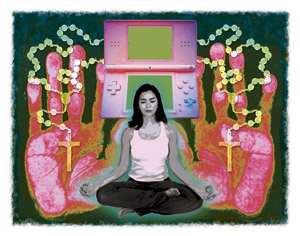

These aren't your grandma's devotions. Young adult Catholics are using non-traditional ways to get in touch with their spiritual side.

It's 11 p.m., and 31-year-old Tara Turner is wearing cotton pajamas, lying on her bed, deep in prayer. Her hands aren't folded; they're clasping a pink Game Boy.

As she digs to the center of the earth, attacking monsters en route, Turner communes with God.

"I pray as I play," she says. "When you've got your fingers and your eyes focused on this little critter on the screen, then your mind is more open to hearing God."

The medium is powerful for the Oklahoma native. "The only time I hear God speaking just as much," Turner says, "is when I pray the rosary."

Welcome to the prayer lives of young adult Catholics. Here, electronic monsters align with Hail Marys and digital pictures coalesce with the Stations of the Cross. Their prayer is startlingly expansive, a hybrid of the ancient and the high-tech.

It's a popular lamentation today that young Catholics don't pray. And research reinforces it. In 2004 the National Opinion Research Center found that 18- to 30-year-olds pray less than every older segment, while Catholics pray less than other denominations. The spiritual prognosis for young Catholics appears grim.

But there's more to the story, insists sociologist Dean Hoge, who interviewed hundreds of American Catholics ages 20 to 39 for his book Young Adult Catholics: Religion in the Culture of Choice (University of Notre Dame Press) and has taught thousands at Catholic University of America in Washington. Young Catholics pray in a wide variety of ways, Hoge says, some of which don't trigger affirmative survey responses. Don't dismiss the church's youngest members just because they don't enlist St. Anthony when they misplace their iPods.

"Young adult Catholics in America are unlike any in the past," Hoge says. "They're more educated, more affluent, better traveled, more culturally sensitive, more in touch with non-Catholics than ever in American history."

Each of these facts influences their prayer habits. For example, well-educated young Catholics yearn to infuse spirituality with intellectualism.

That yearning is evidenced in Cory Rath, 30, from Iowa City, Iowa, who read the biography of St. Ignatius and then bookmarked a website with daily Ignatian prayers, sacredspace.ie. "The intellectual component grounds my prayer life in experience and helps me to apply insight gained in prayer," Rath says.

Then there are young adults who "pray the news," incorporating the daily news headlines into online prayer. It is as spiritual as it is intellectual, uniting the news junkie and poet.

East meets West

In Catholic colleges across the country, theology and religious studies departments are offering more courses off Catholicism's beaten path. The movement has compelled Catholic students to view spirituality more broadly.

The University of Notre Dame, for example, has expanded its offerings to better meet the multi-faceted interests of its theology students. It's not uncommon for a student to study St. Augustine, Christian-Muslim dialogue, and social justice with equal interest, says John Cavadini, chair of the theology department at Notre Dame.

At Xavier University in Cincinnati, theology majors are now required to take a course on a non-Christian religious tradition. Xavier students explore meditation with Sister Rosie Miller, O.S.F. Her annual course in meditation routinely receives more applicants than its cap of 25 permits. "The students are very interested in learning to develop that skill," Miller says. "Meditating is a way of coming to a sense of groundedness in a very chaotic world."

Not only are students' textbooks more diverse, so are their travels. Generation Y Catholics, or roughly those under 30, have traveled more than any previous generation, pressing into more exotic corners of the globe. They're passing on Paris and Rome and opting for Beijing and Seoul, gaining influential exposure to Eastern religious thought.

"Buddhism connects with a lot of young adults," says Mary Jansen, director of young adult and campus ministry in the Archdiocese of San Francisco. After all, many early leaders of the Catholic Church were ascetics and cloistered religious, as Buddhist monks and nuns are today, Jansen points out. Plus, both religions endorse respect of the earth and God's creatures.

The presence of other religious traditions enriches an experience for Sarah Nolan, 27, a community organizer for the Archdiocesan Office of Public Policy in San Francisco. When she lobbied for children's health insurance with a group of 400, she found the interfaith makeup invigorating.

"We were Jews, we were Baptists, we were Catholics," she says. "It reminded me that our tradition is linked and meshed with all these other traditions. We're all part of this long line of prayer and action that doesn't just stay within Catholicism but branches out."

Nolan says her peers share her perspective. "Young Catholics know that our faith [doesn't exist] in a vacuum. We're rooted in traditions that are much older than we are, and we've created traditions that other religions are rooted in as well."

The willingness to identify commonalities among various traditions is a signature of modern Catholic youth. "The religion of young adults, more than a generation or two back, has an unboundedness," Hoge says.

Being "unbound" doesn't quite square with Pope Benedict XVI's emphasis on the uniqueness of Christianity. Then again, young Catholics tend to be more influenced by the spirit of Pope John Paul II's long papacy than the letter of Benedict's nascent one. Although John Paul II never said all religions are equal, he demonstrated an unprecedented respect for other traditions. He prayed in a mosque, kissed the Qur'an, and called Jewish people "our elder brothers."

These gestures left a lasting impression on globe-trotting gen Y Catholics. They're comfortable mixing prayer forms, considering the spiritual benefits of the Stations of the Cross and yoga alike.

Every Monday night Lori Casey teaches yoga at Holy Spirit Catholic Church in Rochester, Minnesota. During the month of May, Casey and 20 students recited Hail Marys while holding a palm-to-palm pose.

