Immigrants today experience economic, social, legal, and pyschological crucifixions.

Last April I was working on a video documentary on the U.S.-Mexican border. It was Holy Week. Each day I talked with undocumented immigrants, church workers, coyote smugglers, and border patrol agents, trying to capture something of the complex and painful drama of illegal immigration.

On one occasion in southern California near the border, I came upon two agents parked in their Ford Bronco trucks. They seemed ready to trounce on any trespassing immigrants like lions waiting for their prey. I asked if I could take a few camera shots. A bit surprised, one agent replied, "And who are you?"

I said, "I teach at a university and am a Catholic priest."

"A priest?" he sneered. "My, you certainly have had a field day in the news recently."

I shot back, "Well, your group hasn't been doing too badly either. You just granted visas to the two terrorists who slammed planes into the World Trade Center-six months after the event!" I resisted being boxed into his stereotypes, but our exchange also made me reflect on how quickly we typecast others based on the mistakes of a few.

Undocumented Latino immigrants, perhaps more than any other group in the United States today, feel the acute sting of dehumanizing stereotypes. They are often labeled as illegal aliens, wetbacks, spits, drug dealers, gang leaders, or even terrorists (although most of the terrorists, ironically, have come in through legal visas). While some regard immigrants as a threat, the U.S. economy would simply shut down without them. They are often the ones who wash dishes, cut grass, build houses, serve in hotels, harvest crops, and work in factories.

"I didn't want to come to the United States," says Maria Jimenez from Jalisco, Mexico. "I simply got to the point where my family struggled to buy sugar, eggs, and tortillas. When we could no longer afford even these, I had to leave home." Her journey, like that of many other immigrants, starts with poverty. Her search for basic human necessities landed her in an immigration detention center, far removed from her family. Typecast now as an "illegal alien" and a "criminal," she experiences cultural displacement compounded by the searing loneliness that goes with living as a stranger in a foreign land and leaving family behind.

Roberto Gallegos works in the freezer of a meat-packing plant all day; he lives with the fear that every day at work may be his last, knowing that he can be deported at any moment.

Ana Ortega stayed behind in Oaxaca, Mexico, and she and her six children have not heard from their husband and father since he left eight months ago. They don't know if he is alive or dead but fear that he may have become one of the thousands of desperate immigrants who have been dying crossing the deserts, mountains, and canals. In recent years, on average, more than one immigrant a day has perished trying to enter this country, dying to work for a job that no one else wants, except the desperate.

Beyond the complex political and economic factors of immigration, deeper spiritual issues challenge us. Undocumented immigrants today experience nothing short of a contemporary Way of the Cross-an economic, social, legal, and psychological crucifixion that often dehumanizes them and not infrequently robs them of their human dignity, if not their very lives.

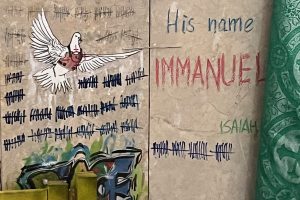

But immigration is not simply about the movement of people from one country to another. It is also about a mindset, an attitude, a way of looking at people who are "different." Border control is not simply about protecting us from harm but about isolating us from each other. It is about building not simply walls of concrete but walls in our minds and hearts that separate us from recognizing in the stranger a common humanity, a human dignity, a presence of Christ.

Within the particular stories of immigrants and their hunger, thirst, estrangement, nakedness, sickness, and imprisonment, we can see the face of a crucified Christ (Matt. 25:31-46). My experience with immigrants teaches me that the face of Jesus, in whom we shall one day read our judgment, already mysteriously gazes on us. We encounter him especially through the poor, who, like the faces of undocumented immigrants, challenge us to welcome them with new eyes.

This article appeared in the April 2003 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 68. No. 4, page 50).

Add comment