My mom told me about an occasion when a devout evangelical woman first saw the religious images sprinkled about our home. “These are idols!” my mom’s friend exclaimed. My mom retorted something along the lines of, “Do you not have pictures of your parents in your house? Frames with graduation pictures? Photographs of people you love?”

I learned from a very early age that the statues in my house were not idols; they were reminders. The power of a reminder should never be understated, though. Such is the heart of the home altar: an intimate physical space for the spiritual remembrance of God.

Home altars trace back to the early church, what is often called Paleo-Christianity. The first Christians did not gather in basilicas or cathedrals, and the first Eucharists were not celebrated in carved altars under apses. Christianity saw its dawn in the dining rooms of houses and among loved ones. The remnants of what we call home altars can be traced to these house churches. Archeologists discovered in Dura-Europos (in what is Syria today) the earliest example of a house church. It contained third-century frescoes depicting Christ the Good Shepherd and other gospel stories. Art is, after all, a way to catch glimpses of God’s nature.

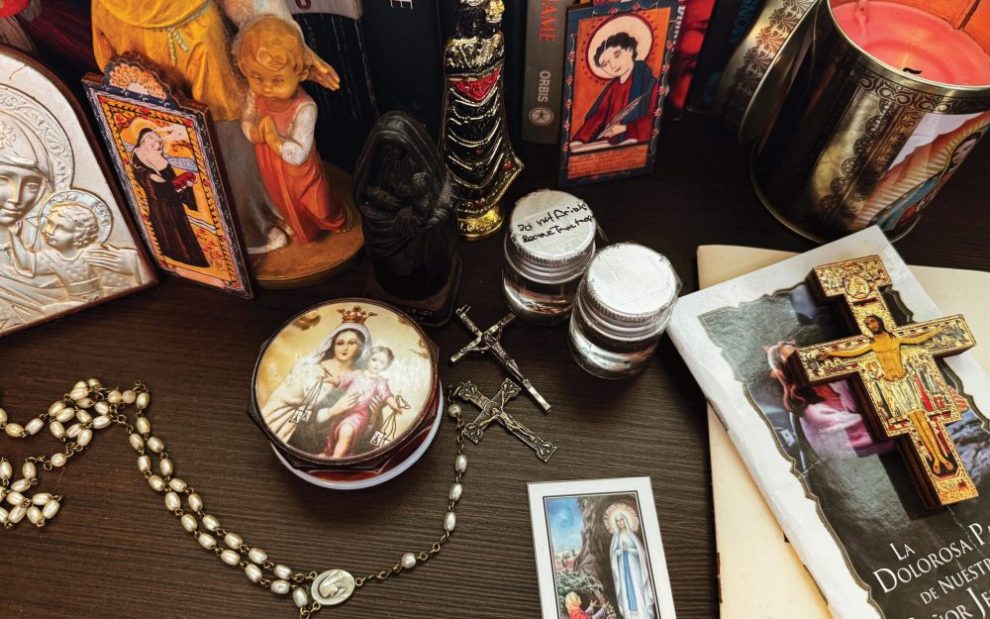

Devotional corners do not need to be elaborate. Throughout history, the common home altar has been a simple cross or crucifix. In some traditions, the cross is displayed in a manner that signifies the east, the direction of prayer. For Catholics, the crucifix is a powerful sacramental and a key element in prayers such as the Via Crucis or St. Francis’ prayer before a crucifix. The Catholic home altar can also be expanded to include other things, such as the family Bible, a relic, an icon, holy water, or blessed items.

In Latin American Catholicism, there is a huge emphasis on home altars, and they reflect a syncretism of Indigenous belief with colonial Spanish Catholic practices. It could also be said that these altars are a gendered practice: In an article for the Texas State Historical Association, the Tejana author Teresa Palomo Acosta says that “[women’s] maintenance of domestic altars has provided them a central, self-made role in worship, art, and culture by emphasizing an intimately based faith that strongly connects their daily lives with the sacred.” Altaristas (as these women are known in Spanish) reclaim some of the power lost to patriarchal church institutions. They honor their Indigenous heritage together with la Guadalupana, specific regional devotions, and pictures of family members.

