Lent is a powerful and humbling time in which we are implored to “repent and believe in the gospel.” The liturgical progression through Lent should challenge our assumptions and confidence about what we think we know about God, Jesus, and ourselves. Who is Jesus of Nazareth? He has the words of salvation, but do we hear them? He is the way, but are we prepared to follow?

Looking at the psalms in the Sunday lectionary that weave through our Lenten journey, we begin in confidence: “Your ways, O Lord, are love and truth to those who keep your covenant” (Ps. 25) and “I will walk before the Lord, in the land of the living” (Ps. 116). Yet, as we move toward the third week, the psalms get more tentative and pleading: “If today, you hear his voice, harden not your hearts” (Ps. 95). Once again, we are asked: Are we listening? Are we awake? Psalm 23 is paired with a gospel in which Jesus’ authority to heal is challenged. And ultimately, in week 5, a personal plea: “Create a clean heart in me, O God” (Ps. 51).

The narrative of the psalms is a progression toward embracing a humble faith that is truly open to God and neighbor. In Fratelli Tutti (On Fraternity and Social Friendship), Pope Francis cautions that “belief in God and the worship of God are not enough to ensure that we are actually living in a way pleasing to God.” A humble faith, or as the pope frames it, an “authentic openness to God” that we all seek, is a “way of practicing the faith that helps open our hearts to our brothers and sisters.” As we journey through Lent, where does the journey to Calvary begin? While liturgically it begins on Ash Wednesday, we should begin in Bethlehem.

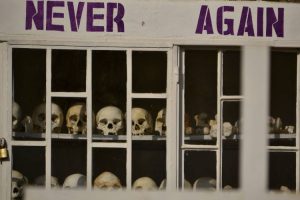

At Christmas, more than a thousand refugees and asylum seekers were brought to a makeshift camp at Floyd Bennet Field near where I live in New York City. All levels of government have failed to respond adequately to the influx of migrants here. However, more disturbing than the lack of response has been the dehumanizing rhetoric and hostility toward both new migrants and those who seek to help. One community member collecting coats and basic supplies for migrant families faced online harassment after being doxed by an anti-migrant social media group.

Immigration is central to identity narratives of the United States. This reality is complicated. On the one hand, the United States is a nation of immigrants; at the same time, it is a nation that has resisted and demonized almost every successive wave of migration. A welcomed wave of immigrants coming the “right way” has never existed. For Catholics, it is important that we be attentive to this complicated history lest we risk hardened hearts when we meet Christ in our migrant brothers and sisters.

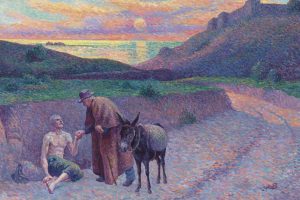

Sin, according to Jesuit Father James Keenan, arises most often not from pride or action but in the “failure to bother to love.” On a recent visit to Chicago, I walked by no less than six families positioned along the street begging for assistance, begging to be seen. While I was able to give some money to the first family, I was not able to help them all. It was painful to walk by while acknowledging their presence, knowing they had no other options. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle worried that if cities became too large, we would become callous to the troubles of our neighbors. While he was not envisioning Christian love, I think it is like Keenan’s vision of sin: Community and human dignity break down when there is a failure to bother to love.

At the same time, migrant families themselves have much to teach us about humble and constant faith this Lent. In 2022, I visited migrant mothers with young children in Juarez, Mexico, and El Paso, Texas, as part of the Vatican’s Doing Theology from the Existential Peripheries program, accompanied by Hope Border Institute. Fleeing with nothing except what they could carry, the mothers to whom I spoke were adamant that God was with them. In extreme vulnerability, their faith and hope were astounding. In the face of fear, they chose faith—in God, in themselves, in the possibility of their children’s flourishing.

In the families at Floyd Bennett Field, begging on the streets of Chicago, or arriving in El Paso, Texas, I see those healed by Jesus who, despite their marginalization, embrace hope. “They compel us,” says Pope Francis in Fratelli Tutti, “to recognize Christ himself in each of our abandoned or excluded brothers and sisters.” And in doing so, to walk the Lenten journey with Christ.

This article also appears in the March 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 3, pages 40-41). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Kevin Buckert

Add comment