For nearly a decade, Peter Walker has spent the majority of his time in the great cathedrals of England. The Church of England has been experiencing a steady decline in attendance since the 1960s, before Walker was born. Yet, when Walker is stationed in a church, members of the public congregate, forming lines around these great stone buildings that have stood for centuries.

Walker is not an orator, bishop, or priest; rather, he is a fine artist who works primarily with sculpture and painting. For the last decade, he has been the trusted artist of the Church of England, bringing contemporary art and light displays to over 30 UK cathedrals through his company, Luxmuralis.

Luxmuralis is an artistic collaboration between Walker and composer David Harper. As a team, they specialize in immersive fine art, light, and sound installations across the UK and abroad. They also explore Christianity’s tradition of fine art through new media and contemporary art production. Their art reflects the changing sensibilities of congregants in a digitally connected world without disrupting the life and sanctity of the church space and its congregation.

While Walker and Harper are unique in how they approach their work with churches, they are not the only ones incorporating technology into religious art. Many artists are using contemporary means and art forms—from lightwork to artificial intelligence—to illuminate churches and breathe new life into Christian architecture through modern artistic expression.

Some critics of digital art in religious spaces worry that without regulation or a sense of reverence for a space’s sacredness, digital art will overpower or denigrate not only the beauty of these spaces but also their sanctity.

However, for some churches, utilizing digital artwork offers a genuine opportunity to evangelize in a world with an ever-shifting sense of what’s beautiful, good, and true. Although these installations draw crowds, they are not simply about putting bodies in seats or money in coffers. If done with intention, digital art displays can highlight aspects of a church’s edifice that patrons never noticed before, allowing them to both experience it anew and, in some cases, embark on a unique spiritual journey.

A “new Renaissance”

Wherever Walker and Harper’s music, light, color, and art can be found, so too can the people whom the Church of England has been longing to get back in the door, in the pews, and back to a relationship with God.

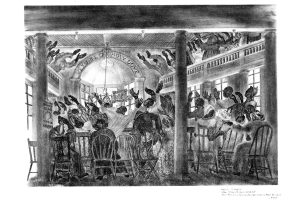

Walker’s exhibits are experimental in color, shape, and movement. Other multimedia installations offer a multisensory display, primarily focusing on light mapping, which draws attention to the intricate details and symbolism within the church that might otherwise go unnoticed.

While the various artists and installations have different styles, Luxmuralis, the Aura Experience, and their counterparts not only help viewers see churches through a new lens but also allow them to be fully immersed in the art: The viewer becomes a part of a living, breathing painting and thus steps into a more active role as they become more deeply integrated into the sacred space itself.

Walker refers to the growing use of technology and new media in art as a “new Renaissance.” Churches that have stood for centuries across North America and Europe are incorporating digital artwork into their liturgies as a means to get people through the door, with hopes that they will be inspired to come back or stay in the pews.

The Diocese of Turin is currently sponsoring a digital display of the Shroud of Turin that is traveling around Europe, bringing a pilgrimage to the holy relic directly to the people. In the Notre-Dame Basilica of Montréal, tourists buy tickets for the Aura Experience, a light mapping projection project created by Moment Factory that traces the architecture and highlights the cultural heritage of the Canadian landmark. In Serbia, art historian and curator at the National Museum of Serbia in Belgrade Ivana Lemcool is working to digitally insert fragments of church architecture and artwork into the interiors of Eastern Orthodox Christian churches to reflect how they once looked before aging or destruction.

Art reflecting architecture

Walker grew up in a working-class family in midland England, where art and creative endeavors weren’t readily accessible. As a child growing up in the UK in the 1970s to ’80s, Walker says he experienced a societal migration away from the church. Apart from sending him to Catholic school, his family was not church-oriented.

As an adult, Walker fell in love with the arts through literature and became a successful sculptor and artist. Despite his limited background with the church, he began collaborating with the Church of England 10 years ago, when the dean of the Lichfield Cathedral approached Walker to do a seven-year residency and to serve as an artistic director.

“He basically said, ‘Look, I want to reinvent visual art in a cathedral. We can’t connect with certain audiences, visitors, or pilgrims—we’re getting a certain demographic, and it’s getting older, so how do we bring these people in?’ ” Walker says.

