When it comes to figuring out what the Jesus of Christian faith has to do with the anthropological Jesus studied by historians, Catholics are lucky: They have lots of options. "For a Catholic," John P. Meier has written, "the full reality of Jesus Christ is mediated through many channels. . . . My faith in Christ does not rise or fall with my attempt to state what I can or cannot know about Jesus of Nazareth by means of modern historical research."

Yet, the quest for the historical Jesus-or "Jesus research," the term Meier prefers- does an irreplaceable job of making the Jesus of faith more concrete as an historical person who actually lived in first-century Palestine. Such is the task Meier has assigned himself in the first two volumes-with a third forthcoming-of his magnum opus, A Marginal Jew (Doubleday), which has become a standard work in the study of the historical Jesus.

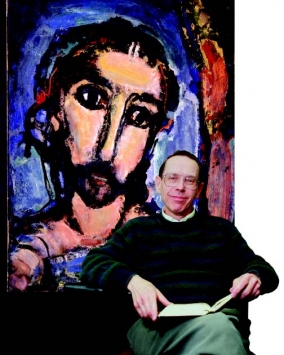

One of the foremost scripture scholars of his generation, Meier is professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame.

In a Marginal Jew you ask yourself, "Given all that's been done in historical Jesus research, why try this again?" What's your answer?

There are certain great questions that keep coming back, no matter how much we try to wipe our hands of them, and the question of the historical Jesus is one of those. If not in every generation then at least once or twice in every century, scholars will come back to it. On the popular level, as you can see from the endless books and TV programs on the subject, the appetite for information on the historical Jesus seems insatiable, which is a good reminder to academics who may put up their noses at it that this is a question of perennial interest for the ordinary person.

Which quest for the historical Jesus are we on now?

What we have now has been referred to as the third search or quest for the historical Jesus. The first one took place in 19th-century Protestant Germany and culminated in physician-theologian Albert Schweitzer's rather negative evaluation of it at the beginning of the 20th century, arguing that too much of it was projecting the researchers' values onto Jesus.

The second quest revolved around the disciples of the German scripture scholar Rudolf Bultmann in the 1950s and early '60s, and it was taken up here in the U.S. by people like James M. Robinson and others, who were influenced by an existentialist approach to Jesus. It had its day, but it really didn't have all that great of an impact-certainly not as much as the first, which took up a good part of the 19th century.

One thing that marks the third quest is the seriousness with which the Jewishness of Jesus is taken. Jesus must be understood as a Jew within the context of first-century Palestinian Judaism-nothing else. One must carefully distinguish a purely empirical, scientific quest for the historical Jesus from what we know through faith-the New Testament's theology of Jesus-its Christology.

It's only recently that Catholics have come to the realization that the study of the historical Jesus is not simply a subdivision of Christology, which is how Catholics first started gingerly to deal with it. If it's really a historical study, then it has its own autonomy.

One of the other things that makes the third quest different is that for the first time you have a fully international and ecumenical religious quest for the historical Jesus, which makes for richness.

What are the main features of the historical Jesus?

First, Jesus' roots are Jewish; he comes out of the Jewish prophetic and wisdom traditions. He presents himself-and just about everybody agrees on this-as a Jewish prophet with a message of the kingdom of God, which is coming in its fullness, but in some sense is already present in his ministry, preaching, and healings.

He is an eschatological prophet, that is, he is speaking of the end-not the end of the world but the end of Israel's history as it's been known up to that time. A definitive change is coming in Israel's history. The kingdom of God is not just an abstraction; God is coming in power to rule his people of Israel, directly and definitively.

Jesus sees himself very much in the guise of an Elijah-like figure, not only a prophet but also a miracle worker and healer. But he is more than that; he is also a teacher of the Mosaic law and a wisdom teacher who speaks in aphorisms and proverbs. Significantly, Elijah was expected to return and gather the 12 tribes of Israel back together. Jesus is doing a similar thing, traveling back and forth from Galilee and Judea, trying to embrace all of Israel with his message. Jesus' act of sending the 12 disciples out on a mission to Israel is a symbolic prophecy-in-action of regathering the 12 tribes of Israel.

