Sarah is a new Catholic and joined the Catholic Church in 2020. (Sarah is uncomfortable using her last name in this story, as she hasn’t yet shared with many people that she converted from being Protestant.) She recently took her 4-year-old and 2-year-old to Mass at a nearby parish without her husband, who works weekends.

They arrived at Mass and found a pew in the back next to the shrine of the holy family. The children appreciated being next to statues of Jesus and Mary and, like many young kids, struggled to sit still. “They were trying not to be loud,” Sarah says. “But we were moving into the consecration, and the more sacred Mass is becoming, the more my stress is going up.”

As a visiting family she wasn’t sure if there was a cry room for her to move into. “The woman sitting next to us was making it clear with her body language that she was unhappy with what the kids were doing. She was scooting away from us and would look at us,” she says.

Sarah recalls that the woman looked at her family, narrowed her eyes, and scoffed while saying something underneath her breath. “I’ve never had someone do that at church before,” she says. “I felt so sad in that moment. I’m clearly trying hard, and it’s not good enough.”

She took to Twitter to voice her despair, writing, “We got a really nasty look at Mass today. Please know, I’m trying. I’m trying to instill reverence for the Mass in my children. I’m trying to do everything that is in my power to keep them quiet, every parent of little ones is trying. Please pray for us instead of scowling.”

Luckily, Sarah says her experience that day was more of an anomaly than the norm and that most adults are kind and encouraging. Yet, Sarah says, it’s been hard to find her place in the parish. The young adult ministry is mostly people just out of college, and the people in the women’s groups tend to be older. “I would love for kids to have community, but I would also love to have community,” she says.

When it comes to welcoming young parents and their children, parishes can sometimes struggle. Not only do many young parents, like Sarah, worry about their kids being loud or unruly during Mass, but it can also be hard to juggle feeding and changing babies during church, finding safe spaces for small children in parish buildings, and meeting the unique needs of each family. However, parishes can do some basic things to better welcome the youngest Catholics and their families.

A practical welcome

Statistics show that few people are attending Mass, and the number of people receiving the sacrament of baptism has declined over the years. According to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA), a research center affiliated with Georgetown University, infant baptism continues to decline steadily over the years, with 411,482 baptisms recorded in 2021 compared to 996,199 in 2000. With trends pointing to fewer families bringing their children to the Catholic Church, parishes must exercise creativity and innovation to help young families feel a sense of belonging in raising their children as Catholics.

“We should be engaging young families. Period. If we’re not, we’re kind of putting ourselves out of business,” says Edward Herrera, executive director of the Institute for Evangelization in the Archdiocese of Baltimore. Herrera has experience working in diocesan ministry as well as parish ministry and has five children of his own.

Herrera says parishes must create an environment where individuals can re-encounter the Lord.

“Do people have deep bonds of friendship with people in their pew?” he asks.

But even beyond social bonds, engaging young families also means attending to the particular needs of this demographic. Herrera mentions that parishes should think about welcoming new families the same way they would think about hosting them in their own homes. Months before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, he was working on a comprehensive list of things to consider when engaging young families at Mass. The list includes ideas such as:

- a drop-off zone near the doors for those who need extra assistance, whether they are young families or disabled people;

- bathrooms stocked with extra wipes and stools to make it easier to reach sinks;

- an indoor space where children can move freely;

- covered electrical outlets so toddlers cannot access them;

- and high chairs in gathering or social areas.

Two years into the pandemic, this also includes meeting people where they are when it comes to COVID-19, Herrera says. For example, some people may still be concerned about public spaces and choosing not to return to in-person liturgy. “You want to honor fears and concerns, but beyond that there is a segment within the church that has gone on with their lives,” Herrera says.

Hoon Choi, an assistant professor of world Christianity at Bellarmine University in Louisville, Kentucky, agrees with Herrera on the importance of providing young families with practical resources when they visit. He says it would be helpful for families to know even before setting foot in a church whether that parish is welcoming to young families, whether through a physical sign, something on the parish website, or a social media post.

In some instances, other Christian churches have worked to take an inclusive approach to welcoming families that could be a potential road map for Catholic parishes. For example, Fourth Presbyterian Church in Chicago has a page on its website titled “Children in Worship” that outlines where families can go during Sunday services if they need a quiet space for changing a diaper or if a child needs something in particular.

“I think the reality is that most families will look online for information rather than emailing or calling,” says Matt Helms, the associate pastor for children and family ministry at Fourth Presbyterian, via email. He says that Fourth Presbyterian is intentional about making its space a place where kids are welcomed and babies can cry. The ushers are always ready to welcome children and families with children’s bulletins and crayons. There is also a room set up where the service is streaming if parents need to step out with their child for a diaper change or feeding.

“It’s not always perfect, but if you are truly passionate about welcoming families, they will know,” says Helms, who has a 5-year-old and 2-year-old.