Walker’s big art installations that include both light and sound allow him to explore subjects that are difficult to capture statically or inertly. Before performing at a new church setting, Walker creates individual digital fine art paintings using light while Harper composes the music. When they arrive at the space, they recompose and recalibrate what they have to fit the particular structure, sometimes creating bespoke works that utilize the entirety of the building from the sanctuary to the nave, the transepts to the choir loft.

“As you walk around in certain cathedrals, you are essentially following in the footsteps of 1,000 years of history,” Walker says. “People have walked on those routes for hundreds of years.” He says that following in these historical footsteps while looking at new artwork allows even longtime congregants to see a church building in a new and profound way: “Having something contemporary in there allows you to be present in that space again.”

Every person will view his work in cathedrals differently, Walker says; all individuals bring their own thoughts and emotions, and all are walking their own spiritual paths when they enter into the space.

In 2017, Luxmuralis created an exhibit called Life based on the book of Genesis. Rather than overtly using the biblical story about creation in seven days, however, Walker says they designed the exhibit to represent 24 hours on Earth.

“Using this framing allowed us to look at multiple different levels of what creation was, never diluting the power or the sentiment, but inviting it in such a way that allowed people to sort of stand there, be present, to take in the beauty of and especially within that space,” Walker says.

In addition to light and sound, Walker and Harper’s work also includes other—sometimes more traditional—mediums, though with a contemporary approach. When he started Luxmuralis, Walker says they wanted to “create the stained-glass windows of our time.” He points out that stained-glass windows, also once a new and radical medium, have never simply been beautiful colored glass that captures light. On the contrary, created during a time when many people couldn’t read, these windows tell profound visual stories without words.

“With digital art, we’re able to tell those stories to people in a way that relates to them, in a place where those stories should be told,” Walker says. “We created this style where you’re in the paintings as they move around you, and you’re within these beautiful stories. So rather than painting the architecture, the art fits within the architecture hand in glove, and it bleeds and breathes and rotates and moves within it. It’s a very powerful and quite all-encompassing experience.”

An ancient tradition

The long-term intertwining of church and art reveals that embracing revolutionary art forms is not new.

“Everything we see as ancient and venerable was new once,” says Liz Lev, a Rome-based art historian. She points out that while we now see things such as Gothic cathedrals as the pinnacle of this ancient art tradition, people would have been skeptical about them, too, when they were originally built—around 1200 C.E.

“Art has moments where it makes these great leaps into new media,” she says. “Michelangelo once dismissed oil painting as something that was for old men, women, and Germans; yet, if we had all listened to Michelangelo, we wouldn’t have Caravaggio. There is a certain amount of embracing new techniques, new technologies, that we need to be open to.”

Walker says the church has always had art at its core. However, ancient art forms that were once new and of their time, such as frescos, can be difficult for the average modern observer to fully understand or engage with as the artist once intended.

Father JJ Mech, rector of the Most Blessed Sacrament Cathedral in downtown Detroit, points out that the church has introduced new inventions and ideas throughout the ages to “level up” our encounters with Christ in the liturgy.

“Why wouldn’t we use every quality visual opportunity that is dignified, every beautiful opportunity, everything that we smell, taste, and hear, and have to be able to elevate us to connect with God?” he asks.

Mech points out that for most of the church’s history, there were no sound systems to ensure people could hear the priest. Instead, people figured out how to build pulpits surrounded by a shell that allowed the sound to carry and for people to hear better. “If we don’t grasp these opportunities, we will always be hungry,” he says. “We need to be able to offer new ways to reach God to people who need it.”

Utilizing technology responsibly can help create a “rebirth,” both in the church and in the field of artistic expression, Walker says. The majority of people are connected to technology all the time through their phones—why not draw people out of their world of personal technology into one that they can share with others in community?

“The way we actually experience life now is so different to every generation before us,” he says. “It is really important that, as an artist, as a priest, as whatever background you are from, you look at the world in front of you and see how people are consuming that world, because it is very difficult to stop the tidal wave moving forward.”

