It seems clear by this point that some spiritual experiences can be observed in the brain. But is it possible to use what scientists are learning about the brain to actually improve our spiritual lives?

The idea of the brain as a muscle is not new: Some proponents of the 19th-century pseudoscience of phrenology, which claimed that the shape of the skull reflected its contents, argued that mental exercise could promote the growth of desirable skull bumps. Today, companies like Lumosity promote “brain-training” to improve concentration and memory. And scientists who study spirituality say that practicing certain kinds of prayer or meditation over time leads to observable changes in the brain.

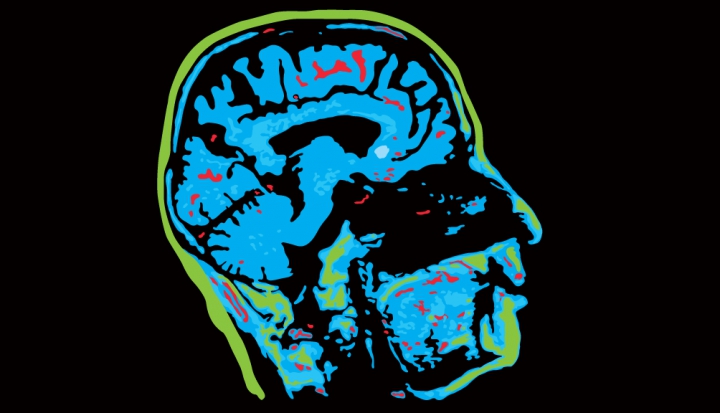

Andrew Newberg, a neuroscientist who has conducted brain scans on Franciscan nuns, wrote a book, How God Changes Your Brain (Ballantine), making the case that spiritual practices “enhance the neural functioning of the brain in ways that improve physical and emotional health.”

“There’s a fair amount of evidence that these practices literally change your brain over time,” Newberg says. Generally speaking, he explains, the brain works as a muscle, and “exercising” certain connections strengthens them. His own research suggests that meditation, for example, increases brain activity in the frontal lobe and changes its central structure, the thalamus.

Brick Johnstone, a professor of health psychology at the University of Missouri who has studied the issue, compares spirituality to learning to play a musical instrument. “We all are born with certain levels of traits or abilities, but you can hone those,” he says. “Some people are born with amazing musical talents, and others are born with none.” But no matter the starting point, almost everyone can inch themselves forward.

If you talk with people who practice centering prayer meditation, they may not use the language of neuroscience, but they echo the notion that their practice pervades the rest of their lives. “I feel like I’m experiencing the presence of God throughout the day as a result of this practice,” says Sue Fox McGovern, who practices centering prayer throughout the week. “I feel like it has really become a part of who I am.”

Phil Jackson, who has been practicing centering prayer since the late 1990s, says it’s not just about prayer time itself, but about the way it affects the other parts of his day, including other religious experiences. “The Mass, and the liturgy in general, has much more meaning, more of a felt presence of God,” he says. “The Eucharist itself is tremendously more meaningful to me. Centering prayer gives you a felt presence of God.”

This is a sidebar that accompanies “Of two minds: Are brains hardwired for faith?” which appeared in the June 2014 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 79, No. 6, pages 12-17).

Image: Angela Cox

Add comment