This past April, controversial conservative personality Candace Owens announced on social media that she had “recently made the decision to come home.” The announcement was paired with photos from an Easter Vigil Mass, with Owens standing next to a priest in a church in London. In closing, Owens repeated a phrase that she had been using increasingly frequently: “Christ is King.”

This was not Owens’ first high-profile conversion. Until 2016, Owens ran a marketing firm that criticized conservative politics, including then-presidential candidate Donald Trump; however, she stated in multiple interviews that she became conservative overnight, switching gears and championing the Republican party while releasing provocative commentary on her YouTube channel such as “I Don’t Care About Charlottesville, the KKK, or White Supremacy.”

Her conversion to Catholicism makes those Catholics who do not support her history of antisemitism uneasy; however, other Catholics are either willing to overlook her conspiratorial views or are themselves in agreement. In May 2024, Owens publicly shared her conversion story at the Catholics for Catholics-sponsored “Welcome Home Candace Owens” event. During her hour-long speech before the gathering of Catholics dedicated to reelecting Donald Trump, Owens drew comparisons between her denunciation of Black Lives Matter and her waking up to the truth of Catholicism.

Since her conversion to Catholicism, Owens has embraced antisemitic conspiracy theories even more fully. On her YouTube channel, which has more than 2.2 million subscribers, Owens recently posited that the Star of David originated from a child-sacrificing pagan deity and claimed that Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the first president of Turkey and the driving force behind the Armenian Genocide, was actually secretly Jewish. Several other videos on her channel seem hyperfocused on Jews and their place in society.

Owens is not the first famous person to convert to Catholicism and use their newfound faith to espouse heterodox beliefs. And she is representative of a larger, and troubling pattern: Emulating celebrities and holding them in high regard has been a significant part of the culture at large for decades. If a famous person endorses a product or promotes a point of view, many listeners take the celebrity’s word over that of non-famous experts.

Within Catholic culture, a similar phenomenon exists in which personalities with large platforms are viewed as more important or even more knowledgeable than experts on church teachings and tradition. While this may be simply human nature, idolizing fallible individuals and indulging in cults of personality can present significant challenges for the church.

The nature of celebrity

Thanks to digital and social media, any person, regardless of actual training, education, credentials, or even wisdom, can build a platform, find followers, and establish a fanbase. And among those influencers’ followers, many are seeking spiritual formation and even community, making it easy for these platforms to be abused.

Katelyn Beaty, author of Celebrities for Jesus (Brazos Press), believes strongly that the modern-day focus on personas, platforms, and profits is hurting the church. While her expertise lies in the evangelical movement, there is a significant overlap between Catholic and evangelical influencer culture. “We see in Hollywood and mainstream media that power and prestige shield against consequence, leading celebrities to misuse their power over people in different ways,” Beaty says.

According to Beaty, there are people entering ministry and leadership whose personalities lead them to seek positions of religious power in order to gain attention or prestige. But this leads to a disconnect between the public persona and the actual person, she says. And this is bad not just for a religious community at large but for the leader themselves. Humans require embodied relationships. “We need people who love us deeply, know us deeply, and can call us out,” Beaty says. “Some Christian leaders are drawn to celebrity because it feeds their desire to feel loved and accepted, but it’s a thin replacement for what we’re created for.”

Beaty also cautions communities that look up to such celebrity leaders. When such figures are found to have abused minors, misused church funds, or committed other transgressions, the effects can be catastrophic. “When you’ve gone to a church that has a celebrity pastor and you’ve looked up to this person as some kind of mentor, that can have a devastating effect,” she says.

A church at a communications crossroads

The internet and the growth of digital media mean that attention-seeking religious figures have an almost unlimited platform. In response to what he and a group of other writers perceived as attacks on the church from some of these online personalities, journalist Mike Lewis established Where Peter Is, a website dedicated to defending the teachings of Pope Francis. The name derives from a quote attributed to St. Ambrose of Milan: “Where Peter is, there is the Church.”

According to Lewis, the website seemed necessary because of what he describes as a small yet noisy group of critics who have a significant influence on media representation of the church and of the pontiff. Since establishing the site, Lewis has become increasingly frustrated by what he sees as a warping of church teaching as a result of aligning with celebrities. He also feels that the church has yet to sufficiently engage the media utilized by these polarizing figures, allowing them to gain a larger foothold than they might have otherwise.

