My child was born at the dawn of a global pandemic. He doesn’t know a world without a pandemic, just as I don’t know what child care is like in “ordinary” time. Since the day my son was born, my spouse and I, both doctoral students burdened by our academic work as we discern and further our calling, have been struggling to find the not-so-often-found peace in this world of suffering and chaos.

Conventional childcare insights intending to divide or balance work and family only cause added frustration, for we can’t adequately plan for anything in this extraordinary time of pandemic. As we scramble to get enough supplies, do the laundry, secure a relatively stable living arrangement, and rush to respond as lovingly as we can to each of our son’s cries, a voice looms in our heads and unsettles every sign of peace: I am not doing any work. I can never get to my work!

But isn’t child care work? If you were to ask me, my instinctive answer would be yes. However, my frustration says something else. Only after much restless reflection, I realized that my struggle—shared by many—is rooted in conventional assumptions about work, its nature, meaning, and value. During the current pandemic, those assumptions are no longer viable if they were ever candid reflections of daily living.

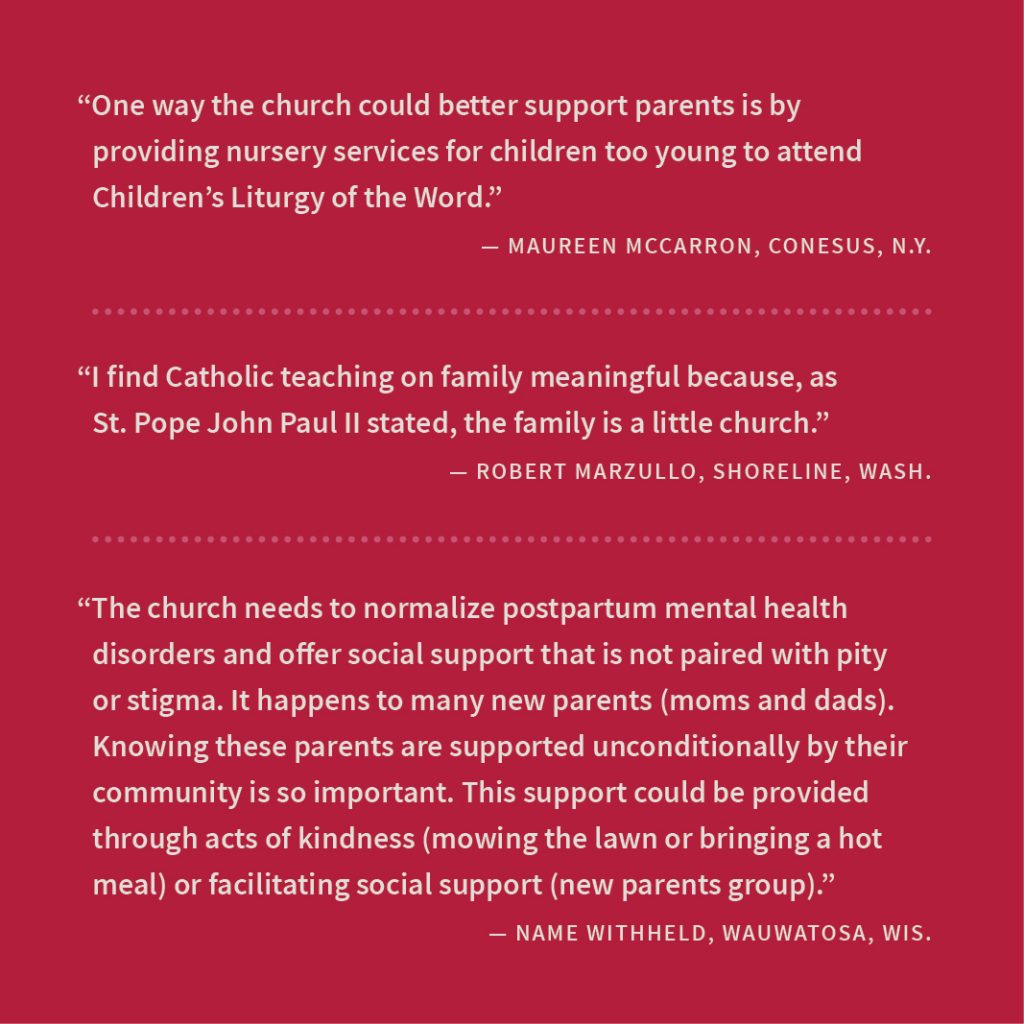

Almost 40 years have passed since St. Pope John Paul II articulated a theology of work in Laborem Exercens (On Human Work) and, in Familiaris Consortio (On the Family), called for a renewed theology of work that reflects the “fundamental bond between work and the family, and therefore the original and irreplaceable meaning of work in the home and in rearing children.”

