Billed as an “oasis in the desert,” Holy Cross Retreat Center in the Mesilla Valley south of Las Cruces, New Mexico, hosts retreats, provides spiritual direction, and sponsors an annual arts festival. The retreat center also offers some of its rooms to people facing various life challenges, including chemotherapy patients at the nearby university hospital. The center’s mission statement states, “The Gospel and St. Francis of Assisi call us to welcome those in spiritual or physical need.”

During the first administration of President Donald Trump, Holy Cross’ director decided their generosity should extend to undocumented people seeking what some people would call “sanctuary,” but what the center refers to as “Franciscan hospitality.” Over the years, their guests have included a mother and her 6-year-old child after they were threatened with deportation, a Mexican journalist facing death threats for his work, a group of Venezuelans, and an asylum-seeking Colombian father and his U.S.-born son.

Today, Conventual Franciscan Father Tom Smith is still open to providing shelter to migrants who feel threatened, especially given the current administration’s policies of mass deportations without due process and the threat of being sent to prisons and camps in dangerous foreign countries. But he is also aware of the increased risks on his part.

“I think it’s our responsibility as Catholics to accept the risks of some of our ministries. When there is an injustice, we need to respond,” Smith says. “The risks are higher now, no question about that. And yet my contention that we are called to care for one another is still there.”

Smith is unique in his willingness to talk publicly about his ministry. Today, religious groups providing safe shelter to people face retribution from the government or law enforcement and are often doing so under the radar, fearful of an increasingly authoritarian federal government not afraid to punish those who disagree with its policies. One activist said lawyers had advised that their organization not use the term sanctuary.

Best known thanks to movie depictions of criminals rushing into dark churches to evade capture, the centuries-old practice of providing sanctuary has a rich history in the Judeo-Christian tradition, although it has morphed over the centuries to adapt to needs of the time. Those who have studied or practiced sanctuary say it is at the heart of the gospel and urgently needs to be reclaimed in order to respond to the anti-immigrant policies in the United States today.

Bishop Mark Seitz of El Paso, Texas, a leader in ministry to migrants and refugees, admits that the traditional practice of sheltering in church buildings may not be the best way to respond to today’s mass deportations, which could affect as many as 13 million people. But the history of offering care to people fleeing is an essential church teaching, he said in a lecture at Loyola University in May.

“The core perception is this: The obligation to provide mutual aid and care for the displaced is constitutive of what it means to be a eucharistic community. And that has to be true at the grassroots level, at the level of individual Christian communities,” he said. “As [Pope] Benedict XVI put it, ‘A Eucharist which does not pass over into the concrete practice of love is intrinsically fragmented.’ ”

Ancient roots

In the most famous scene of Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, set in the 15th century, Quasimodo swings down from Paris’ Notre-Dame Cathedral to rescue the Roma street dancer Esmerelda from the gallows by whisking her inside the church, crying, “Sanctuary! Sanctuary!” But the idea of refuge for criminals in sacred spaces predates medieval Europe—and even Christianity.

In Judaism, the first record of the right of asylum in a sacred space is in 1 Kings, when Adonijah seeks safety from his brother and his rival, Solomon. The Talmud identifies six cities of refuge where perpetrators of accidental killings could escape blood vengeance. Greek and Roman temples and shrines also offered protection to those fleeing persecution, debt, or slavery. Earlier tribal societies had similar traditions.

Rather than distance themselves from those practices, Christians embraced them and even claimed their churches offered stronger protection than pagan temples. By the fourth century, the church had formally adopted sanctuary, in part as a repudiation of Roman punishments of execution or enslavement, which Augustine saw as cutting off the opportunity for reconciliation and redemption from sin.

But sanctuary in medieval times was not a simple “get out of jail free” card. Instead, it tried to restore a moral balance with required penitential practices and, in most cases, exile or banishment (an irony, since the modern sanctuary movement involves protecting people from deportation). In medieval times, if criminals seeking sanctuary were not Catholic, they were expected to convert.

“Sanctuary presents itself as precisely the site where the wrongdoer can come into the protection of the church and be expected to engage in the penitential discipline necessary to reconcile the wrongdoer and the wronged,” says Karl Shoemaker, a professor of history and law at the University of Wisconsin and author of Sanctuary and Crime in the Middle Ages, 400–1500 (Fordham University Press).

In contrast to more contemporary practices of sanctuary, which seek to offer protection for the innocent from overreaches of state power, the ancient practice of sanctuary was intended to protect those who were guilty, usually people who had committed murder or theft. Pursuers could not enter the church to capture a criminal, but fugitives also could not bring a weapon inside the church to attack others or defend themselves.