However, Lewis says that there have always been cults of personality within the church. For example, the Feeneyites had extreme, heterodox, and antisemitic views on salvation and were around for centuries. Lewis also mentions Father Charles Coughlin, a prominent Canadian American Catholic priest during the 1930s and ’40s who was ahead of his time in terms of the widespread influence he gained through his radio programs. “Coughlin distorted people’s vision of the church, making it more apocalyptic, more paranoid, more reactionary,” Lewis says. “In such situations, the faith becomes more of a fantasy than about doing the hard work of living a Christian life and living out the gospel.”

However, there is a large difference between these historical figures and their influence and today’s Catholic cults of personality, thanks in part to the internet. “The internet has allowed these tiny fringe groups to expand and have a lot of influence over the culture, and for some reason in the United States this has taken on a life of its own,” Lewis says.

Uncomfortable celebrities

Most Catholics may have forgotten the Feeneyites and Charles Coughlin, but they probably remember some of the Catholic celebrities that gained prominence after the Second Vatican Counsel. For example, Kevin Ahern, the director of the Dorothy Day Center at Manhattan College and cochair of the Dorothy Day Guild, describes the followings of Dorothy Day and Jean Vanier, the Catholic theologian who founded L’Arche. Ahern says that when Day was alive and carrying out her work, the church was experiencing a period of uncertainty after the Second Vatican Council. “There was an experience of new ecclesial movements after Vatican II with an emphasis on the lives of their founders,” Ahern says. Ahern says individuals such as Jean Vanier, the Catholic theologian and philosopher who founded L’Arche and was later revealed to have abused several women, were viewed as “almost living saints.”

The Catholic Worker movement, which Day founded, rejects celebrity culture, and Day herself exemplified this rejection. She often appears dour and serious in photographs, clearly uncomfortable with the attention she received. “Dorothy resisted being put on a pedestal,” Ahern says. “She wrote in her diaries how she felt like she wasn’t deserving of the honor.”

There are always issues with glorifying the founders of these new movements. When someone such as Vanier is discovered to be far from holy or perfect, there is a risk of crushing disappointment and even a loss of faith. “We have a celebrity culture that makes people caricatures of themselves, which has caused a lot of disappointments, but the theology of sainthood is one that recognizes the humanity of the person,” Ahern says.

According to Ahern, it’s important to delineate between exemplar and celebrity. For Ahern, Day’s life is in direct contrast to the concept of celebrity, because her work always pointed towards others. But he does aspire to elevate her as an exemplar to follow for personal development. “Dorothy lived in community with people, cooked with them, shared living quarters with them,” Ahern says. “Perhaps the way we avoid celebrity culture is community, inviting key exemplars into our community rather than making them the center of it.”

