the Middle Ages were illiterate. Even the educated wealthy had a limited understanding of the gospel, since few spoke or read Latin, the language of liturgy and scripture. The images within the pages of these illuminated manuscripts, though accessible to only a few, opened up a way for the public to understand scripture.

Today’s viewers face some of the same barriers when first encountering these manuscripts. “Ancient manuscripts can seem unapproachable,” says Hamburger. “They are written not only in unfamiliar languages (Greek, Latin, Anglo-Saxon, the medieval vernaculars) but also in unfamiliar scripts.”

But Hamburger says this shouldn’t dissuade viewers from browsing the vast collection of manuscripts available online. He says that while many are beautiful objects in and of themselves, they can also tell us about human life of the time. “They cover just about every area of human activity,” Hamburger says, “not just theology, prayer, devotion, and liturgy, but also law, medicine, history, romance, epic, poetry, almanacs, astronomy, and astrology.”

For example, one image of Christ’s resurrection includes medieval knights, who are falling over in awe of Christ’s return. Viewers see not only a medieval artist’s take on the resurrection but also how the artist thinks Christ’s friends and contemporaries would have reacted to the risen Christ. “The images in these manuscripts do not just reproduce the information in the adjoining texts, they comment on them as well, providing a different perspective that enriches our view of the past,” Hamburger says.

In an interview with Christianity Today, John Van Engen, professor of history and head of the Medieval Institute at the University of Notre Dame, explains some of the misunderstandings about life in the Middle Ages, particularly around religion. “Our image of the Middle Ages has been colored,” says Van Engen. “[During the Reformation], Protestants tended to paint the Catholic Middle Ages in very black terms in order to justify the kind of radical changes they sought.” To the outside world, Catholicism during the Middle Ages looked bleak and violent, a stereotype that remains today.

Illuminated manuscripts show a more complicated picture, however. Not all images show torture or self-flagellation in the name of faith. There are many paintings that instead show everyday scenes, such as one that depicts a group of women working together to complete chores. The women help each other wash large sheets and carry baskets to and from an idyllic-looking village next to a placid river. In no way does this image connote the violence or dirtiness that is often associated with medieval society. Instead it gives readers a better understanding of what life was actually like in the time of illuminated manuscripts.

More than memes

The attraction of medieval images to modern viewers is about more than religious education or a picture of life in a bygone era. Many of the images are strange, funny, or just downright grotesque. Entertainment websites feature articles with such headlines as “35 Medieval Reactions That Will Never Stop Being Funny” (Buzzfeed) and “17 Medieval Paintings That Perfectly Summarize Life in Your 20’s” (Thought Catalog).

Of this phenomenon, Hamburger says that “medieval art is endlessly interesting—and entertaining, especially the satirical, grotesque, and often obscene imagery that, at least from a modern perspective, rather incongruously populates the margins of religious books.” While today grotesque has a broader connotation, the images Hamburger references refer to the word’s original meaning—figures that combine a human face or parts of the body with that of an animal. Other images are appealing just because they are unexpected: an image of hedgehogs collecting nuts, for example. The monks who created these books did not always limit themselves to pious art—it is likely they never intended many of the more unexpected images to comment on the text they accompany, instead including them solely for humor.

Other images, according to Hamburger, reinforce societal taboos. “From a modern perspective, such images can seem very strange,” says Hamburger. “That foreignness . . . is a source of boundless fascination and curiosity.” These taboos are often of a sexual nature and are sometimes reinforced by an image of the devil alongside some obscenity—perhaps not what we typically think of when we imagine religious art.

Other images that discomfit modern viewers—like those showing self-flagellation—are crucial to understanding how the Catholic faith has changed over time. While modern Christians frown on many practices of extreme piety that involve bodily harm, they were an important part of many medieval Christians’ spiritual lives. “People in the Middle Ages had a strong sense they were to love God not just with their minds but also with their bodies,” explains Van Engen in Christianity Today. “By disciplining the body and its passions, they believed they disciplined their souls, pleased God, and prepared themselves to receive grace.”

It is rare that any artwork from so long ago finds any legs in today’s world. And yet illuminated manuscripts have been preserved, both as a tool to understand history and faith and simply to be admired. These images “are precious, not on account of their monetary value, but on account of their being a vast storehouse of information and ingenuity that never ceases to astonish and amaze,” says Hamburger. He adds that with digitization these works of art can continue to “astonish and amaze.”

A version of this article also appears in the July 2017 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 82, No. 7, pages 32–37).

Image: Via Getty Open Content

Add comment