Most of us wear several hats in our many relationships. We may be children and parents and spouses simultaneously. We’re coworkers, neighbors, friends, and citizens, exercising these distinct roles all in a single day. We’re believers with convictions but also an openness to other points of view. Most of us are not just one thing. We play more than one role that’s of great concern to us. We don’t drop out of this constellation of identities when we actively engage one of them.

Among the primary roles I play are those of writer, public speaker, and catechist of the church. I don’t cease to be any of these while performing as another. In fact, it’s fundamentally as a catechist that I write and speak. My family members might even roll their eyes should you ask if I ever stop being a catechist for five minutes. Before I earned a certificate authorizing me to serve as a religious educator, I was in pursuit of the teachable moment in religious matters as early as the playground. I’d send my Protestant pals home with a rosary or take them on a tour of the stations of the cross around the parish church. How many childhood friends knelt beside me as I endeavored to explain the veneration of saints in front of some imposing statue? It’s a wonder, really, that I managed to have playmates at all.

After a lifetime of mutual fascination with mystical realities and the attempt to express them, I find myself asking another question that has until now eluded me: What is church teaching for? Surely this inquiry should have been engaged earlier in my work as a catechist. I’m ashamed to admit that not asking this question sooner has had inevitable consequences. Not only did I subject unwitting companions to lessons they may not have wanted. But even later, in religious settings where I was fulfilling a duty to present the faith, I doubtlessly taught what I myself had absorbed: that church teaching is spinach—necessary, nourishing, and not to be scraped off the plate just because you may not care for it.

Church teaching can be presented in many ways, not all constructive or useful. It can be a bludgeon to get miscreants in line. It can be wielded as a form of control, inciting fear, guilt, or dread. Think here of the “Great and Powerful Wizard of Oz.” When a voice that deep, threatening, and mysterious bellows from behind the curtain, spouting smoke and fire, it can be hard to do anything but kowtow. Many sit in pews or in classrooms hearing church leaders proclaim what’s what in just such a voice. Some of us buckle and obey. Others run for the exits.

I confess that initially I took my role as a catechist to mean I was to stand on a tower of soapboxes and shout religious truths until any conversation partners capitulated. Frankly, I didn’t know they were conversation partners. When the church speaks, what room is there for dialogue? Aren’t we just supposed to repent in dust and ashes?

Before too long, I realized carrots work better than sticks. I tried to entertain softer and more appealing methods of instruction. Wise mentors convinced me that humor is acceptable and storytelling is a must. A teaching might be offered as an invitation, not a dictate. A catechist might shine a helpful lantern on the road ahead rather than march the community forward at gunpoint. As odd as it may sound, church teaching might be viewed as kindly guidance on the journey, not a litany of rules laid down to stumble and ensnare.

I hope you’ve had pastors who used teaching in this gentler way. I hope homilists you’ve heard have beckoned more than barked. I hope your relationship to God and church has been shaped and sweetened by wisdom, discernment, and invitation. I really do hope your life in the church hasn’t been a long, abusive slog through commandments and pronouncements that seemed to gag you and take away your freedom. If you’ve suffered at the hands of your teachers and have not been aided in your quest for God and guidance, please let me apologize on behalf of the church.

It’s not supposed to be this way.