The dehumanizing nature of celebrity

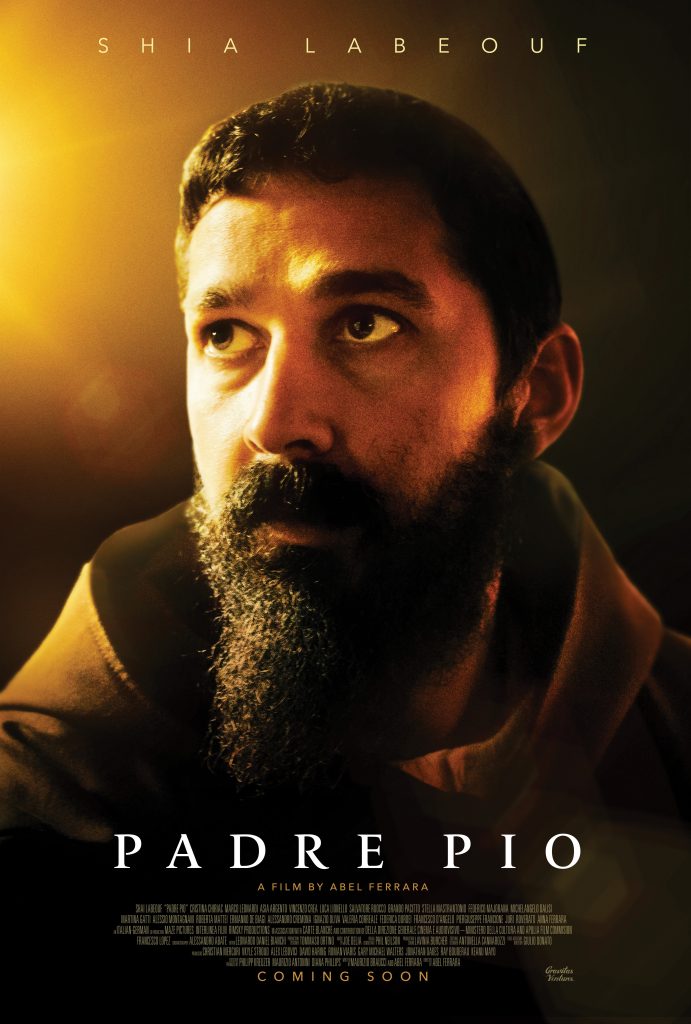

In addition to historical Catholic celebrities, current Catholics are faced with an increased number of celebrity converts. Recently, actor Shia LaBeouf went through the Order of Christian Initiation of Adults (OCIA). He spoke with Bishop Robert Barron at length about his conversion, noting the influence portraying Padre Pio on film had on his faith as well as the guidance he received from Mel Gibson, another celebrity Catholic. Catholics had mixed reactions to the public nature of his conversion, in great part due to ongoing controversy surrounding LaBeouf, who has been involved in legal matters related to allegations of abuse from a former girlfriend.

Catholic essayist Simcha Fisher used LaBeouf’s conversion and people’s ensuing reactions as a jumping off point in an essay for the Catholic Weekly in which she discusses the incompatibility of faith and fame. In this piece, Fisher poses the question, “How could it possibly be a bad thing for a celebrity to become Catholic very publicly, and open the possibility for lots of their fans to follow?”

Echoing Beaty’s thoughts on the use of celebrity as a tool, Fisher says that while fame can be useful, but it is not a virtue. “It can be very bad for people,” she says. “The more famous you are, the less people question what you say. We have to constantly remind ourselves to judge people on their merits—how would I feel if this were any other person doing it?”

Regardless of whether a person is famous, Fisher says they have a responsibility to love those whom God has put in their lives. “God has put each of us in a certain community and the people that we have most responsibility to are those with whom we have the most contact,” she says. “When you’re famous, you feel like you’re in contact with so many people but have less responsibility to them all.”

Fisher says that all of us have two responsibilities: love and care. And this also applies to how non-famous people treat those who are famous. “Just because someone is famous doesn’t mean they are better than us, but it also doesn’t mean they aren’t people, too,” she says.

While someone’s first impulse might be to make a joke about a celebrity or disparage them when hearing a bit of celebrity gossip, Fisher says to remember they have an immortal soul, too. “Maybe make it a habit to say a quick prayer for them instead,” she says. “We are all in need of mercy from one another and all in need of mercy from God.”

Reconciling past sins and looking forward

While the Catholic Church canonizes many people who lived virtuous lives, there appears to be a common misunderstanding among Catholics as to what that recognition means.

Lewis has noticed how many Catholics misinterpret canonization as a mark of infallibility, which is not the case. “There needs to be an understanding about what the church values in saints,” he says. “Not every aspect of every saint’s life is something that we should be emulating. They came from all different walks of life.”

Author, speaker, and theologian Dawn Eden Goldstein encourages Catholics to step outside of the team mentality she views in Catholic circles, particularly in American Catholic ones. “This is what Pope Francis talks about when he talks about reducing faith to ideologies,” she says. “It’s very much a problem on both ends of the spectrum.”

Goldstein encourages Catholics to regularly examine their consciences and ask themselves what motivates their response to Catholic celebrities. “Am I responding to this because it’s the moral position or because my ego is wrapped up in this personality that I’m defending?” she asks. “Am I willing to allow for the possibility of legitimate criticisms or have I so identified myself existentially with this person that any criticism of this person is seen as an attack on my own very identity?”

