Arriving to the United States as a teenage undocumented migrant—a refugee from his native El Salvador—Auxiliary Bishop Evelio Menjivar-Ayala of Washington, D.C. proceeded along the path taken by most immigrants: night school to learn English, hard work in multiple jobs, paying taxes, and eventually seeking and earning U.S. citizenship.

Menjivar-Ayala says he felt a calling to serve God and the church from an early age. As a child in a devout, impoverished family, he witnessed the U.S.-backed military regime’s violence against the dispossessed and how they targeted the Catholic Church for defending people. By the time the country’s 12-year armed conflict ended in 1992, the government and paramilitary forces had killed nearly two dozen Catholic priests, four nuns, and hundreds of catechists, including three American nuns and a lay missionary working with them. In 1980, just days after Archbishop Óscar Romero called for an end to government repression, an assassin gunned him down while he was saying Mass.

Menjivar-Ayala was ordained a priest in 2004 and appointed Auxiliary Bishop of Washington in December 2022 by Pope Francis. In this interview, he speaks of his experience as a refugee from violence and how Catholics should act toward the strangers among us. He also holds out hope that the church will be guided by Catholic social teachings and become an outward-looking, prophetic church that accompanies the poor and the vulnerable in our world today.

You were born in 1970 in El Salvador. What was your childhood like?

I was born in a canton—a village—called Carasque, in Nueva Trinidad, in the eastern part of Chalatenango, in the mountains. From my house, I could see the Honduran border. I always dreamed of crossing the border to see what lay beyond.

I was born into extreme poverty. My family managed to get by only because my sisters worked in San Salvador as domestic workers and were able to help the family. My sister, the one who later came here, began working in San Salvador at the age of 13. She’s very grateful to the United States, because the treatment she received here as a domestic worker was much, much better than what she received in El Salvador.

For the first seven years of my life there was no civil conflict. There was a lot of poverty, a lot of abuse by the authorities. But it was around 1976 or 1977 when people began to organize. I remember the first thing was the Union de Trabajadores del Campo (Union of Rural Workers) throughout the Chalatenango area.

The church was very instrumental in helping people organize themselves after Medellín (the watershed 1968 meeting of Latin American Bishops in Medellín, Colombia). Medellín awakened a sense of social awareness and a closeness, a conscious awakening.

People began to join different organizations and to read the Bible from that perspective. Seeing faith from that perspective brings liberation, not only salvation in heaven but liberation from what oppresses you here on Earth.

The government’s repression followed immediately after that. Those were years of great suffering. And many people began to look for other places: to leave their towns, to go to Honduras, to form groups of refugee communities.

People began questioning the government because it was clear that it wasn’t a democracy. It was a military government.

I remember very well a massacre on the Sumpul River. We had gone fishing with my mother, because it was May.

My mother has always been a farmer. That was her passion, to farm the land, and I learned farmwork from her, too. She took us to the Sumpul River, but it was swollen; so we went to fish in another river that was closer, called the Gualzinga, a tributary of the Sumpul.

We already knew there was conflict brewing. But we saw a group of people hurrying across the river, carrying bundles. And we said, “What’s going on?”

Up above, about 200 meters further along, was the suspension bridge—a hammock bridge, as we called it, because there were no cars, it was only for people to cross on foot. The guerrillas and the civilians were coming from one side, and the military troops were crossing from the other side. And we heard a big bombardment going on up above. And then we realized what had happened to the village up there: They had all been massacred.

We eventually went to work on some land my grandparents owned on the border, practically in Honduras, and we found that the entire area was a refugee camp for those who had managed to cross the river, those who weren’t killed by the soldiers or drowned in the river.

The conflict continued to the point that the villages were completely emptied out, vacant. People went to Honduras or looked for a safer area around San Salvador or Chalate (the regional capital of Chalatenango). We were still there, and we were very isolated. We had to walk about 24 kilometers to buy provisions.

And that’s how it went until 1982, when we received orders to leave, because the military post that was nearby was withdrawing. The government ordered us to evacuate because they considered that area to be guerilla controlled. They gave us three days to leave, taking nothing with us.

And so we moved to another town, El Paraiso, and there I lived for nine years.

How did you emigrate to the United States?

I was 18 when I made the first trip: I made it to Tijuana. In Tijuana, I was caught by Mexican immigration and was in jail for about two or three days. And from there, I was deported to Guatemala.

After I returned to El Salvador, I made another attempt to cross. This time I went through Guatemala, through the Petén jungle, and we couldn’t cross. We returned to El Salvador, this time on our own.

And the third time, after the conflict, the situation became even more difficult, because of the death of the Jesuits in San Salvador. My sister, who was already in the United States, became very worried. She said, “Let’s look for another coyote (guide).” This time my brother came, too. He was 17; I was 19.

This time we were imprisoned in Chiapas, Mexico. But then they released us after a bribe. And that’s how we managed to cross the border at Tijuana.