Walker also points out that the hunger for something deeper is universal. “Everybody needs something spiritual,” he says. But while some people might find meaning in an ancient practice such as the Liturgy of the Hours, these traditions won’t resonate for everyone.

For Walker, digital artwork is a way of reaching people where they are—of talking to them in their native language. “It enfranchises people, allowing them access to what they may not reach out for on their own,” he says. Even if people just enter a church to see the artwork, not for any overtly spiritual reason, “it gives them a translation of what an experience in a sacred space is.”

The dignity of a church

Mech has made it his mission to turn the Archdiocese of Detroit’s Cathedral into an apostolic center of arts and culture, with the ultimate goal of attracting people of all walks of life and faith to the Catholic Church.

Over the years, he has added a Marian Grotto, a relics tour, and a bee garden. He has rescued art from the basements and attics of the archdiocese, hanging it on the walls of the cathedral and parish center. Each aspect is meant to serve as a “shallow entry point,” encouraging people to walk through the door and then to stay.

An artist himself with a background in architecture, Mech has been advocating for the diocese to bring a display to the cathedral similar to the Aura Project in Montréal. He sees it as a logical continuation of the church’s mission to support beauty, truth, and evangelization through the arts.

However, despite his support of the arts overall, Mech cautions that any new installation—especially digital art—must be done mindfully to preserve the church’s sacred space and identity.

“We have all been to liturgies where things have been distracting or things were done that didn’t seem reverent,” he says. He cautions that churches have to be careful. “We want to ensure the dignity of the liturgy and of a sacred space.”

Mech adds that implementing new technology and art forms into the liturgy should never be done simply for the sake of modernization. On the flip side, however, the church should never reject modern technology simply because it doesn’t have a thousand-year history.

“We have to take the best, which is from God. That’s where the good is, and that’s what engages us,” Mech says. “When you go into a church building, it should engage you, it should include you. You should know what you are feeling and why you are feeling it, and you walk away different. Good liturgy elevates us, which is what good technology can do—it is a sanctifying encounter.”

Art historian Lev also points out both the possibilities and challenges of all art, including digital art. To ensure the art upholds and enhances the sacredness of a space, she cautions that the artists embracing these new technologies must first never lose their sense of Catholic identity. Artists need to be wary of letting a new technique rule them instead of the artist mastering it and using it for the glorification of God.

“Ours is an incarnational religion,” Lev says. “God did not come as a hologram, God did not come as a computer program, and God also didn’t show up in 2025 via the technology of whatever huge tech company is doing something. God showed up in person and was physically present in the world with people touching God’s wounds, as a baby with people picking him up.”

For Lev, the danger is that the wonders of new technology such as AI could cause us to lose sight of the wonders of the incarnation. Art cannot be about showing off the new, cool thing; it’s about reflecting the fact that the Word became flesh.

“It’s not a question of fear of this new technology; it is a question of maintaining our identity as Christians who are enchanted, amazed, and in wonder at the incarnation,” she says. “If there is a way that AI can participate in that, great. But if AI is going to take the lead on that, then [that becomes a problem].”

Making churches accessible

For many people coming to see Walker’s installations, it is their first time in a church for decades—or maybe ever. Walker and his team have the privilege of observing people take in the installations; they overhear conversations and sometimes chat with the visitors themselves.

Sometimes, visitors don’t know what to do when they walk into a sacred space, or they think it is not for them because they don’t understand the art or rituals, Walker says. Because technology is something that everyone has access to, bringing it to churches in the form of art can help make the church feel more accessible to visitors.

“We’ve had over a million people in the UK come to our installations, and a lot of those people will report back that they’ve had spiritual encounters,” Walker says. “They’ve returned to the church. They say, ‘I’ve never been in this building that’s five minutes away from me, and now it’s a place I want to return to.’ ”

For Walker, this points to an important part of art’s purpose. “It’s profoundly important for all cathedrals and churches to look at the digital world, best practices, and what they want to achieve with it, and for that to be part of the future journey of how these spaces are used,” he says. “Contemporary art gives people the fantastic opportunity to be in these places and experience the subjects, the discourse, and the power of art in a way that they can consume and understand.”

This article also appears in the December 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 12, pages 10-14). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

All art created by Luxmuralis

Add comment