However, what St. Pope John Paul II began 40 years ago still waits for its further and fuller development. His call for a renewed theology of work that binds work with family and respects the dignity and vocation of women and their work has yet to be fully realized. Our lived struggles to fulfill added child care responsibilities while remaining faithful and fruitful to our other vocations demand a theological reflection and reevaluation of our previous conceptions of work.

So the question remains: Isn’t child care work? The answer is definite according to the description of work in Laborem Exercens: Work is “any activity by man, whether manual or intellectual, whatever its nature or circumstances; it means any human activity that can and must be recognized as work, in the midst of all the many activities of which man is capable and to which he is predisposed by his very nature, by virtue of humanity itself.”

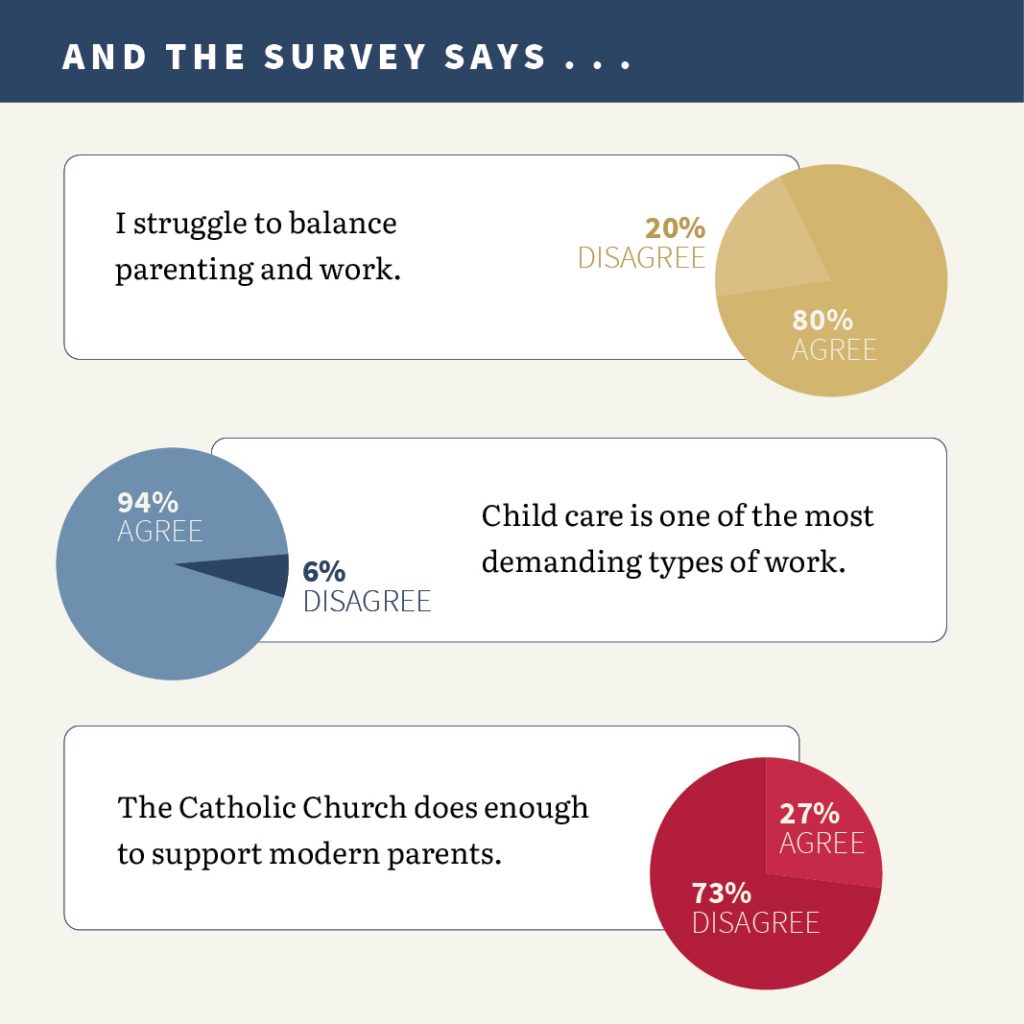

Not only is child care work—it is one of the most demanding types of work. The various mundane tasks such as cooking, feeding, cleaning, and teaching all serve to realize the humanity of the person. St. Pope John Paul II rightly stressed that as a foundation for the formation of family life, constitutive of human nature, the two spheres of work, the upkeep of family life and the education of children, must be united.