I think this marks us. It marks us and makes us who we are. I suffered a lot, but you know, I wouldn’t want to change my life.

You arrived in the United States 35 years ago. What was your experience like?

I arrived in Los Angeles in January 1990. I received a work permit: It was only because of the war that I received a work permit under TPS (the Temporary Protected Status program).

I came with nothing except for many dreams of being able to get ahead economically. There was also the possibility of going to school, since I couldn’t study back in El Salvador.

The first job I found was one offered to me by my sister’s employer—she worked as a housekeeper for a lawyer—as a receptionist in a law office that served 100 percent Hispanics. After eight months, they were going to close the office and move me to their other office, but because of my lack of English, it wasn’t possible. Still, the lawyer helped me get a janitorial job at clinics, cleaning, fixing, painting, doing anything that needed to be done.

After almost two years, that job dried up. Work in Los Angeles became very difficult. I trained to work in dry cleaning, but even then I couldn’t find a job.

Then I decided to move to Maryland, where I had family. My first job was cleaning at a UPS warehouse—I loved that job. After a year, they were going to promote me, but I decided to go into construction instead, because it paid better. I worked in painting and construction for several years. I went to night school to learn English, and I started taking courses to earn my GED.

I couldn’t travel. I couldn’t visit El Salvador. I went seven years without seeing my parents. And in that time, how many died? My grandparents, my sister, and my uncles died, without me being able to go back.

Meanwhile, I spent my weekends helping at my parish in Hyattsville, Maryland. Because of the work I did with young people as a youth minister, the parish sponsored me for a green card. At that time, that was still possible: If you had a paid religious job, you could get a religious visa. None of that exists anymore.

What led you to decide to go into the seminary?

I come from a very religious family. Especially my mother. My father used to ask my mother to gather us together to pray the rosary. She was always the one who led the prayers.

When I was growing up in the canton, faith was lived in community, at home. Not so much by going to church, but rather in the community, through popular piety. Later, when we moved to El Paraiso, there was a parish, priest, nuns, Sunday Masses. There I joined a youth group, for vocational discernment. I was also a catechist. And that’s where my vocation was born, but it wasn’t something that I could pursue in El Salvador because of the armed conflict.

It was when I came here, especially when I joined the parish, that I saw and understood the work of priests. That’s when my vocation was strengthened. Then a window opened here in the diocese so that young people like me, immigrants with no English or formal education, could enter the seminary.

I barely had a GED, but I saw that the Lord truly wanted me to be a priest. When I passed the GED exam, it was a sign for me. When I obtained permanent residency, it was another sign for me, that the Lord was truly calling me to the priesthood.

And that’s when I went to a bilingual seminary in Miami, St. John Vianney. There I was able to begin philosophy classes at the same time I was taking English classes.

How do you see the migrant community coping with the current harsh anti-migrant rhetoric, raids, arrests, and deportations?

With a lot of fear and uncertainty about the future. Two days ago, a parish priest called me to tell me that someone from his parish had been arrested during a raid in Washington. This man was getting married in two days.

Through the intervention of the parish priest, this man was released. He hadn’t committed any crime, and there was no arrest warrant. But he was still afraid to celebrate the wedding even after his release.

People are very afraid to go out, they’re afraid to go to work. But above all, there’s this anxiety of not knowing what’s going to happen. Some people are returning to their countries. I know a family from Colombia who is returning. I know Salvadorans who are also returning, because they don’t see a future here. In many cases, they have to take their children, who are Americans, with them to try to make a new life for themselves in another country. There’s a lot of fear.

Are people taking their children to school, going to church, participating as usual in their parishes?

Well, especially during Holy Week, the attendance was large, at least at the parish where I was, Our Lady Queen of the Americas. People are also trying to strengthen their faith and their community ties.

But there are some people in some areas who are afraid to go to church, especially now that it’s said that churches are no longer considered sanctuaries. And yes, there have also been cases of schools where ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) agents have shown up, recently at a school here in Washington.

People are looking for things to get better, to continue with their normal lives. But it’s like a war, like the war we experienced in El Salvador. You try to live a normal life, but it’s not normal, because you always have this weight hanging over you, this fear that if you go out, they’ll arrest you, or that any day you’ll receive a deportation notice. This stress, this anxiety, is also causing mental illness, constant fear and anxiety, and even depression.

All of this is affecting the community and pushing people to think, “Maybe it’s better if I leave because it’s too stressful. You can’t live a normal life.” Or, “We came to improve our lives, and if this country no longer offers those opportunities, what’s the point of being here?”

Hispanics—immigrants in general—want to invest, to buy a house after being here for many years, to buy a car. But if they’re arrested they could lose everything. That’s the big question people ask: “If I get arrested, who gets the house?” We are working to create plans with them, help them so they have a plan in case they’re arrested and deported.