In the Middle Ages, rulers honored sanctuary to signal their respect for the power of the church, although breaches of sanctuary did occur. Perhaps the most famous example is that of Thomas Becket, who was murdered in Canterbury Cathedral.

“There was a fairly robust agreement on the part of secular and ecclesial authorities that sanctuary was to be respected,” Shoemaker says. “When someone really wanted to blacken the character of a king or ruler, they would show the person violating sanctuary. This is a very consistent trope throughout the medieval period.”

Similarly, the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) for decades maintained a policy that required immigration officials to refrain from entering so-called “sensitive locations” such as churches, schools, and hospitals. Under President Joe Biden, protected areas were expanded and strengthened. In January, the Trump administration rescinded these protections.

Five days after this policy changed, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents arrested a Honduran asylum-seeker outside the Pentecostal church he had helped found in suburban Atlanta. The Iglesia Fuente de Vida had installed locks to prevent immigration raids in the church, but ICE lured him outside by buzzing the ankle bracelet he was required to wear until his asylum court hearing. Other congregations have moved to making gatherings more secretive, and many churches in immigrant communities have seen plummeting attendance at religious services.

After a group of religious organizations, led by Quakers, sued DHS, a judge in Maryland temporarily blocked immigration raids in some places of worship in February, citing the First Amendment. Several Christian groups have filed similar suits in federal court since then, with Georgetown University Law Center’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection representing the plaintiffs in one case.

The U.S. bishops’ conference did not join these lawsuits, although they pushed back on the administration’s move in a statement with the heads of Catholic Charities USA and the Catholic Health Association. “We recognize the need for just immigration enforcement and affirm the government’s obligation to carry it out in a targeted, proportional, and humane way,” the statement said. “However, non-emergency immigration enforcement in schools, places of worship, social service agencies, healthcare facilities, or other sensitive settings where people receive essential services would be contrary to the common good.”

Bishop Alberto Rojas of San Bernardino, California—himself an immigrant from Mexico—condemned the growing immigration enforcement in Southern California in June after ICE detained multiple people in the parking lot of one church and took a parishioner into custody at another. “It should be no surprise that this is creating a tremendous amount of fear, confusion and anxiety for many,” he said in a statement in late June. “It is not of the Gospel of Jesus Christ—which guides us in all that we do.”

Two weeks later, after ICE apprehended people on the property of two Catholic churches in the diocese, Bishop Rojas made the extraordinary move of lifting the obligation to attend Mass for those who fear immigration enforcement there. Other bishops and clergy in Southern California have begun showing up at immigration court hearings. They say no one has been detained or deported while they were present.

Some lawyers say immigrants are safer in their own homes, where law enforcement must have a signed warrant to make an arrest, than they are in public spaces, including churches. But sanctuary has, even from the beginning, been less about legal protection than a moral resistance against secular authority, Shoemaker says.

The Reformation and the Enlightenment, as well as the expanded jurisdiction of the modern state, led to the restriction of sanctuary laws and eventually their abolishment in England in 1624.

What remained—and eventually would be resurrected in U.S. contexts—is the idea of sanctuary as the “protection of people who are perceived as friendless and helpless against an all-powerful state apparatus,” Shoemaker says.

On July 28, several religious groups, including Baptists, Quakers, and Lutherans, brought a lawsuit against Secretary of Homeland Security Kristi Noem over the Trump administration’s decision to rescind a policy discouraging immigration raids at houses of worship. As of early August, this was the fourth such suit to be brought on the question of arrests made at so-called “sensitive locations.”

A theology of sanctuary

In 1999, Rosa Robles Loreto came to the United States from northern Mexico and became a valued member of the community in Tuscon, Arizona. She was a volunteer at her two sons’ school, for their Little League teams, and at Santa Monica Parish. In 2010, a traffic stop triggered her deportation because she had overstayed her visa, which she unsuccessfully fought through the courts for four years. On the day she was to be deported, Loreto sought sanctuary in Southside Presbyterian Church, where she ended up living for 15 months before the U.S. government agreed to allow her to stay in the country.

Although Loreto is Catholic, she was only able to find sanctuary in a Protestant church (although then-Bishop Gerald Kincanas visited her weekly). That prompted theologian Leo Guardado, who worked with migrants in the area and who himself emigrated from El Salvador at age 9 with his mother because of the country’s civil war, to question why a practice and concept that used to be at the very heart of Catholicism seemed to be fading.