When asked what pieces really help young families feel welcome, Helms jokes that for the younger crowd it’s the toys in the Sunday School classrooms. “More importantly than [the toys], it’s the teacher or myself kneeling down in Sunday School, looking [kids] in the eyes, and inviting them to be a part of the room,” he says. “In worship, it is building a culture where little ones are appreciated for the joyful chaos they sometimes bring rather than seen as a barrier/detriment to worship.”

Embrace the noise

Choi says the Catholic Church needs a cultural shift to be more inclusive of small children. He and his wife have a 6-year-old son and 2-year-old daughter and attend a small Korean parish. When their children were a little younger, Choi and his wife would take turns nursing and feeding the children while his wife played the organ during Mass. It was always a balance.

Because of the size of their parish’s chapel, there was no place to nurse, so it happened at the back of the sanctuary. “While I agree we should push the church to be comfortable allowing women to nurse,” Choi says, “there also needs to be a cultural shift so mothers feel comfortable publicly nurturing and breastfeeding their children. We should not shame them.” He suggests that maybe an occasional announcement could be made from the pulpit or the priest could remind churchgoers of Matthew, Chapter 18, which says children are to be welcomed and invited to know Jesus, not be pushed away.

Choi knows that some in the Catholic tradition appreciate the reverence of high church liturgies where there are more periods of silence. But his idea of church includes more activity and more tears. “I love low church. I love the noise of the church,” Choi says. “I love the noise of the kids.”

One Sunday Choi’s son ran up to the altar during Mass despite attempts to keep him close.

“There are unspoken rigid rules about quietness during Mass, but for a 2-year-old it’s unnatural,” he says. “I completely support a kids’ room, if there are also churches with a kids-friendly Mass where loudness and nursing are welcomed.”

Choi’s comment acknowledges that different communities and families need different things to feel included. Louis Damani Jones, for example, looked for a parish with more space and a cry room for his daughter, who has a disability.

“We always try and make sure she’s comfortable,” says Jones. “It’s hard to sit in a place for a long time. I would ask myself, ‘Should I bring her? Is she enjoying this experience?’ . . . She deserves to be able to come. . . . That’s her expressing herself. She’s a child of God.”

Jones and his wife are raising a newborn, a 7-year-old, and a 10-year-old in St. Louis. Like Choi, he says that hearing the priest say children were welcome made a big difference in making young families feel welcome.

“The crying is nonstop,” Jones says. “The priest makes it known it’s a welcoming community. Comments are not welcome. The priest’s leadership is critical there.” Sometimes parents may feel inappropriate shame when their kids are loud, he says. “It takes the leadership (lay or priests) to welcome this—you shouldn’t feel ashamed.”

Making connections

Shirley Hart had two children under the age of 3 when she began feeling frustrated with her experience of attending Mass with little ones. Sometimes, when it came time for Mass on Sunday morning, it felt like she was holding her breath while church-hopping with her young family after relocating to Southern California. “[Sunday morning Mass] is the hardest hour of the week,” Hart says.

Hart finally settled into Mass at St. Bede the Venerable in La Cañada Flintridge, California. Her criteria for a family-friendly parish at the time was a short list: “I wanted a cry room, a priest that was not too scary, and a community that was welcoming,” she says. At St. Bede the Venerable, she liked what she heard from the pastor—the parish wasn’t a gas station where you stopped and filled up the tank when it was running empty, but rather it was an opportunity to linger.

She also found friendship with another mom while watching Mass from behind glass in a small chapel adjacent to the main sanctuary. Emily Hofer, who was pregnant with her youngest and had a 3-year-old in tow, felt the same struggle of dressing children, buckling them into car seats, and bringing them to Mass. “I met Emily in the cry room,” Hart says. “At the time we felt like we were the brave ones who were sticking to it.”

When someone asked them what they needed as young families, they responded that they wanted a sense of belonging and fellowship. They weren’t looking for child education programs: Hart and Hofer were working outside the home at the time and could not make daytime events.

“I was working 10 hours a day and couldn’t do it,” Hart says. “I wanted friends. I wanted to share our faith and raise our kids that way.”

They were asked by a former youth minister if they would help lead the young family ministry together. Things moved quickly as parish employees met them for coffee or dinner to talk through ideas. “It was nice to feel there was a lot of support here,” Hart says, including from the diocesan office.

Their first event was a potluck. From there they moved to events that involved inviting a speaker to come. When things got loud at family events, they knew they were in good company and that no one minded the commotion. “We are all in the same boat,” Hart says. “We can share knowledge and do fellowship.” Word got out about what the ministry at St. Bede the Venerable was doing, and families came with their little ones.