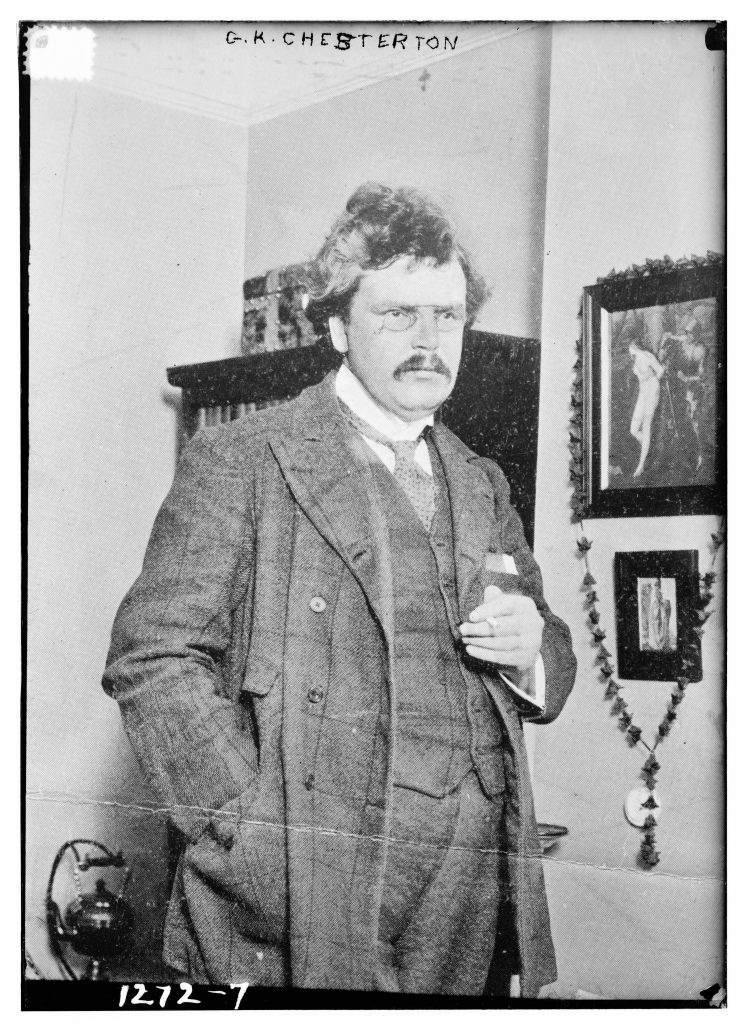

In her own work, Goldstein has tackled the issue of one such famous Catholic: G. K. Chesterton. As an admirer of his work, Goldstein felt an obligation to reckon with Chesterton’s antisemitism, even addressing the Society of G. K. Chesterton and encouraging them to do the same. Without such an acknowledgment, Goldstein fears that Chesterton will be relegated to history. “I don’t want Chesterton’s reputation to be irreparably harmed,” she says. “I want the community to say we repent of this on his behalf, and here is what is valuable in his writings.”

In her talk for the Society of G. K. Chesterton, Goldstein used Chesterton’s own writings to counter Chesterton himself. “We have to acknowledge that he, like all of us at some point, was a bloody hypocrite,” she says. “Just like we would want people to be honest about our own legacy.”

According to Goldstein, this is what intelligent and reasonable people do. “Good people are not afraid of legitimate criticism because they recognize that nobody except for Jesus and Mary is without sin,” she says. “We do our heroes no favors if we try to gloss over their sins.”

Similarly, author Gloria Purvis sees great challenges ahead in the ideological divide pervasive in many Catholic circles, particularly when it comes to matters of racial justice. Purvis herself was fired by EWTN, potentially due to her own boldness in discussing racial matters in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, although she has no regrets about speaking out.

Purvis is increasingly frustrated by the platforms provided to controversial figures such as Jordan Peterson, who she says utilizes language antithetical to Catholics, while the same grace is not offered to non-Catholic racial justice advocates such as Ibram X. Kendi and Robin DiAngelo. “There’s all the nuance for those who say racist things, but none for those who challenge racism,” she says.

Purvis continues to speak out about the problem of racial sin in the church. She would like those promoting polarizing figures to step up and address the racial evil in those to whom they offer a platform. “We see within the same Catholics this inflexibility in terms of their own examination of conscience within the sin of racism,” she says. “As they embrace people like Jordan Peterson who says some very problematic things about race, such as his reaction to the appointing of the first Black female Supreme Court justice.” (Peterson referred to Ketanji Brown Jackson’s appointment as “race-based hiring” on social media.)

According to Purvis, those offering platforms to celebrities have a responsibility to also speak up when they disagree with them and offer reasons why their positions are not in line with Catholic teaching. “We try to make excuses for people’s sinfulness instead of just looking at it head on and making reparations to the human family and to God for this harm,” she says.

In order to foster the faith and minister to the faithful, Purvis says the church must divorce itself from celebrity culture, which is incompatible with the cross. “Celebrity points us away from the gospel and away from Christ,” she says.

This article also appears in the October 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 10, pages 30-35). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Header image: Pexels/Cottonbro

Add comment