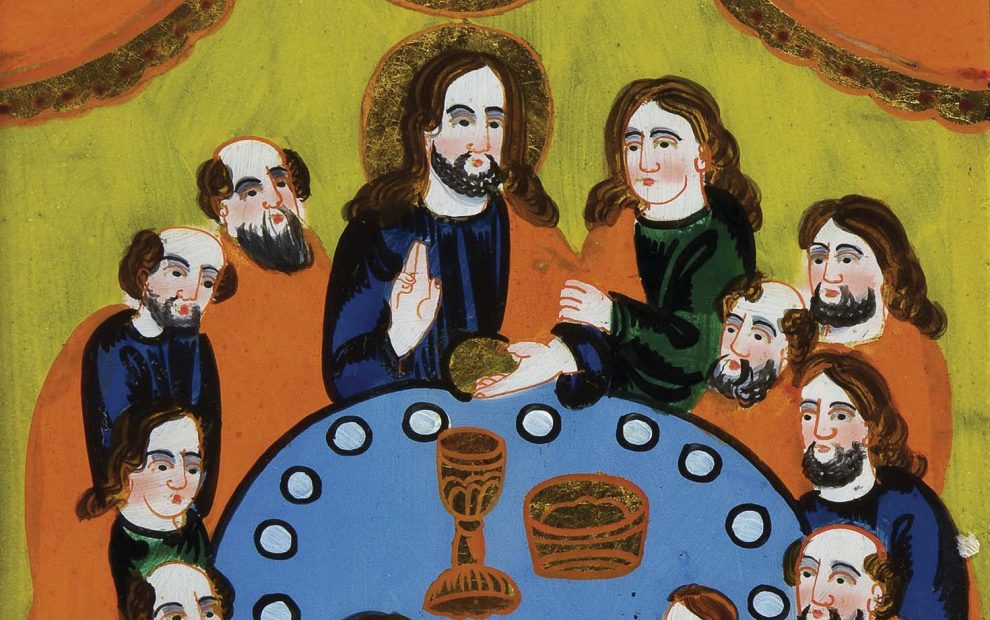

On the night before he dies, Jesus offers his friends the exact opposite approach. He gives them consolation. He urges them not to be afraid but to hold peace in their hearts. He invites them not to be troubled—even though immense trouble is right around the corner. Jesus doesn’t take this last opportunity at the table to lay down the law and get everyone in line. Rather, he supports and encourages: “My peace I give to you.” It’s a lovely example every teacher of the church should take to heart.

In the 2016 apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia (On Love in the Family), Pope Francis recommends something to parents in the task of handing on the faith to their children that I’ve turned over and over in my thoughts: “It is more important to start processes than to dominate spaces.” Most of us are used to authorities dominating the spaces they inhabit. Parents and pastors, principals and law enforcers, governors, supervisors, and, yes, even the lowly catechist are at least tempted to regard their role as one of seizing control and maintaining it by whatever means necessary. Even if you’re just running the weekly prayer meeting, the instinct to make things go the way you ordain them to happen is surprisingly compelling.

Yet if we don’t dominate the spaces over which we have authority, what else might we do? Pope Francis suggests we “start processes,” which is a much more conditional-sounding task. We start a process by asking a question and letting it hang in the air rather than shutting down conversation or curiosity by simply defining the answer and dusting off our hands. A process begins when we ask children why they behaved in a hurtful or unruly way rather than administering a quick smack and banishing them from the room. Pastoral care opens a process when we listen to why a marriage failed, why a person has been away from the sacraments for years, or why someone is alienated by an experience they’ve had in a religious setting. We opt to dominate the space when we merely tell people why their behavior is a violation of canon such-and-such and what the penalty will be for persisting on this path.

Some of us will find the open-endedness of process over the immutability of dominance to be uncomfortable. Dominating the religious space with doctrines and eternal truths is just so much easier to do! Whereas the way of process is, as the pope admits, a way to make our relationships and roles as parents or pastoral people “wonderfully complicated.” It’s also the way to make our encounters more real and honest. Choosing process over dominance doesn’t diminish the truth. It makes it more apparent and full of more possibilities than either party might have suspected from the start.

Because after all, what is church teaching for? Not to preserve some holy deposit of faith in a Vatican vault, untarnished by the ages. Teaching is meant to lead us into the overwhelmingly persuasive and compellingly attractive presence of a God who is all love and compassion. Dominating spaces doesn’t make the case for such a God. Inviting people to walk with us, however, just might.

This article also appears in the May 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 5, pages 47-49). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Add comment