My cousin’s an evangelical Protestant. Recently he told me the rousing story of how he came to Christ. After a neglected childhood and perilous young adulthood, he stumbled into a prayer service and encountered the Christian story in a way that felt powerful and irrefutable. “I accepted the work that was done on the cross of Calvary,” he concluded reverently.

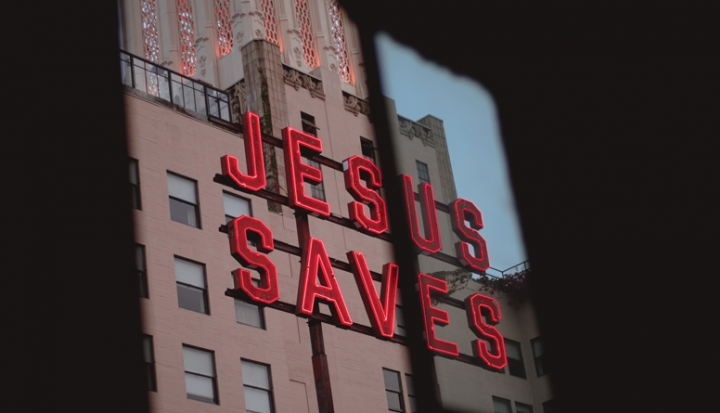

Next, of course, it was my turn to deliver a come-to-Jesus moment. And like many cradle Catholics, I don’t really have one. Nor am I entirely at ease with the formulaic phrases that are the bona fides of evangelical faith. “Coming to Christ,” “accepting the work,” “being saved,” those sorts of things are as peculiar expressions to me as ritual dialogues of the Mass sound to someone not accustomed to liturgy. Both Christians, my cousin and I speak the same language—but with a different dialect. Sometimes the dialect is so thick that it makes communication obscure.

The French have a phrase: l’esprit de l’escalier—the spirit of the stairs. It refers to the conversation we continue to have with someone in our heads after we’ve departed the room and head downstairs. In my staircase conversation with my cousin, I’m explaining to him that I’ve come closer to Jesus, not just once but in several significant episodes of my life. Have I delivered myself wholesale at any of them? It seems brash to suggest this.

Perhaps this is one distinction between Catholics and evangelicals: our comfort level in making broad claims about the depth of our surrender. We Romans have imbibed far too many lessons about the virtue of meekness to ever admit we’ve clutched Jesus for good and for all. Those repeated confessions of ours have taught us how fragile our intentions are.

“But it’s not about what you’ve done or can do,” the cousin-in-my-mind insists. “The work has already been done for you on the cross!”

Yes, I accept this too—but in my Catholic translation of what this means, which isn’t quite what my cousin is suggesting. We’ve returned to that stubborn old theological quagmire: faith vs. works. The classic and very simplified argument is that Christians of the Reformation view salvation as a matter of faith: Jesus supplies it, we trust it. This makes saying the right words to seal the deal both powerful and necessary.

Catholics view the grace supplied by baptism as equally effective for salvation. The sacramental ritual is indeed powerful and essential. But we’re less passive going forward. Anyone raised Catholic knows we’re expected to account for every drop of grace we get by producing a hearty crop of good works.

Like many Catholics, I’m prepared to say I’ve both come to Christ and am still on my way. I acknowledge the divine rescue achieved by Christ’s cross and claimed in baptism. My cooperation remains crucial—a word rooted in cross—for such a gift not to be squandered.

This kind of conversation remains in my head. It would make both my cousin and me uneasy. I realize I’m not using the words he associates with a real deal, once-and-for-all conversion to Christ. And he’s not addressing the process of deepening growth that, for me, has come to signify the greater consequence of divine encounter.

At the same time, I’m being grossly unfair to my cousin and to evangelicals everywhere. Because he and they are not at odds with my demands for process and widening purpose. My cousin is, in fact, a sterling example of discipleship. Because of his own early misadventures, he has made a career of mentoring wayward teenagers. He sacrificed a lifetime of higher earnings for the sake of making a difference to at-risk youth. Not only that, but after raising their own children, he and his wife adopted a second set of kids in need of a stable home.

Stacked against my meager social accomplishments, you might well judge my cousin’s life the better imitation of Christ—all of which makes this grievous impasse in our conversation so troublesome. He and I are playing for the same team. Yet we view each other with some suspicion when it comes to the way we talk about God and the mechanics of “being saved.”

It’s enough to make you wonder if the words even matter.

When talking about God’s saving activity, from Moses to Jesus to you and me, do some formulas come closer to saying it right? Are there ways to get it seriously wrong? Do our Jewish friends express something wholly deficient when they pray fervently to the “God who saves” but don’t acknowledge Jesus as Savior? Am I less saved if it makes me anxious to testify that I’ve been saved when that pamphlet-clutching stranger rings my doorbell and asks? Is verbal testimony vital to faith at all or beside the point? Is it possible to rely too much on logging sacraments in church and not enough on public witness?

Catholics can’t point fingers at the careful preference of other Christians for a precisely articulated formula of faith. Every line of our creed was fashioned in blood. Each dogma and doctrine has been argued over and fought for—and some died for.

It would be thoughtless and superficial in this generation to say who really cares about all the archaic phrases and to question if it makes a difference what we say. It has mattered too much in the past for it to matter too little now.

But the nagging question persists: Hasn’t enough blood been shed over words and theological constructs? Might we stand accused one day of honoring fine phrases and formulas more than we valued people?

At the same time we must consider what happens to meaning when language is watered down to the agreeable point of compromise. How is truth endangered when we claim as little as possible so as to offend no one who may see things differently?

If we abandon God-language altogether to formulate a broadly favorable social morality based on values, what essential components are we losing?

St. Paul was proud to claim at the end of his life: “I have kept the faith” (2 Tim. 4:7). We can be sure he didn’t mean creeds and formulas. Paul cherished his allegiance to the risen Lord and to the spread of his gospel and paid a deep personal cost for this fidelity.

Words did matter to Paul: He was a cautious formulator of just the right ones to get his meaning across. He built the church across Asia Minor on the elegant architecture of theological constructs he fashioned in real time.

Yet across decades of letters, Paul drops some themes and embraces new ones, changes his emphasis, and adopts various methods—in short, he exercises a remarkable flexibility in “keeping the faith.”

Paul was learning, just as we all are, that keeping the faith means different things in different circumstances. To Paul, no one is expendable, not Jews or Greeks, women or men, masters or slaves. That made it essential not to write anyone out of the script of salvation or to define the formula too narrowly.

Keeping the faith is something we believers strive to do. Giving it away is just as vital. But we can’t do the second if keeping the faith means nailing it to the floor. God may well define divine realities slightly wider than the most perfect creed. Some good old Catholic humility might serve us well here.

This article also appears in the October 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 10, pages 47–49). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash cc via Jason Betz

Add comment