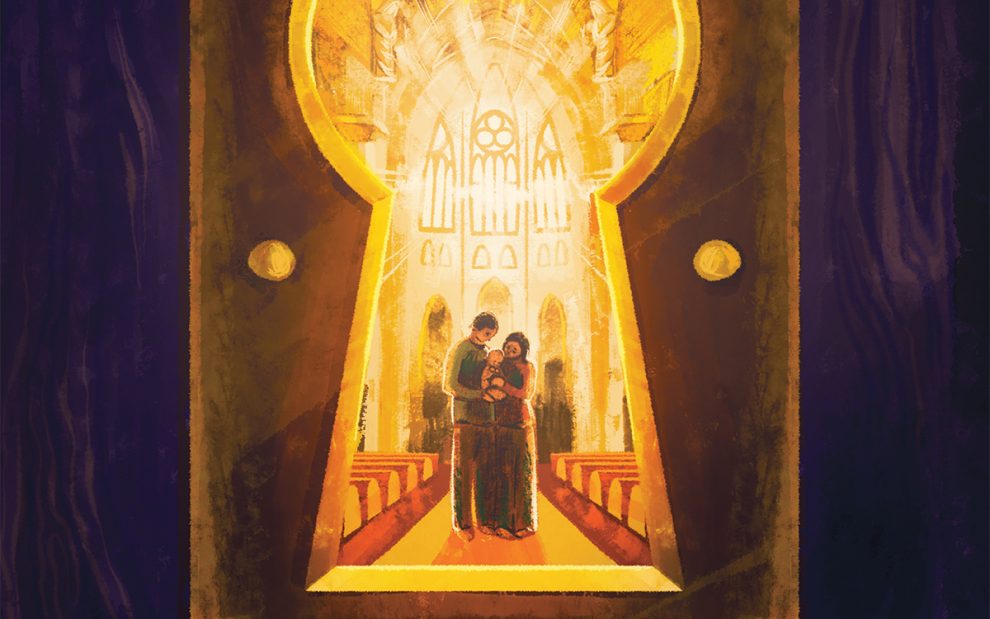

“To encounter the displaced other is to encounter the mystery of God,” says Guardado, now assistant professor of theology at Fordham University. “That’s where God becomes incarnate in history. When people take refuge in churches, there is something of the holy that is unleashed.”

In his book, Church as Sanctuary (Orbis Books), Guardado traces the history of the practice as a creative response to people threatened by generalized or state violence and argues that the church should not reject the tradition, especially in a time of massive forced displacement. He believes it’s no accident that people historically have sought refuge at the altar or baptismal font, as these powerful symbols indicate that sanctuary is a sacramental action.

“The early bishops understood that this was more than a political or social action,” he says. “This was tied to sacramentality, where God’s presence is and is made manifest through the protection of people.”

That spatial dimension of sanctuary—literally in the sanctuary of a church—also highlights a unity of liturgy and social action, when a place usually associated with prayer and devotion becomes a site of the work of justice, Guardado says. “Doing the work of the reign of God is not just something that happens ‘out there.’ ”

Sanctuary also must happen in a community, he says. “It’s not just about being within the walls of the church, but it’s about the community of people who protect and journey with them. That kind of holy encounter has the capacity to reframe faith as a whole.”

Guardado is not advocating for a return to a legal right of sanctuary, which existed before the separation of church and state. But he does believe sanctuary should be reinserted into the Code of Canon Law so that parishes can draw on the tradition to discern if they want to consider offering asylum.

The earlier version of the Code, written in 1917, said that a “church enjoys the right of asylum, and those who flee there may not be extracted, other than in the case of necessity, without the permission of the [bishop], or else the rector of the church.” But in the 1970s, two Vatican commissions studied the issue and disagreed about whether churches were still necessary as sanctuaries in the modern world. Some thought embassies had supplanted churches in offering such protection.

No decision was made, and the section on sanctuary disappeared from the revised code in 1983. Sanctuary is not prohibited, but it’s no longer mentioned. This happened, ironically, just as the sanctuary movement was emerging in the United States in the 1980s.

Guardado is hopeful that Pope Leo XIV, who has a doctorate in canon law, might recodify what his predecessor, Pope Francis, preached and prioritized: a theology of sanctuary, especially for the 300 million migrants worldwide. “Law is powerful,” he says. “If it isn’t codified, it’s optional. But that which is legally codified will last for centuries.”

Sanctuary in the United States

In June, President Trump deployed the military to Los Angeles against largely peaceful protesters who opposed ICE abductions of undocumented workers. The clash highlighted a feud between the administration and “sanctuary cities,” jurisdictions that refuse to cooperate in federal immigration enforcement and offer something of a safe space, much like the ancient Jewish “cities of refuge.” The administration has repeatedly tried to punish sanctuary cities by denying federal funding (later ruled to be unconstitutional) and “outing” such areas with public lists.

