Catholic tradition likes the number seven. There are seven deadly sins, seven seals in the Book of Revelation, seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, seven days of creation in Genesis 1: It is a number signifying completion. Even the musician Prince, not Catholic but nominally Christian, captured this fixation in his 1992 song “7,” which has religious and apocalyptic overtones.

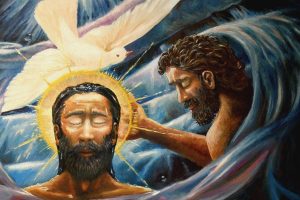

And, of course, Catholics have seven sacraments. But why seven? First, a sacrament is a visible, tangible, sign of an invisible and efficacious grace that is embedded in the ritual and liturgical life of the church. These rituals include sacraments of initiation–baptism, confirmation, Eucharist; sacraments of healing–penance, anointing of the sick; and sacraments of service–marriage, holy orders.

However, this understanding is based in a deeper theology of the sacramentality of all of God’s creation. Sacramentality means that God created everything as originally good and, therefore, all created things hold the possibility of communicating God’s presence to us, because they retain traces of the divine. The seven sacraments differ, however, in that they are distinct rituals that mediate God’s grace through ministers of Christ’s body for specific life situations and spiritual nourishment. We enter freely into a sacrament to encounter God and receive God’s free gift of self that the Catholic tradition has termed “grace.”

Historically, the number of sacraments fluctuated from as few as two to as many as 30 depending upon culture and context. After the 1054 Great Schism between Catholic and Orthodox Christians, the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) delineated seven sacraments. These seven were affirmed by the Council of Florence in 1439 and then reaffirmed and promulgated widely by the Council of Trent, which was called in the wake of the Protestant Reformation (1545–1563). It is because of Trent that the idea and practice of seven sacraments became standard and nonnegotiable throughout the Catholic world.

The 16th-century European Catholic Church was intent on reasserting and solidifying its own identity against the critiques and practices of various Protestant and Anabaptist reformers. For example, “mainline” reformers such as Martin Luther reduced the number of sacraments to what could be reasonably supported by scripture. For him there were three sacraments: baptism, the Lord’s table, and penance. For the radical reformers such as the Anabaptists, the precursors to today’s Mennonite and Quaker communities, there were no sacraments: They believed that the idea, rituals, and theology of sacraments could not be directly supported by evidence from the New Testament. Instead, they had “ordinances” such as the Lord’s table and adult baptism.

Today, there are only two sacraments or “ordinances” that all Christians agree upon: baptism and Eucharist. It seems not even Prince’s musical genius has been able to bring everyone to agreement.

This article also appears in the August 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 8, page 49). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Gary Yost

Add comment