It takes a village

There aren’t necessarily one-size-fits-all approaches to welcoming young families given the diversity and complexity of the U.S. church. Some parishes, such as Choi’s, have smaller, almost chapel-like spaces, while others seat a thousand or more. Fiscal needs and physical space can also be a hindrance depending on the community. But physical limitations aside, many of the people interviewed for this article stressed that much of the onus of welcoming families fell on the pastor.

This reflects the teachings of Pope Francis in Amoris Laetitia (On Love in the Family), his 2016 apostolic exhortation on love and marriage. Within the text are references to the parish as a place that can help families and help them grow. A few passages even nod to seminarians’ formation as a holistic way of how future priests may approach the diversity of families in the pews.

“Parents make the effort to get their kids to church,” says Patrice Spirou, the ministry lead for family catechesis and curriculum in the Archdiocese of Atlanta. “A lot of younger pastors are open and understanding of family. . . . The church should be a place where families are affirmed and supported in the role.”

“If the pastor loves his people, the people know it,” Spirou says. “He doesn’t have to be perfect. If he loves the children, everyone knows that. It shows. It sets the tone. People know how to be comfortable.”

She notes that in her diocese the recent pastoral plan involved a strong vision of family ministry and family catechesis. Once the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, the diocese began to look closely at how to accompany families due to restrictions on Mass attendance and school closures. They created a free family-based catechetical program that parishes can opt into.

“We took the pandemic as an opportunity to pivot,” Spirou says. “Families said they wanted from their church an opportunity to strengthen their relationships within the family and through that their relationship with God.”

For Nichole Flores, a professor of religious studies at the University of Virginia, welcoming families includes things such as incorporating music at Mass that her son may hear during religious education sessions and ensuring there is a space set apart for families who have children with disabilities or babies who are crawling.

Flores has two toddlers and, like Sarah in the beginning of this article, has also experienced sadness when a woman seated near her family shushed her son in the middle of Mass. He was wiggling, and some around him wanted him to be quiet so they could have peaceful prayer time. In a deft move, her husband grabbed their son to take him outside the sanctuary while Flores started sobbing.

“This kiddo isn’t doing anything to try to annoy anyone—he is trying to be present at church too. He wants to joyfully worship. He wants to talk about Jesus, and loudly,” Flores says.

Thankfully, an older couple motioned her aside on her way back from receiving the Eucharist that day to give her kind encouragement. They were grandparents and explained they knew how hard it was for kids to sit still.

There is no family Mass option at her parish, and Flores isn’t sure they would attend another Mass time even if there was one given her family’s schedules. She also understands that there’s a need for all attending liturgy to be able to participate, including those who have a hard time hearing alongside the kids who want to be themselves.

“As parents it’s part of the sacrifices for the time being,” she says. “You have to give a lot of that up. When we are with kids it’s like a marathon—I’m sweaty.”

This article also appears in the December 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 12, pages 10-14). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

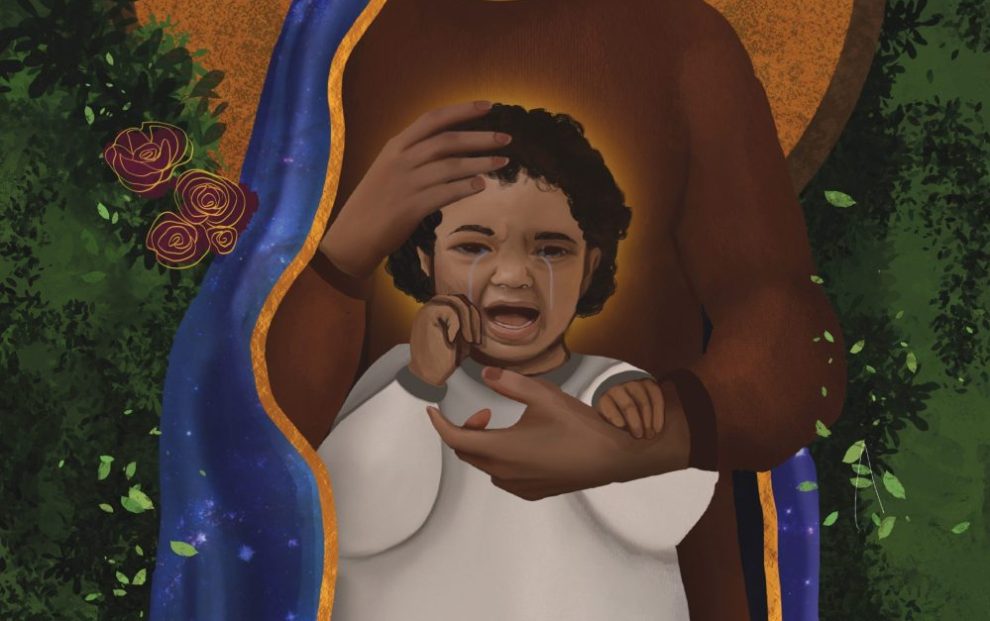

Image: Dani M. Jimenez/& her saints

Add comment