Some positions are conducive to contemplation, Casey says. "When I'm in the ‘exalting' pose-a lunge when you raise your arms overhead, clasp your hands and look upward-what comes to my mind is, ‘Lord, what do you need of me? I am your servant,'" Casey says.

Marina Kemp, a 35-year-old nurse, says she found a spiritual home when she joined the yoga class. Baptized Catholic, Kemp had drifted while attending a Lutheran college and after graduating. "When I went to Lori's class," Kemp says, "I really felt a fit. ‘OK, this is it.' It brings it full circle-mentally, spiritually, and physically."

Yoga also relieves stress, Kemp notes.

That's a benefit of massage as well, says Margaret Mendolera, 41, a massage therapist from Auburn Township, Ohio. "Having a massage releases tension and grounds you, which enables you to go inward."

Medonlera is an active Catholic, and she encourages her clients to pray during their sessions. "I try to coach them into taking deep breaths and centering themselves, to forget about why they're late or where they're going and just be in the moment."

Mixing old and new

Mendolera is one of many young adults who links prayer to stress relief. Others pray during pedicures. But even if tranquility is a pleasant by-product of prayer, it isn't considered the primary purpose, according to traditional approaches to prayer; we pray to draw closer to God and more closely confirm to God's will. That's a distinction that young Catholics today appear less prone to make.

But in their favor, this much can be said: Young Catholics are remarkably agile when it comes to prayer forms.

Josephine Canales, director of young adult and campus ministry for the Diocese of Austin, Texas, taps into that agility with her prayer group, "Wine, Women, and the Word." There, she introduces young women to lectio divina, the Benedictine practice that includes prayerfully repeating and meditating with sacred scripture several times a day, as well as to mandalas, an ancient Eastern art form in which one contemplatively draws around a sacred text. The women are open-minded and grateful for the diversity of devotions, Canales says.

"Art brings me deeper into myself and makes me work out my thoughts," she tells the women. To deal with her father's illness, for example, Canales wrote a short line from a psalm-"God, you will heal me"-on her mandala and then drew images around the words in purple, her father's favorite color. "Every time I say the verse, it means something different," Canales explains. "You will heal our relationship. You will heal my father. You will heal me when I lose him."

Karissa Ryant, 24, a Mary Kay consultant from Cedar Rapids, Iowa, finds spiritual power in modern ways-like during her commute. She drives into the sunset every evening, which fills her with an awareness of God and a sense of gratitude. From behind the wheel, she utters the simple prayer, "Thank you."

Painting is another act of prayer for Ryant. "It's like the brushstrokes are coming from God. I feel so connected to him."

The sense that she is dwelling in God's presence is profound, Ryant says. At the same time, it's simple. Her mind is emptied of the day's events and emotions. She isn't worrying or analyzing. She isn't thinking at all. She's just being. Painting allows her to exercise the command in Psalm 46:11, to "be still and know that I am God."

Ryant also practices a couple of traditional devotions. She prays an Act of Contrition daily and finds nostalgic comfort in praying "Now I lay me down to sleep" every night.

At the same time, she sees spiritual potential in cyberspace, the source of inspirational e-mail forwards that regularly give her pause from her work.

She's in good company when it comes to computer-assisted contemplation. There are many prayer blogs and countless social networking sites laced with scripture.

Scott Thomas, a 24-year-old seminarian from Jackson, Mississippi posts spiritual reflections on his MySpace page. "It helps ingrain it in my mind, and it's easy to revisit. If I'm going to give a talk, I'll go back to previous posts online."

And yet, like many young adults, Thomas is well rounded in his prayer habits. He also enjoys the Liturgy of the Hours, which consists of seven rounds of prayer-hymns, psalms, and scripture-that loosely conform to the hours of the day. "It makes me feel connected with the communion of saints in heaven because they're praying for us right now, praying for us to make it up there, to join them in paradise."

Many young adults find the chords of contemporary praise and worship music heavenly. The diocese of Houma-Thibodaux in Louisiana hosts a monthly "Adore" night that draws 1,000 teens and young adults. There, modern religious music enhances the traditional practice of eucharistic adoration.

"They're very open to a combination of new and old prayer forms," says Paul George, the diocesan director of young adult ministry. "I've found that when you combine the ancient and the modern, it's a good mix."

All roads lead to God

If young Catholics are uttering "Our God is an awesome God" instead of "Glory be to the Father," what's the difference, Hoge asks. "Faith is not optional, but specific devotions are. If they don't have spiritual power, something else will."

Retreats and service programs, for example, are surging in popularity, while the rosary is fading. "I don't think we should grieve over something like that," Hoge says, because the rosary is not the sole path to holiness.

Even St. Thérèse of Lisieux wrote in her autobiography, The Story of a Soul, that the rosary was torture for her, says Amy Welborn, the author of The Words We Pray (Loyola).

That's not to say traditional devotions should be dismissed, she adds. But their function in contemporary culture should be considered carefully.

"Sometimes I hear, ‘Our young people need to learn to pray our devotions because it's an important part of Catholic identity.' It's like, ‘They'll know we are Catholic by our rosaries.' To me, that's not right. We pray these prayers because millions of Catholics before us have connected to God in meaningful and profound ways through these traditional prayers."

Rather than grieving dying devotions, we should celebrate the breadth of prayer young adults are practicing, Hoge says. Take the young Catholics in San Francisco who pray the Stations of the Cross with a September 11 theme, incorporating digital pictures.

"Young adults are creative even with traditional prayers," Jansen says. "And that's good news. It challenges us to constantly be thinking and evolving. We're an organic church."

Add comment