In the final week of Jesus' life, after having been leery about the title messiah-especially a messiah who is the son of David-he plays the "David card" by chasing the money changers from the temple, purposely fulfilling the prophecies of Isaiah and Jeremiah. This symbolic-prophetic act may be intended to foreshadow the coming destruction of the temple. At the same time, however, the cleansing of the temple was perhaps also a kind of symbolic retaking of it. It reminded people that as long as there was a son of David, a Davidic king, the temple belonged to him and was his royal chapel-and the priests served at his pleasure.

Why do you distinguish between the real Jesus, the historical Jesus, and the theological Jesus?

Jesus of Nazareth did live in the first century A.D., but the vast majority of his life is totally lost to us and, short of some incredible discovery that seems unimaginable, will always be lost to us; we'll never know most of those 35 years. The historical Jesus that we're talking about is a theoretical reconstruction of maybe the last two or three years of this person's life.

Now that hardly coincides with the real Jesus in the totality of the 35 years he lived. All too often people equate the historical Jesus with the real: If we could only get to the historical Jesus, we could get to the real Jesus. But the historical Jesus is the Jesus of modern historians. It's very important to realize that the historical Jesus is a modern construct.

So right out of the gate, the historical Jesus is not the same thing as the real Jesus. If one then goes from the purely historical into the realm of faith and theology, then real takes on further nuances and meanings.

For the believer, the real Jesus encountered today, while certainly in continuity with that Jesus who lived on earth 2,000 years ago, is the crucified and risen Jesus encountered through the mediation of the community of belief in scripture, prayer, church teaching, faith, and sacraments. A believer, coming to the gospels in private prayer or in the liturgy of the church, doesn't have to have all this academic finesse.

For instance, the gospel I heard this morning at Mass was from Mark 6:53-56: Jesus is passing through the Galilean countryside, towns, and villages, and when people hear he's coming, they bring the sick to him on mats-whatever they can find-and they seek him desperately. It's such a moving scene: They want to touch even the tassel of his cloak, and all who touched it are healed. You don't have to be a scholar to understand the basic message there.

What is the significance of Jesus research for ordinary Catholics?

I can remember a bishop telling me that one of the lay administrators in his diocese was talking to him privately and saying to him, "You know, I'm quite willing to accept on faith and on authority what the church teaches about Jesus, but sometimes I wonder: Is the whole thing just a marvelous myth-are the gospels just marvelous stories? Are we talking about anything that really happened?"

The bishop gave him Volume One of A Marginal Jew. This person, with marvelous stamina, read the whole thing and came back and told the bishop how much it had helped him to realize that, indeed, we are talking about somebody who actually lived, that the doctrines of faith-while not being proved by historical research-are not just floating in midair without any reference to somebody named Jesus who actually lived in first-century Palestine.

I'm amazed at the number of e-mails and letters I get from people-not academics but "ordinary" Christians, Catholics and Protestants-who plow through the two volumes of A Marginal Jew and ask me questions about them. The main part of the text helps people to at least realize that the Christian faith is not something totally divorced from the reality of this first-century person named Jesus.

So how does faith fit in?

I think the ordinary person's faith can be enriched and nourished by the historical Jesus. At the same time, you have to remember that no historical Jesus existed until the 18th century. That's a good way to remind us of what "historical Jesus" means here.

For about 1,700 years you had Christians, some of them highly educated-like Saint Thomas Aquinas-and some unlettered, who each in his or her own way believed in Jesus and, among intellectuals, developed whole systems of thought without even thinking about what we mean by the historical Jesus. People whose faith no doubt is much better than mine got along very well without it, thank you, as no doubt Catholic peasants in Vietnam and San Salvador and Southern India do today. Is there something wrong with their Catholic faith or their Christian faith or their belief in God and Jesus? Obviously not. To be sure, the construct we call the historical Jesus is a legitimate intellectual concern for educated Christians in the modern Western world, marked as it is by historical consciousness. But the historical Jesus is hardly the basis of or the necessary precondition for genuine faith in Jesus Christ at all times and in all places.

