Pints with Aquinas is a 21st-century podcast named for a 13th-century theologian—and, with millions of downloads, it’s one of the most popular Catholic audio or video programs today. Every week, host Matt Fradd, an Australian apologist and anti-pornography activist, conducts long-form interviews about typical “trad Catholic” topics such as abortion, homeschooling, and sexual sin.

The show is not really about Thomas Aquinas, although Fradd mentions him frequently and has written and self-published a book titled You Can Understand Aquinas. He admits he’s no expert and instead describes himself as a “studious amateur” of the medieval scholastic.

Fradd launched the podcast in 2016 as an extra-credit project in graduate school. “I liked the idea of bringing the angelic doctor down out of the ivory tower of academia to mix with the riffraff like me,” he said in an EWTN interview. Why Aquinas? “Because he addressed almost every topic under the sun.”

Fradd is not the only conservative Catholic to adopt Aquinas as a personal hero. Many other conservative Catholics are attracted to Aquinas for the same reason, believing that he is a “once and done” kind of theologian, one with all the answers to theological questions.

In fact, the Dominican friar and priest has become something of an icon to some Catholics, held up as the definitive expert on Catholic doctrine and moral teaching, and his Summa Theologica is used to prooftext everything from whether dogs go to heaven or wet dreams are sinful (he says no, in both cases).

Aquinas’ recent favor among traditionalist Catholics may be thanks to his association with natural law, his reputation as the “universal doctor” of the church, or the mistaken view that he coined the phrase “intrinsic evil.”

The kind of Aquinas quotes shared on social media hint at why he’s attractive in certain Catholic circles, even if the quotes’ provenance is questionable. “The greatest benefit that can be done to a man is to lead him from error to truth,” is a popular meme. Another one: “To one who has faith, no explanation is necessary. To one without faith, no explanation is possible.”

How did this doctor of the church become the hero of contemporary conservative U.S. Catholics? In some circles, especially online, Aquinas has become equated with tradition, black-and-white thinking, and being the “right” kind of Catholic.

Yet actual experts who study Aquinas say such branding is not only inaccurate but also ironic, since Aquinas’ theological method is antithetical to the culture war thinking of today. Aquinas actually encouraged—and modeled—how to engage with other, even non-Christian, ideas of his day.

Rather than encourage a similar methodology, some 21st-century Catholics prefer to see Aquinas as having settled every theological and moral debate in the 1200s.

“Thomas has become an icon in a certain form of Catholicism, a magisterial Catholicism that’s bound up with authority, tradition, and history,” says Craig Ford, an assistant professor of theology and religious studies at St. Norbert College in De Pere, Wisconsin who has studied and written about Aquinas.

That simplistic view of Aquinas is a caricature, Ford notes. Franciscan Father Daniel Horan, a professor of philosophy, theology, and religious studies at St. Mary’s College in Notre Dame, Indiana, agrees. About the way Aquinas is being used today, Horan says, “I can’t help but think that Thomas is rolling over in his grave.”

Aquinas’ attraction

When the Alabama Supreme Court ruled in February that frozen embryos used for in vitro fertilization (IVF) are to be legally considered children, Chief Justice Tom Parker used a number of religious arguments in his opinion. Among his sources: the Bible, a 16th-century Dutch Reformed theologian, and Thomas Aquinas.

“Following Augustine, Aquinas distinguished human life from other things God made, including nonhuman life, on the ground that man was made in God’s image,” wrote Parker, who went on to quote the Summa. “Aquinas taught that ‘it is in no way lawful to slay the innocent’ because ‘we ought to love the nature which God has made, and which is destroyed by slaying him.’ ”

Setting aside the legal question of whether religious arguments belong in a court opinion, the ruling illustrates how Aquinas is often co-opted into contemporary debates. The example is unique, in part, because Parker is Protestant.

The use of Aquinas in a debate about IVF is especially ironic, given that he didn’t believe that human life came into existence until well into pregnancy (and that female embryos were created out of male ones, perhaps from the influence of a southerly, moist wind). “To cite Thomas Aquinas in support of the value of the early embryo is, at the very least, tone-deaf,” theologian Charles Camosy told the Washington Post.

So what is Aquinas’ attraction to Parker and others?

It may be that Aquinas’ medieval worldview and the sense of orderliness that comes from his systematic writings are comforting in a time of massive societal change, says Angela Denker, author of Red State Christians (Broadleaf Books), who has researched and written about conservative Christianity.

“It’s a return to things that feel like touchstones, when the church was the heart of the world and at the seat of governmental power,” Denker says. “With the abuse crisis and loss of trust in institutions, including the church, this sense that everything could be orderly and explainable feels attractive for people who are looking to make sense of the world.”

These views often come from a facile reading of Aquinas, Denker says, adding that such surface knowledge becomes acceptable in a society that has de-prioritized expertise. “What’s attractive is the kind of culture that people imagine Aquinas would support,” she says. “When we’re talking about white, conservative Christianity, what’s increasingly holding it together is culture, not theology.”

