In this first installment of a two-part meditation, we are reminded of Abraham's "daddy issues." Even this exalted father of faith had a rocky start.

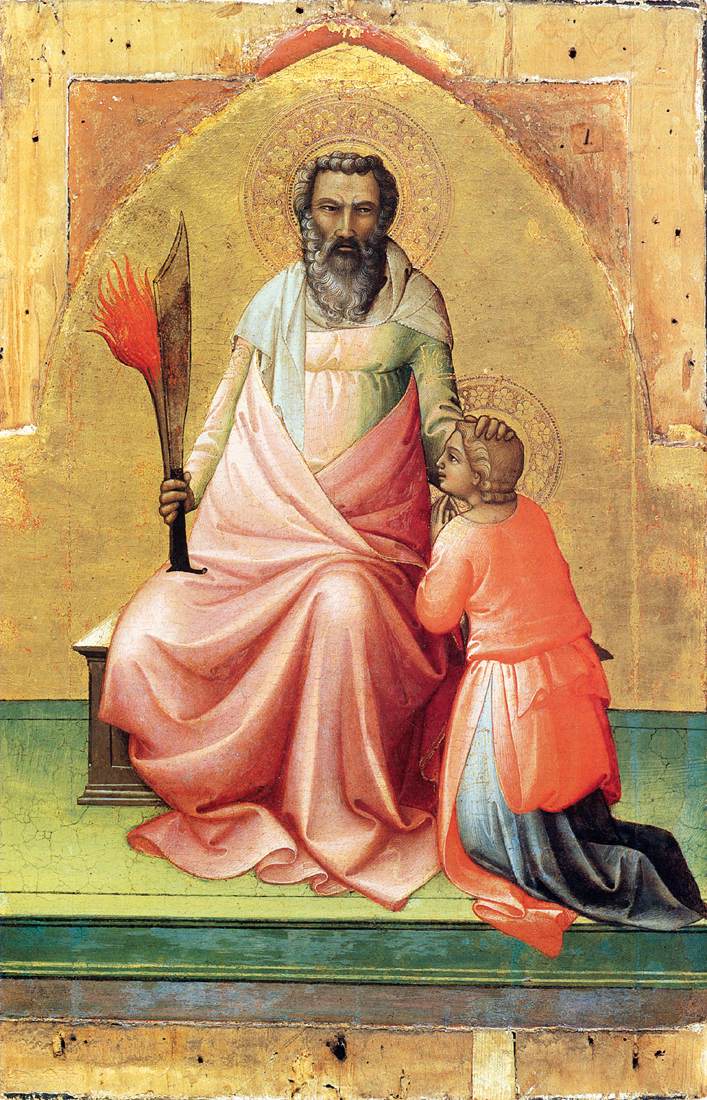

Lorenzo Monaco (circa 1370(1370)–circa 1425(1425)) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

It's been said there no good fathers in the Bible. Some will protest that Joseph of Nazareth did all right by his foster son. The extra-biblical tradition tends to fill in some pretty favorable details about that relationship.

But the Holy Family aside, there's little evidence that the majority of biblical fathers did well by their children.

It may be no coincidence that Jesus recommends we call no man our father. "Our Father who art in heaven" has all the paternal bases covered; the comparison to earthly dads on the biblical record is precipitously downhill from there.

Take Abraham, father of nations. Jewish scholars have gone so far as to call Abraham a "dangerous father," and the evidence is compelling. His two most famous sons are treated in a way most of us would be quick to report to the Department of Family Services.

Ishmael, his oldest, is abandoned in the desert along with his mom. Isaac, the favored son, is nearly sacrificed at knifepoint to appease his father's God.

How in the world did Father Abraham arrive at such a disastrous parenting style? If the book of Genesis is taken at face value, there was plenty of precedent.

Adam and Eve start out a fairly happy couple-though it must be said, pickings were slim for alternatives. Adam once declared his mate "bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh," making the honeymoon phase of the relationship seem sweetly promising. But after the passage of time, under a fateful tree, we see their relationship considerably diminished.

We know little of them after they leave the garden, except to see the fruits of their relationship borne out in their sons. The oldest, Cain, murders the younger Abel out of pure jealousy. Cain viewed Abel as God's favorite, the one who inhaled all the love in the room and left nothing for his brother.

This finger-pointing is familiar. When parents do not take responsibility for their actions, they pass this example on to their children. Cain blames Abel for his own inadequacies, and violence comes into the world as a result.