Why do you refer to Jesus as a "marginal Jew"?

From the viewpoint of the Jewish and pagan literature in the century following Jesus, Jesus was at most a blip on the radar screen. The term marginal Jew is a way to shock Christians into the realization that Jesus was not a Christian but a Jew, and, far from appearing so important in his own time and place, to many educated people of the time he would have seemed very marginal.

Unfortunately, a number of people took it to mean that somehow I was questioning the Jewishness of Jesus or saying that he was only marginally a Jew, which is not the point at all. Jesus was a marginal figure in his time in world history. He wound up getting crucified, and you can't be more marginalized than being executed in public as a criminal.

Jesus was marginal, but was he poor?

From our point of view, Jesus would have belonged to the class of poor people, which is to say he was typical of about 90 percent of the people. Typical of ancient societies, you had a very small, rich, and powerful elite at the top of the pyramid, and the pyramid sloped down very quickly.

Intriguingly, though, Jesus never calls himself poor, and the gospel never calls him poor. Notice that "the poor" was the group that he relates to or speaks to: "Blessed are you poor." For instance, when the woman at Bethany anoints him by pouring the jar of oil on his head, people object to this terrible waste of a year's salary in one fell swoop. Her action was extravagant, but it reminds you that though he might have been poor himself, he had found rather wealthy supporters. He and his disciples were able to presume hospitality in various places.

But the intriguing thing is what he says by way of answering the people who object to this great waste of money that could have been given to the poor. It was given to Jesus, not to the poor. He describes himself as someone who is not included in the category of the poor.

So, judging from a purely economic and social point of view, with the great divide between rich and poor in ancient Palestine, Jesus belonged with the poor and not the rich. But he didn't especially see himself that way.

Unfortunately we have very little if any indication how Jesus' movement sustained itself economically. There was Jesus, his inner group of the 12, and apparently other disciples traveling with him, including a group of women. How is this itinerant movement sustained over a number of years? Obviously, a presumption of hospitality is quite important. There must have been fairly wealthy patrons because when Jesus arrived in town it was not just he who had to be fed and housed but also a group of disciples and a whole entourage. No wonder poor Martha was upset!

What does historical biblical research, in general, have to do with preaching?

One of my regrets right now is that, being outside my diocese, I have chances only now and then to preach.

When I taught at the archdiocesan seminary in New York, not only would I preach regularly at the seminary Masses, but I had a parish that I went to regularly every Sunday for 12 years, and I would preach twice every Sunday. The parish was mixed-blue collar, white collar, half Italian, half Irish, some second-, some first-generation Americans. Others were recent immigrants, from both Ireland and Italy.

Preaching there was a good way after an academic week to bring me down to earth and struggle with how one gets scripture across to people. Not only did I have to explain what the text was about, but I also had to face the question-and this is more difficult-Why should the people care? What does it mean to them?

I would try to explain what the text meant in its original situation, which often involved, among other things, trying to disabuse my audience of various ideas they might have had about what the text meant. And then, second, I had to ask: What does the text say to us? In other words, what did the text say to its original audience, and what does the text say to us today?

Every good homily tries to do both, and to do either of those tasks without the other is something of a deficit. If a homily is just historical exegesis, it becomes an academic exercise in many ways and people say, "So what?" On the other hand, we have endless pious musings about what this text says to me or what it says to us with no grounding in the actual historical significance of the text. It becomes purely whatever I want it to mean.

The parish priest is the best person to do the task of preaching. I could never know the parishioners the way the parish priests living with them day in and day out could. I'm a firm believer that only the full-time parish priest can really preach to his people with full-time parish priest can really preach to his people with full effectiveness, because only he knows what's gone on in the parish for the past week. He's immersed both in their lives but also hopefully in the text and in his own reading.

Add comment