“We are all called to be saints,” Dorothy Day is often quoted as saying, especially these days as the church considers her own canonization, “and we might as well get over our bourgeois fear of the name.” Less often related is that she would also have us get over our narrow churchy notions of what it means to be a saint.

In a 1946 editorial in the Catholic Worker, “Called to be Saints,” Day noted that the concept that all people are called to be saints was met with suspicion in Catholic circles. Today some bishops and academics lament that the Catholic Worker Movement has departed from the original Catholic vision of its founders, but in this editorial Day showed that there were many such critics from the beginning, and that much of their vitriol in those early days was directed at her. “In fact, so constantly these past 13 years of the paper’s existence,” she wrote, “charges of heresy are bandied back and forth.”

If Catholics largely ignored or condemned the Catholic Worker’s call in 1946 for all to be saints, Day rejoiced to find glimmers of hope that the idea was catching on elsewhere. This encouragement did not come from Day’s beloved Pope Pius XII in Rome, from Catholic theologians, or from the social encyclicals she studied, but from three decidedly non-Catholic novelists. “Now we are filled with encouragement these days,” she wrote, “to find that it is not only the Catholic Worker lay movement, but writers like Ignazio Silone, Aldous Huxley, and Arthur Koestler who are also crying aloud for a synthesis—the saint-revolutionist who would impel by his example, others to holiness.”

Day continued on to say, “Recognizing the difficulty of the aim, Silone has drawn pictures of touching fellowship with the lowly, the revolutionist living in voluntary poverty, in hunger and cold, in the stable, and depending on ‘personalist action’ to move the world. ‘Bread and Wine,’ ‘The Seed Beneath the Snow’ are filled with this message.”

Silone was a founding member of the Communist Party of Italy and one of its covert leaders during the Fascist regime. Expelled from the party due to his opposition to Joseph Stalin, Silone would later refer to himself as “a Socialist without a party, a Christian without a church.” Pietro Spina, the protagonist of the two novels that Day so admired, a “revolutionist living in voluntary poverty, in hunger and cold,” was a political exile who returned to Italy disguised as a Catholic priest to organize a revolt against the Fascist state. Pietro Spina’s rejection of the church into which he was baptized and his life outside its rules did not preclude him from being the archetype of the saint Day was convinced we are all called to be.

Another contemporary of Day’s, Arthur Koestler was a Hungarian-born Jew who, like Silone, left the Communist Party disillusioned by Stalinism. The saint-revolutionist that Day likely referenced was Nikolai Salmanovich Rubashov, the central character of Koestler’s 1941 novel Darkness at Noon. Rubashov was an old Bolshevik, not a believer, but one whose suffering and execution in a Soviet prison mirrored the suffering of Christ.

The English philosopher and novelist Aldous Huxley was not a Catholic either but was devoted to Vedantic (Hindu) philosophy, meditation, and vegetarianism. He is best known for his dystopian novel Brave New World, whose nonconformist protagonist Bernard Marx seems to be a saint-revolutionist who inspired Day, even though he took his own life in despair at the end of the novel.

Day found the saint-revolutionist synthesis not only in fictional characters but also in living secular social justice activists. In her 1964 eulogy for Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, secretary general of the Communist Party, USA, Day noted that the Ecumenical Council had stressed “this is the age of the laity” and that Gurley Flynn “always did what the laity is nowadays urged to do. She felt a responsibility to do all in her power in defense of the poor, to protect them against injustice and destitution.” In 1971, when Black communist activist Angela Davis was on trial for murder, Day insisted that “since Christ is our brother, Angela Davis is our sister, and we love and esteem her as such.” Day said of Davis, who was later exonerated: “All generations shall call her blessed.”

The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches:

The witnesses who have preceded us into the kingdom, especially those whom the church recognizes as saints, share in the living tradition of prayer by the example of their lives, the transmission of their writings, and their prayer today. . . . Their intercession is their most exalted service to God’s plan. We can and should ask them to intercede for us and for the whole world.