A spate of begetting ensues, with the next murder by Lamech just a few generations later dramatically underreported. Wickedness seems so irreversible that Genesis depicts God repenting the creation of human beings. If only God had taken the whole weekend off that first week, creation might have remained serene–without the potential blot of humanity and its freedom.

According to an Islamic story, when God first imagines free will, he offers it to the heavens, the mountains, and the earth in turn, but each refuses such a dubious gift. Finally, God extends this offer to humanity: the capacity to both remember and forget the divine will. And humanity fatefully declares, "Why not?"

By the time Noah comes on the scene, "Why not" is painfully obvious. God has shortened the life span of mortals to 120 years to limit the damage each can do. Even this measure fails to curb the prevalence of evil in creation, so God resolves to destroy most of the earth and its creatures. Noah and his family alone will be spared. The eight of them board the ark, and it seems to be clear sailing in the beginning for the new First Family.

Maybe 40 days and 40 nights of enforced togetherness brought them to rum. Family vacations that are far shorter, and with more leg room, can strain the tightest domestic bonds. Once their zoological incarceration ends, Noah makes a beeline to the vineyard and invents wine. The results are not pretty.

The new First Dad becomes the first drunk. The youngest son, Ham, finds his father toasted, not to mention exposed, and can't resist dissing the old man. Noah's other sons are quick to hide their father's humiliation, but it's too late. When Dad wakes up, he curses Ham's descendants–which is how the doomed children of Canaan get into the story.

More begetting leads to Babel, which leads to babble of another order. Multiple nations and languages create a multiplication of religions as well. When a fellow named Terah in Ur of the Chaldeans (later Babylon) has three sons, he has plenty of gods to choose from to entreat on his family's behalf.

But none of Terah's deities get the job done. His youngest son, Haran, dies early, leaving an orphan named Lot. Terah's middle son, Nahor, does all right, eventually becoming the grandfather of Laban and Rebekah.

But it's Terah's oldest, Abram, who is the most troubling. Abram can't seem to beget at all, despite more than a half century of marriage. Terah seems weary of the insufficient divinities of Ur, which have lost him one son and effectively truncated another. So Terah "takes" Abram–the verb is dismissive, like he's an object to be pocketed–along with Abram's "useless" spouse Sarai and the fatherless Lot, and determines to go to the land of Canaan for a fresh start. But Terah never gets there.

What went wrong with the plan? Perhaps it's as simple as this: An old man finds change an unsettling proposition. Halfway to Canaan, Terah puts it in park in a place he apparently names for his dead son, Haran. Terah left the land of the Chaldeans but cannot shake the tragedies of his past. He resolves to five circumscribed by the memory of his losses.

So Abram finds himself confined to his father's house, living with a childless wife, a fatherless nephew, and his brother's ghost. Abram's name, in fact, can be translated as "My father is supreme," pointing to Terah, not to Abram's own achievements. Are we surprised this fellow has issues?

When Abram encounters the Lord God, he's granted clemency at last. God promises him a future in the form of land and heirs. First Abram must do one thing, but it's a very crucial thing: "Go!"

Abram left Ur behind when his father "took" him. Now he must let God take him farther: beyond the old gods, beyond his father, beyond the constrictions of a fruitless past. Abram must become his own man so that a son once named for his father's glory can become "the father of nations" in his own right.

Abram tries in many clever ways to become Abraham. First he adopts Lot, but his dead brother's son will not serve as an appropriate heir. Lot is greedy (he takes the better slice of grazing land when Uncle Abram offers him a choice). Lot is foolish (he throws in his family's fate with the wicked people of Sodom). Lot is weak (he requires rescuing more than once). Most of all, Lot is a rotten father himself (he invites his rowdy neighbors to violate his virgin daughters in lieu of his guests).

Abram turns next to his servant Eliezer, offering his inheritance to this faithful member of his household in the event that he never sires the promised descendant. Let's face it, Abram s really old now. He was 75 when he finally moved out of his father's house in Haran, and he's a decade past that now. But God comes to him again and renews the dual promises of land and heirs. It's no wonder this time Abram asks for proof. God grants him a terrifying covenant of blood and fire.

Yet afterwards, Abram falls in when Sarai, now tired of God's promises, offers him her maid Hagar. This third attempt at becoming the father of nations is more successful. Hagar bears him Ishmael. But Sarai's jealousy will prompt her husband to abandon this fledgling family in the desert. The son of a death-oriented father has become a deadly dad in his own right.

This article appeared in the February 2010 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 75, No. 2, pages 44-46).

Add comment