O little town of Bethlehem,

how still we see thee lie!

Above thy deep and dreamless sleep

the silent stars go by.

Missing from the famous carol’s description are Bethlehem’s four or more sushi restaurants. The “little town of Bethlehem” has grown to be a mid-sized city with its own suburbs. Tempting as it is to think of Christ’s birthplace as its Disneyfied Christmas-card version, American Catholics should pause this holiday season to consider Bethlehem as it is now, because while the carol may not feature the sushi joints, it rightly describes:

Yet in thy dark streets shineth

the everlasting light;

the hopes and fears of all the years

are met in thee tonight.

In October, I spent a day in Bethlehem, as one of the few tourists to visit since the Israel-Hamas war began two years prior. The light I saw there shone not only from Bethlehem’s streets, but from its people—as it does from all people. Over 2,000 years ago Jesus was born in Bethlehem not only to be the “everlasting light,” but to show us how to see that same light in all God’s creation.

Whatever value the perspective of a one-day visitor may have in discussing one of the world’s most storied cities in the midst of one of the world’s most intractable, brutal conflicts, this is mine: a stranger, caught between worlds even at home, willing to listen and learn. I was baptized Presbyterian, attended a Greek Orthodox school for six years, converted to Catholicism in high school, and married a Jew. My husband is a progressive Jewish peace activist—not a rare breed, but a much maligned one—and I sit in the chasm with him between our fellow Americans who downplay the humanity of Israelis or of Palestinians.

My tour company arranged for an Arab-Israeli driver to take me to my guide’s house. All the way from the hotel, I clutched my passport tightly, expecting to be searched at gunpoint by Israeli authorities. But the bored IDF draftees waved us through the wall dividing Jewish and Arab territory, euphemistically called ‘the security barrier.’

The overwhelming impression of Israeli state power in the West Bank is a long, slow, bureaucratic series of humiliations against the people living there. This is to say nothing of the extensive violence by Israeli settlers against Palestinians.

When we picture Mary and Joseph’s journey to Bethlehem, it’s easy to forget that even though they were returning to an ancestral home, they were traveling through occupied territory—territory held directly by the Romans or ruled by their puppet king Herod. Whatever the details, their journey was probably not just physically taxing, especially for a heavily pregnant woman, but laced with anxiety. Did they worry about catching the attention of Roman forces?

My guide for the day was the energetic Khadra Zreneh, a Christian, who welcomed me graciously into her home. Khadra lives in Beit Jala, one of Bethlehem’s suburbs, which has been a hub of Christian life for centuries. Nicholas of Myra—yes, Santa Claus himself—also lived in Beit Jala, where a church now sits over his cave hermitage.

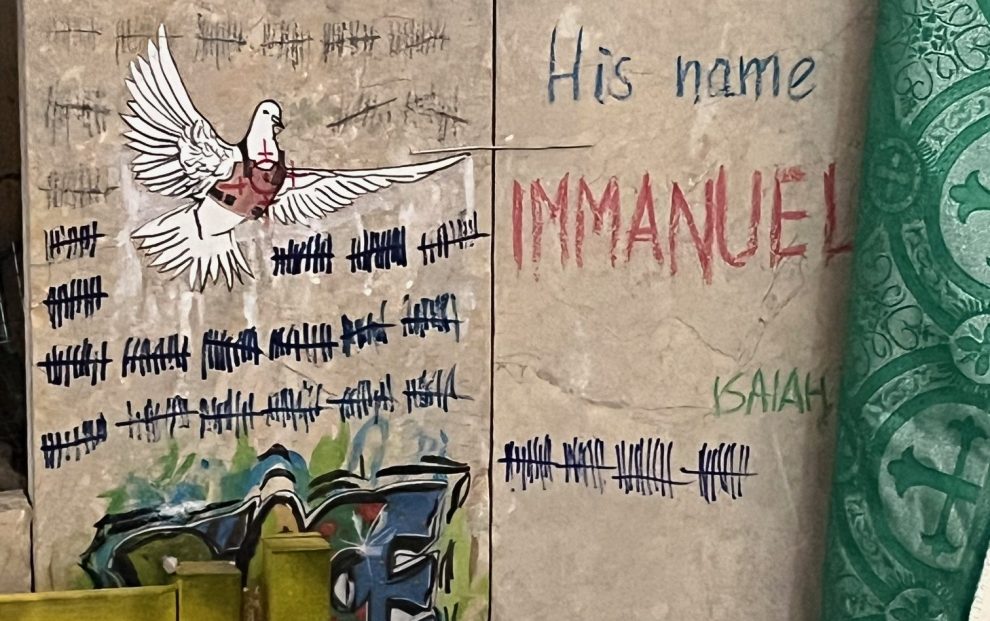

The Cremisan Monastery sits perched on a hill overlooking its vineyards, and atop its own legal troubles. Despite a ruling by Israel’s Supreme Court that Israeli seizure of the monastery’s lands is illegal, the government continues its plans to build the wall right through the vineyard. The construction will also displace 58 Palestinian Christian farming families. Inside the monastery chapel, the altar is decorated as if it were the security barrier—graffiti on concrete panels. On one, a dove flies, caught in the crosshairs. Another proclaims from Isaiah: “His name—Immanuel.”