In all of her writing about the many saints she loved, Day never so clearly mirrored the official Catholic language as when she wrote of a saint who was not recognized by the church, a saint who had never been baptized or one who had never accepted Catholic doctrine and discipline. “There is no public figure who has more conformed his life to the life of Jesus Christ than Gandhi,” Day wrote in her column after Gandhi was martyred in 1948. “There is no man who has carried about him more consistently the aura of divinized humanity, who has added his sacrifice to the sacrifice of Christ, whose life has had a more fitting end than that of Gandhi. Truly he is one of those who has added his own sufferings to those of Christ, whose sacrifice and martyrdom will forever be offered to the Eternal Father as compensating for those things lacking in the Passion of Christ. In him we have a new intercessor with Christ; a modern Francis, a pacifist martyr.”

While her admonition is often interpreted as “all Christians are called to be saints,” Day’s intent was universal. Proclaiming that all are called to be saints, Day was not suggesting that all are called to be good Catholics or good Christians or even to believe in God. The saint-revolutionist synthesis, the personalist action that the world is even more urgently crying aloud for today, and the holiness that its example will impel in others have nothing to do with piety, religious confessions, or the sacraments. Its efficacy will not be measured or even perceived by the Vatican’s Dicastery for the Causes of Saints. As much as Day herself found her home in the church and strength in its sacraments, such considerations are not necessarily relevant to the revolutionary sanctity that Dorothy Day said that each person is called to.

“We are called to be saints, St. Paul said, and Peter Maurin called on us to make that kind of society where it was easier to be saints. Nothing less will work,” Day wrote in a 1958 appeal for funds. “Nothing less is powerful enough to combat war and the all-encroaching state.”

This article also appears in the November 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 11, pages 21-23). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

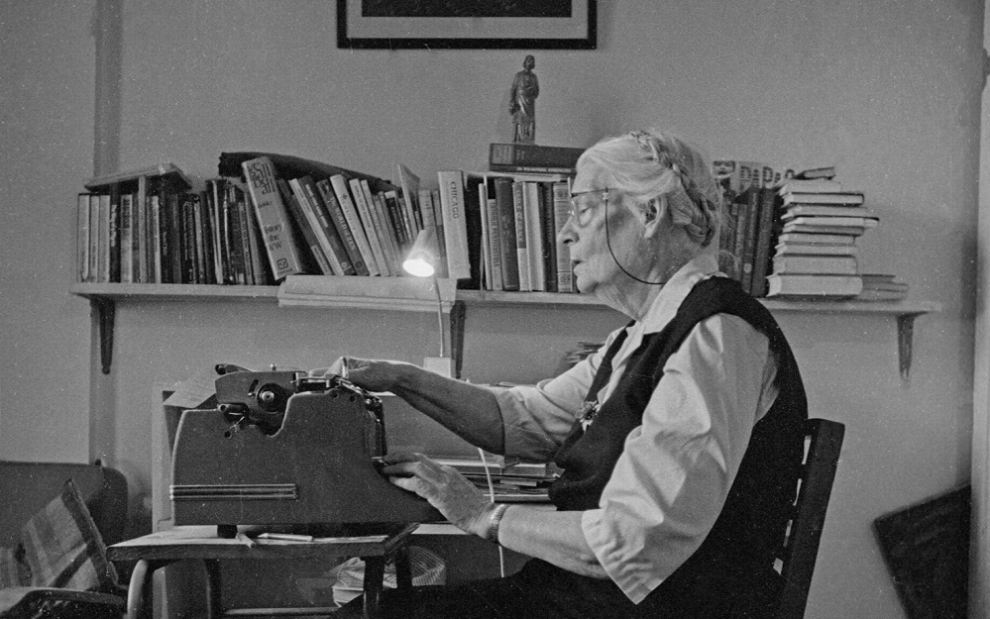

Image: Bob Fitch photography archive, ©Stanford University Libraries

Add comment