In the Catholic sphere, those championing Aquinas often have a strong media presence. Bishop Robert Barron, founder of Word on Fire media ministries, considers himself a Thomist, and one of his first books was about Aquinas as a “spiritual master.” Another high-profile Catholic in the media, Father Mike Schmitz of The Bible in a Year podcast fame, calls Aquinas the “theological heavyweight champion of the world” and cites him frequently. The St. Paul Center, run by apologist and best-selling author Scott Hahn in Steubenville, Ohio, recently launched a project to translate and publish all of Aquinas’ writings. Aquinas’ name is also frequently dropped in the pages of First Things, a conservative Catholic journal that has taken an extreme right-wing turn in recent years.

While many schools and organizations are named for Aquinas, perhaps best known is the Angelicum, or the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas, run by the Dominicans in Rome, whose most famous alumnus is St. Pope John Paul II.

While not every eponymous organization is conservative, many are. The Thomistic Institute, part of the Dominican House of Studies in Washington, D.C., has as its goal to “promote Catholic truth in our contemporary world.” At least one homeschooling program is named after Aquinas, and many feature his work in their curricula.

While most undergraduate students, even at Catholic schools, likely only get a taste of Aquinas in an introductory theology course, Benedictine College in Atchinson, Kansas—called the “flagship college of the new evangelization”—touts that its philosophy department is centered on Aquinas.

The “common doctor”

Many contemporary fans of Aquinas point to Pope Leo XIII as having done the most to confirm Aquinas as the theologian above all others. Leo’s 1879 encyclical Aeterni Patris (On the Restoration of Christian Philosophy) held up the teachings of Aquinas as definitive, decreed that all Catholic seminaries and universities must teach his doctrines, and named him the “common doctor” of the church.

The encyclical came during a period of post-Reformation neoscholasticism, which doubled down on Catholic sources in response to Martin Luther’s argument for a return to biblical sources. Protestant critics had famously mocked Aquinas and other medieval scholastics for arguments over, for example, how many angels can dance on the head of a pin.

“People think Thomas has been the guy forever, but it’s simply not true—until a pope 145 years ago decided it was going to be,” says Horan, who notes that the encyclical also names St. Bonaventure as a preeminent doctor of the church along with Aquinas.

Contemporary scholars say Aeterni Patris has been widely misunderstood, especially by “online keyboard warriors,” as Kate Ward, an associate professor of theological ethics at Marquette University in Milwaukee, describes them.

“Even in that encyclical, what Leo XIII is not saying is that we can only believe what Aquinas believed in the 13th century,” Ward says. “He certainly isn’t saying that all of Aquinas’ teachings are infallible teachings of the church hierarchy. That isn’t the case for any theologian. . . . He says we should teach what could flow from Aquinas’ thought. He’s saying we could update.”

Favoritism toward Aquinas got another boost in the late 20th century, thanks to a theological movement called “radical orthodoxy.” This school of thought believed that a retrieval of historical Christian theologians, notably Augustine and Aquinas, would cure the problems of modernity. The movement was critical of the use of the social sciences and of medieval Franciscan philosopher John Duns Scotus. Although initially founded by Anglicans, radical orthodoxy was popularized within Catholicism by Bishop Robert Barron and the late Chicago Cardinal Francis George.

Radical orthodoxy is informed by theologians such as Henri de Lubac, Hans Urs von Balthasar, and Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI). These men were also founders of Communio, a journal started in the aftermath of the Second Vatican Council in response to the “new theology” they saw as too accommodating to modernism.

Mike Lewis, founder of the website Where Peter Is, believes that some of those past theological conflicts continue today. “People who like this black-and-white thinking have been able to persist in it since Vatican II,” he says. “It has really flourished in the Francis papacy, in the opposition to Pope Francis.”

Horan, who has been critical of the radical orthodoxy movement, also sees it as having influenced conservative Catholics on social media, especially those who dislike Pope Francis. He believes they misunderstand Aquinas, if they even read him. “They’re presenting a kind of neo-neo-Thomism,” he says. “It’s rarely actual engagement with Thomas Aquinas.”

Ward acknowledges that Aquinas may speak to people who are less comfortable with ambiguity and prefer clear answers. “[These people] remind us that authority, and the unitive function of authority, is an important part of our faith,” she says.

She distinguishes that from online trolling, however, and reminds those who want clear answers that Aquinas actually taught that the more we descend from principles, the more likely we are to get it wrong. “He understood human experience enough to know that people want that clarity, but that life doesn’t always fit our principles,” she says.

Ford, the professor from St. Norbert College, also recognizes that Aquinas fans’ use of natural law as a “trump card” can seem like a seductive way to cut through messy discourse. But there are no easy answers, he says. “Natural law talks about the tendencies that make us the creatures that we are,” he says. “But how to go about pursuing what we’re drawn toward? That’s the whole matter of the moral life and the virtues.”

Ironic icon

Given that “Thomist” has become something of an ideological badge, a synonym for a more conservative doctrinal viewpoint, do progressive theologians and Catholics shy away from studying him?