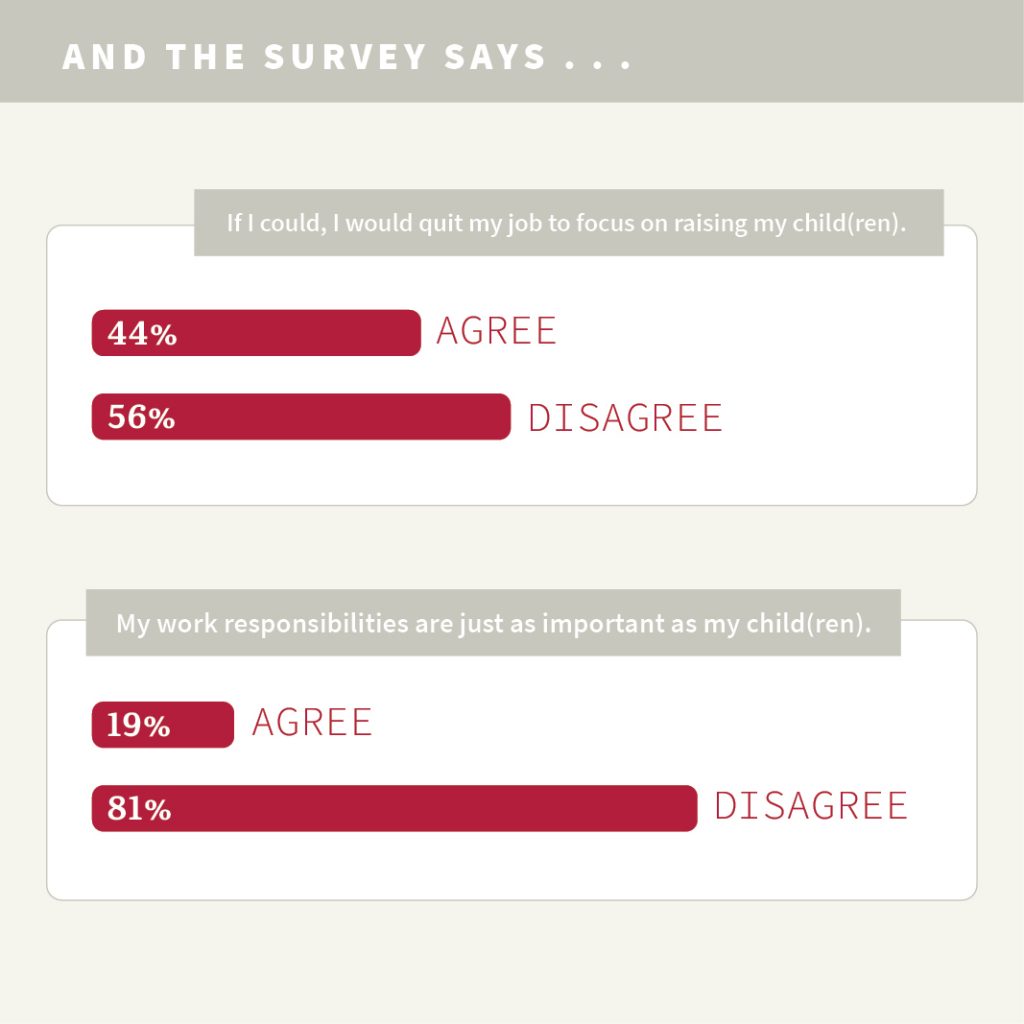

However, the current pandemic and our lived experience render apparent that the struggle to unify the work of child care in the home and the work of public apostolate remains for both spouses. If the conventional approach to work and family—assigning public work to the husband and child care work to the wife—can no longer guarantee our sanity, how else are we to find peace in our vocations?

After much restless searching, I have at last found peace in the ancient wisdom of Carmel, that is, to realize my “highest and most necessary vocation: Vivere Deo—to live for God.” St. Thérèse of Lisieux’s exclamation comes to mind. After feeling within her the multitude of vocations—Carmelite, spouse, mother, warrior, priest, apostle, doctor of the church, and martyr—she cried out, “Love comprised all vocations, that love was everything, that it embraced all times and places . . . my vocation, at last I have found it . . . my vocation is love!”

St. John of the Cross stated, “The soul that loves does not await the end of her labor but the end of her work. Her work is to love, and of this work, which is love, she awaits the end, which is the perfection and completeness of it.” To live for God is to love, which is the vocation of all vocations and the end of all works.

For me, frustration about productivity (or lack thereof) was rooted in a misunderstanding of work and the end of work as love. While there is no doubt that my academic work aiming to further the development of moral theology in the church can only be guided by the love of God, the divine face is even more apparent and immediate when I gaze into the face of my son, who is the fruit of the sacraments graced by God.

If the end of work is to live for God, completely and totally, and to have every act become love in union with God, then the only thing I should concern myself with is to strive toward the state where I can say, in the words of St. John of the Cross in the Spiritual Canticle, “Now I occupy my soul and all my energy in his service; I no longer tend the herd, nor have I any other work.”

All my work—whether it is reading, writing, and meeting with colleagues or doing laundry, washing dishes, and sitting with my son while he plays—is driven by love. Regardless of what I do, I am now in a state of unceasing prayer. My multitude of works are a manifestation of my singular vocation—to love. I shall become like Brother Lawrence of the Resurrection and be content with any place and any task.

Image: Unsplash/Charles Deluvio

Add comment