Growing up in Central America, my family’s altars were not always obvious. The shelf that held sleeping St. Joseph in my grandmother’s living room was an altar, though I didn’t know it then. In my childhood bedroom, I had a corner of religious objects I was not allowed to get rid of—off-brand Precious Moments statues, a children’s Bible falling apart at the seams, and other memories of a hyper-religious childhood—even though I was well into my edgy anti-theist adolescence. Unknowingly, I begrudgingly made a corner for God, the only corner of my room in which God was allowed to reside.

My altars became intentional as I reached adulthood and reconciled with my Catholicism. I never viewed myself as an altarista, though; I feel like I lack the artistry of some women. For me, the corner of my bedroom is a disarray of objects, both religious by nature and utterly prosaic. However, while the exterior may be unkempt, things have an order and a reason in my head. I am a lifelong, profoundly anxious homebody. The unpredictability of the outside, its loud noises, crowds, and constant movement tend to cause me to have embarrassing meltdowns. So I shut the world out. The stagnancy of safety can feel like a curse, though, as if I were a prisoner of my own making. Amidst that lifelong struggle, home altars have delivered me.

When I look at my prayer altar in my bedroom, I see memories imbued with God’s presence. I have two small bottles of water from the river Jordan, brought to me by my dear friend Lydia. She lived in Jordan for a season and handed me these bottles when we met in real life for the first time. Lydia wrote on each lid of these bottles in black Sharpie: “DO NOT DRINK!!!” It makes me giggle to this day. These are not vials of holy water, but their connection to a person I treasure so dearly makes them divine in their own right.

My writing buddy, Madison, despite not being religious at all, gave me a wooden icon of St. John the Evangelist, the patron saint of writers. The prayer engraved on the back side of the statue echoes every conversation we have had, and I hold it dearly. It is a sign of true friendship and love I will never overlook.

On this same prayer altar, I have the Divino Niño statue my aunt bought on her last pilgrimage to Colombia before her cancer finished metastasizing. Next to it, I have a rosary from my great-grandmother that dates to the 1930s. It is made of traditional crumbled roses and miraculously still carries the slightest scent. A rosary my friend Silas gave me sits beside it. He used to sift through his Episcopal church’s secondhand knickknacks basket, and long before I made plans to go to Boston to visit him, he had found and kept a rosary for me. Alongside this rosary, Silas embroidered me a Magnificat patch to wear on my jacket. This rosary on my altar is a sign of trans joy and community love.

Finally, my altar has things you might consider bizarre, like my dead dog’s tag or Lady Gaga’s Joanne next to a CD player. People have said that my shelf is a junk shelf more than an altar, but I couldn’t disagree more.

Father Timothy Radcliffe writes that the spirituality of the home is not about elaborate rituals: The core of a home altar is not about fancy decor, shiny new icons, or even thematic adornments that match the liturgical year. It is about making room for God and looking for God in the abundant blessings you may already have.

One of my favorite contemporary spiritual authors is Episcopal priest and self-identifying “spiritual contrarian” Barbara Brown Taylor. In her words, I find a solace usually reserved for letters by medieval mystics. One of her books, An Altar in the World: A Geography of Faith (HarperOne), is about honoring the miracle of everyday life, understanding creation itself as an altar where one can encounter God in innumerable ways. The line between profane and sacred is nothing but a matter of perspective. Taylor encourages us to build little altars in our hearts or in the world around us so that we may commune with God in the unlikeliest places. Our lives, understood as beacons of love, community, and service, are altars of which we are priests.

For me, home altars remind me that God is among the little things and in the devotion between kindred souls. Souls I have been blessed to find, through time, space, and lifetimes, my fellow creators and lights of my life.

This article also appears in the September 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 9, pages 45-46). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Dani M. Jiménez

Add comment