Not in academic circles, where no one “side” owns Aquinas, and scholars from various perspectives engage with his work. In fact, the kind of scholars trad Catholics criticize—those who may disagree with official church teaching on some matters—are using the very method that Aquinas models. Examples include feminist theologians such as Elizabeth Johnson, not to mention Pope Francis, who described his apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia (On Love in the Family) as “Thomist, from beginning to end.”

Jean Porter, a professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame, has written five books on Aquinas and natural law. She also has used Aquinas to argue for the moral acceptance of same-sex marriage.

“I love St. Thomas and have happily spent my whole adult life studying him. I’m second-to-none in my admiration of St. Thomas,” Porter says. “But I think it’s important to see him as part of a tradition of serious debate and inquiry.”

Porter and others say it is especially unfair to paint Aquinas, or any of the scholastics, as “once and done,” since their debate and discussion on disputed questions was a particularly open-minded way of doing intellectual inquiry. “Nobody is ever once and done,” Porter says. “It doesn’t make sense, on Thomas’ own terms, to freeze him in that way.”

Ward agrees: “His work is not intended to be closed or to be the final answer to anything,” she says. “He himself, in his teaching, was updating the teaching that he received.”

In fact, Aquinas’ dialogue with Greek and Islamic philosophers was seen as extremely controversial in his day. After Aquinas’ death, the archbishop of Paris actually condemned his writings and the master general of the Dominican order forbid that he be studied. “As Aquinas saw it, he was doing his best to take the received tradition and express it more fully and truthfully in light of new knowledge,” Ward says.

That’s what other scholars are doing with Aquinas today. For example, Ford’s work seeks to reclaim natural law within the conversation on transgender identity and sexual orientation, arguing that gender curation is a moral project.

Aquinas’ synthesis of Aristotle, who was not Christian, and Augustine, who was, demonstrates a method that continues to be relevant today, Ford says. “Along the way, Aquinas got things wrong. He was limited by his time period,” he says. “We have to remember that he’s in an intellectual conversation, and he never exempted himself from that conversation.”

In fact, the centerpiece of Aquinas’ moral theory is that Christians must grapple with moral questions, Ford says. “God helps us with this, but we can’t take a back seat and cede it simply to, ‘This is the answer.’ ”

To be “Thomistic,” Ward says, is to think with reason and science to try to figure out what God wants for us. And all Catholics and Christians should be doing that. She and other scholars encourage all Catholics—no matter what their ideological slant—to read Aquinas and engage with his ideas and method. “It’s all part of our heritage and our inheritance,” Ward says. “We shouldn’t let anyone tell us what this person means—that Aquinas is a just a rubber stamp to put on everything. He’s not.”

Horan believes that if Aquinas were alive today, he most certainly would not be in favor of Catholics simply repeating his 800-year-old arguments based on 800-year-old science, worldviews, and philosophy. “He’d be horrified by that,” Horan says.

This article also appears in the July 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 7, pages 10-25). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

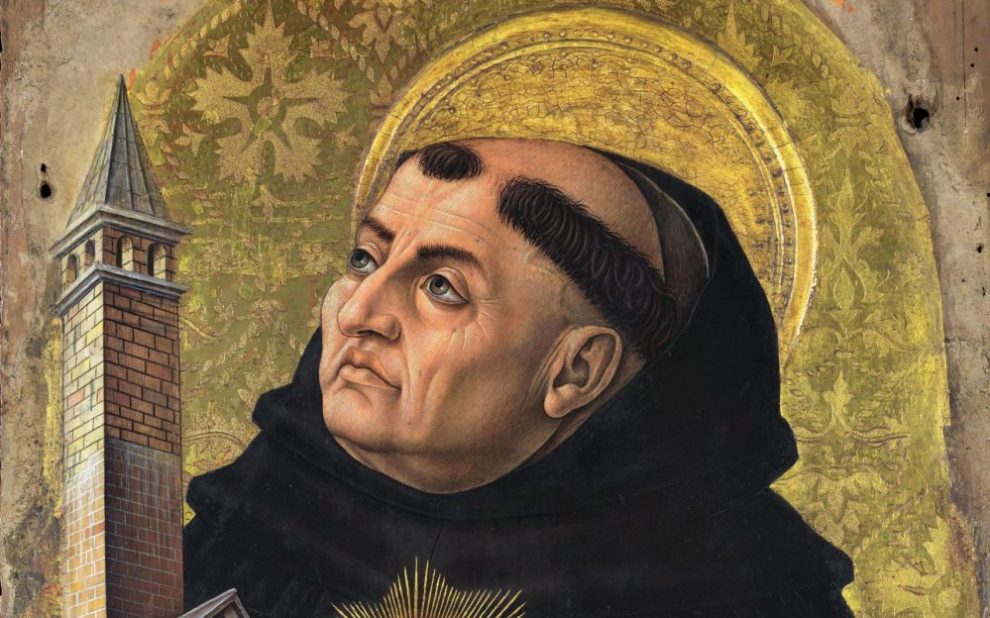

Image: St. Thomas Aquinas, Carlo Crivelli, circa 1435–1495, The National Gallery

Add comment