Across the valley, an illegal settlement rises on the opposite hill. Near the monastery there was an event venue that once had boasted a commanding view—until Israeli authorities insisted that the owners make the fence opaque for nonspecific security reasons. One strongly suspects the real reason was that Palestinians are not entitled to nice views, or that settlers did not want to be reminded that Palestinians are people who have weddings and birthday parties just like they do. Life goes on under occupation, with the threat of force always in the background—just as in Jesus’ day when Jewish festivals were still celebrated, though under strict Roman watch.

“I am happy to live in peace with these people,” Khadra says, gesturing at the far hill.

“Do you think they are willing to live in peace with you?” I ask. We both agree it is unlikely. Khadra and I speak about our dismay in the face of the war. She tells me of a Jewish Israeli friend—one she cannot visit because of restrictions on Palestinian movement—who has lost loved ones in the war.

“What do you say?” Khadra asks. I know the question well. I tell her of a Palestinian-American acquaintance, one of the first people to check on my husband and me after October 7—yet I, in my cowardice, have no idea what to say after so much horror in her home country. It is an unease I carry with me to the Church of the Nativity.

Every old house in the Old City of Bethlehem is partially subterranean, carved into the white stone the city sits on. The stable where the holy family sheltered is identified with one room in an underground cave dwelling, now the Grotto under the Church of the Nativity. The white chalk stone has turned black from 1,900 years of lamp, candle, and incense smoke. Khadra and I are among a handful in what is normally a packed space, sitting next to the Catholic-administered Altar of the Manger. Overhead is a glass star lit by electricity. It is profoundly peaceful.

Yet I am aware the peace and uncrowded quiet I feel in this little cave is possible only because of the war—because of the fear that keeps travelers away, a fear experienced so sharply by the people of Bethlehem day-by-day. Further out, children in Ukraine and Sudan and a thousand other places cling to their mothers in fear.

If we see Bethlehem only as the twee town of Christmas carols, we fail to understand the town not only as it is today but as it truly was at the nativity. The Pax Romana Jesus was born into was a peace built on domination, not justice and dignity. Is not the world outside the cave the day I visited—the world of war, of self-aggrandizing tyrants, of tax levies that crush the poor—the same as the one the Prince of Peace came into?

Here in this cave, as the hymn intones, are met the hopes and fears of all the years.

Outside the Church of the Nativity, there is a row of empty craftsmen’s shops. Browsing the wares at an olivewood carver’s store, I feel a tug on my sleeve. It is the fourth generation of the family business—a daughter, about six—who previously offered a bottle of water. This time, she hands me an olivewood heart. It warms my own heart in the moment and for the rest of the day, but it is only in sitting down to write that I realize this little girl, playing in her father’s carpentry shop, echoes what the Christ child did in this land twenty centuries ago.

The light shines in Bethlehem, as when the herald angels proclaimed peace to people of good will (Luke 2:14). When talking about this conflict, or any conflict, it is essential to remember that human beings—like the carpenter’s daughter—are at risk.

That is not a solution to this conflict, only a good-faith starting point. When I return home, friends and family ask me for my perspective. I tell them I cannot provide a solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict, but that any solution will require all parties to forgo their claims to perfect justice—even, for most people, their claims to good-enough justice—for family homes destroyed, loved ones killed or detained or taken hostage.

It is easy enough to tell people to forsake revenge, but justice? “But that’s impossible,” one person tells me, speaking for the rest. “That’s not human nature.” True, but we must work for peace, keeping in mind the angel Gabriel’s words that begin the Christmas story: “Nothing will be impossible with God” (Luke 1:37).

A familiar earthly light now shines in Bethlehem as well; the city has lit its Christmas tree in Manger Square for the first time since the beginning of the war two years ago. I message Khadra to express my joy. She asks me “to tell people to come [to Bethlehem] and that they are [most] welcome.”

This Christmastide, pray for the people of Bethlehem—and may their stories, so imperfectly told here, help you think of the city as not just a place far away and long ago, but a vibrant place full of living souls. May that help you welcome the Prince of Peace into your hearts this season not only as a child, but a living presence that demands you work for the peace of all people.

Images: Courtesy of Allison R. Shely

Add comment