The U.S. bishops have spoken clearly about the church’s responsibility to defend immigrants. If the church remains faithful to its prophetic roots, could a difficult situation arise for the church in the United States?

Yes, and we are experiencing this ideological divide also within the church itself. I hope we open our minds and hearts and that we are a prophetic people.

The important thing is to remember that all this rejection is born out of fear. Dialogue is important. Native-born Americans are afraid: It is unfounded, it’s a false fear. But then immigrants are also afraid. How can we find a way to listen to one another?

There are some beautiful projects that are yielding results in some dioceses, where you bring in immigrants and people who are anti-immigrant and ask them both, with the help of a trained mediator, what their fears are.

You begin to realize that inside, deep down, within each person, there is first of all fear, yes, but beyond that, behind that, there’s love, too. And there’s hope: to be able to bring out that love, bring out that compassion that fear and lack of information have been obscuring. I think that’s what we have to do.

The problem is that misinformation heightens our fear. Not all immigrants are criminals. Some are, but there is crime in every community. You can remove all the immigrants from the country, and there will still be crime. That’s important to remember.

When people know an immigrant personally, the vast majority of them will say, “You leave my neighbor alone!” or “You leave my employee alone!” Why? Because one-on-one, people have a good relationship. The problem is when we get caught up in the rhetoric.

The important thing is to change the rhetoric. We should not accept that anti-immigrant rhetoric. Why don’t we present a different kind of rhetoric?

What does the gospel tell us about immigrants?

I studied theology in Rome with the Scalabrinis, who specialize in the Theology of Human Mobility. All of sacred scripture is a story of mobility. From the beginning, there were migrants: the people of Israel, the oppressed people in Egypt. But then they are freed and embark on this journey of searching for a land, a place. And that has been the entire history of salvation.

Then we come to the gospel, which begins with Jesus, the Son of God, being a migrant, a refugee in Egypt. And then it says he returns to his country after three years of living there. Joseph is looking for work, surely, with his countrymen who had also fled persecution. And he returns because they thought life would be better in their country. And even then, they can’t settle in their own land, but instead they seek another. They go to Galilee.

Then Jesus welcomes foreigners with great affection. He finds faith in a Canaanite woman, saying no one had as much faith as this woman. The clearest message we can possibly get is when Jesus says, “I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger, and you welcomed me.” If we don’t welcome the stranger, we don’t welcome Jesus. Jesus doesn’t just welcome the stranger; Jesus makes himself a stranger. He is saying, “I am the stranger, the stranger is me.” That love for others is the heart of the gospel.

And then later, with Paul, the good news opens up to all peoples, where Paul says that he is no longer a Jew, he is no longer a Gentile. We are all brothers and sisters.

That is the Catholic vision. That there are no more borders. And yes, countries have the right—all the popes have said this—to protect their borders. They don’t have to be “open borders,” but human dignity must be protected. We find in the gospel so much material in defense of human dignity, seeing the person as the image of God.

What impact do you think the election of Pope Leo will have on immigration in the United States?

Why has the church been abandoning solidarity with workers? That is essential here in the United States. The immigrants who came from Europe at the end of the 19th century founded these brotherhoods and fraternities of laborers.

The church has remained very close to labor unions, which is different from other countries in Latin America and Europe. In the United States, the church has fought shoulder to shoulder with labor unions, which have actually remained very Catholic.

Another beautiful legacy of the American church is the legacy of mission. We can’t forget the American martyrs in Latin America, the religious sisters who died in El Salvador, or the other American martyrs, such as Sister Dorothy Stang, murdered in Brazil for defending the Amazon, or the priest who was killed by Lake Atitlán in Guatemala, Father Stanley Rother.

Robert Prevost is part of this American missionary tradition, of this solidarity of the American church with Latin America. It’s beautiful: His election is like a maturing of that missionary spirit of the American church.

My concern is that in recent years the American church has become more withdrawn, more inward-looking. That’s why Pope Francis told us that the church must be an outgoing church. That outgoing church of the 1970s and 1980s here in the United States is not this church we see today, which seems to be in hiding.

And that’s why Pope Francis said, “I prefer a church which is bruised, hurting and dirtied from being out on the streets, rather than a church which is unhealthy from being confined.” Leo XIV comes from that bruised, hurting church, but he sees the church as outgoing, a church unafraid of mission and of accompanying the poor, and preaching the gospel there, and suffering repression together with the people.

I hope there’s a resurgence of that missionary church here in the United States and throughout the world.

This article also appears in the August 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 8, pages 16-20). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

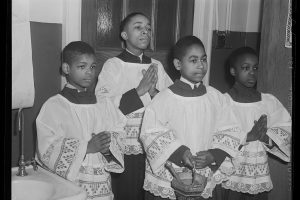

Image: Courtesy of Auxiliary Bishop Evelio Menjivar-Ayala

Add comment