Attempts to provide safe spaces for various groups goes back to the Underground Railroad, which could be seen as an early example of providing sanctuary in the United States. Some churches—primarily Black churches and Quakers—served as places of safe harbor for enslaved people seeking freedom. But these churches held no legal right of sanctuary and were in fact defying the Fugitive Slave Law, which criminalized harboring runaway slaves.

Some churches also used the term sanctuary when helping young men who were trying to avoid the military draft during the Vietnam War in the 1960s and ’70s, but again they did not have legal protection. In 1971, Christ the King Parish in San Diego allowed nine sailors from the USS Constellation, which was to set sail to Vietnam, to claim sanctuary. Although federal marshals arrested the servicemen, they were all eventually able to avoid being dishonorably discharged from the Navy.

But it was the 1980s “Sanctuary Movement,” as it called itself, that became the most visible example of churches working to provide protection, in this case to migrants fleeing political violence in El Salvador, Guatemala, and other parts of Central America. Because the Ronald Reagan administration had supported counterrevolutionaries in these countries, asylum-seekers were blocked from entry and threatened with deportation if they did make it to the United States.

Catholics and other Christians were inspired to respond by liberation theology as well as the murder of Salvadoran Archbishop Óscar Romero, three American nuns—Maura Clarke, Ita Ford, Dorothy Kazel—and Jean Donovan, a lay missionary. In 1982, six churches—Southside Presbyterian Church in Tucson, Arizona and University Lutheran Chapel, St. John’s Presbyterian, St. Joseph the Worker, St. Mark’s Episcopal, and Trinity Methodist near San Francisco—publicly declared that they would provide sanctuary for Central Americans. Hundreds of churches and other organizations would eventually join the movement.

The majority of churches in the 1980s Sanctuary Movement were mainline Protestant, a demographic reality that continues today. Most sanctuary churches were also predominantly white, prompting some to criticize paternalism in the movement, as well as a failure to respect the expertise and agency of those it claimed to serve.

In the beginning, the Sanctuary Movement’s goal was to save lives by preventing deportation, but it led to some sanctuary-seekers essentially becoming incarcerated in churches for months or even years. The movement also worked toward changing government policy, succeeding in 1990 when the George H. W. Bush administration halted automatic deportations of Salvadoran and Guatemalan asylum-seekers.

A “New Sanctuary Movement” arose during the Barack Obama and first Trump administrations. One woman, Edith Espinal, who had come from Mexico as a teenager, spent more than three years in sanctuary in an Ohio Mennonite church building after receiving an order of deportation while seeking asylum. She was eventually granted protection for three years under the Biden administration.

For many people working with migrants today, limiting sanctuary to offering safety inside a church building is too narrow. Faith in Action, formerly PICO National Network, has worked with congregations to address issues of injustice locally and nationally since the 1970s. The more than 1,000 congregations in their network provide know-your-rights trainings, accompaniment to court-ordered check-ins, as well as material and spiritual support to those threatened with deportation.

“Sanctuary is also being publicly vocal and pushing back on what’s happening in the country right now,” says Omar Angel Perez, director of Faith in Action’s immigration justice program. “That’s part of sanctuary work.”

He praises faith communities, such as those providing a calming influence during the Los Angeles protests, for “showing up” and even “putting their bodies on the line and taking risks with public action.”

St. Joseph Sister Suzanne Jabro of the San Diego-based organization Border Compassion notes that women religious have been involved in ministry to migrants throughout history. She uses the term radical compassion to describe the organization’s ministry to migrants who need food, shelter, clothing, or legal representation.

Although its tagline is “Compassion knows no borders,” that doesn’t mean the group supports so-called “open borders” or has no respect for national boundaries. But they rail against depersonalizing migrants and believe as Christians they should provide care and solidarity. “We’re about protecting the vulnerable and loving our neighbors without distinction,” Jabro says. “I guess that makes it rather radical.”

Dylan Corbett of Hope Border Institute, a Texas-based organization that works for justice at the U.S.-Mexico border, believes the church is called to accompaniment and hospitality during today’s marginalization of migrants.

“That may require sanctuary,” he says, or an ecclesial community’s action may look different. But Christians cannot look away.

“We cannot remain indifferent before the suffering of our brothers and sisters,” Corbett says. “This is a moment of trial for the immigrant community in the United States. We have to take action to be in effective solidarity with them. It’s part and parcel of who we are as people of faith.”

This article also appears in the October 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 10, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Ryan McQuade

Add comment