As an adolescent, I never thought I would end up working in theology and ministry. For me, Catholicism was to be tolerated for the sake of family. No more, no less. As a suburban white teenager in the 1990s, I went through the motions of receiving the sacrament of confirmation. I mainly did it at the insistence of my dad. It was his way of passing on the inheritance of faith and culture he had received from his family. After ongoing protest from me, he finally sealed the deal when he said, “Kevin, you don’t have to believe every single thing that the church believes. Just the basics. And if you do, please go through with this.”

After all, my Irish ancestors had defended and lived their Catholic faith in Akron, Ohio despite the opposition of many white Anglo-Saxon Protestants associated with the Ku Klux Klan who practiced discriminatory violence against them. My father had been called a “Mackerel Snapper” (look it up) in his childhood and faced interpersonal anti-Catholic bias as a Brother of the Holy Cross in the 1960s in Texas and throughout the South. Moreover, my older brother had already been confirmed. Now it was my turn.

So, I received the sacrament to fulfill my obligations to my parents, family, and ancestors. And afterward, in the decade that ensued, I rarely gave it another thought, as I seldom attended Mass unless cajoled by my parents. I was angry with God and saw the Catholic Church as an outdated, regressive, somewhat harmful institution. Other than honoring my family and forebears, I could not understand what the point was in being a practicing Catholic. I knew I would always be “Catholic” in sensibility, spirituality, and cultural roots, because Protestantism in all of its forms made even less sense. Many of my Protestant and evangelical peers had constantly tried to convert me to “Christianity,” asking me to accept Jesus in my heart and join their churches so I wouldn’t go to hell when the rapture came. I wasn’t buying that either. So by the time I was confirmed I had little use for any of this nonsense associated with institutional Christianity of any denomination.

This was in the 1990s and lasted into my young adulthood in the early 2000s. But I think some similar challenges associated with the intergenerational passing on of the Catholic faith remain. Passing on faith and tradition from one generation to the next has never been an easy task. One important aspect, in particular, seems to be missing in many Catholic communities today just as it was in mine back in the day: mentorship in the faith.

Mentorship is difficult to define, to discern, and to practice. It is a strange relationship because it often develops outside the family structure. In psychological development, a young person is severing childhood ties with parents while (hopefully) preparing to eventually establish a more adult relationship with them, so a mentor cannot be a parent. Sometimes a mentor is an older family member by blood. More often, a mentor shares a similar cultural background but is not in the immediate, intimate circle of family and friends. He or she has an inner-authority of their own that a young person intuits and by which they are intrigued. Sometimes a mentor is a teacher, a coach, a professor, or other times a priest, religious sister, or religious brother. They are a more seasoned soul whose accompaniment can guide a young person’s questioning while positively imprinting the presence of a wise elder upon their mind, body, and spirit.

Scripture offers a solid foundation for understanding mentorship. In the gospels, there is a similar relationship called discipleship. Jesus of Nazareth calls many disciples, some of whom become apostles, and a disciple is a student tasked with learning from the teacher through listening, sharing life, and eventually imitation of the teacher. The disciple learns through close observation and continuous practice—similar to an apprenticeship—and at various stages will be asked to demonstrate what they have learned. After all, the earliest name for the followers of Jesus was not “Christianity” or “the church.” It was “the Way.” It referred to those who dedicated their entire self to living out the way of life taught by Jesus the Jewish prophet, Son of God, and mentor par excellence in living in harmony with God’s Spirit.

Similarly, a mentor relationship is one of being accompanied by a trusted elder or compassionate authority figure as you learn to be a part of a faith tradition. You pose questions and express rage, despair, and laughter as you figure out your distinct relationship with your faith community and with God. You freely receive wisdom from a mentor who chooses to freely offer it. There are few expectations or goals other than stewarding the relationship for a season. A mentor is a “wise guide” who helps you navigate difficult and sometimes painful terrain in your journey into a more mature faith and way of life.

It is important to point out that both provide room for growth and challenge. At an early turning point in the synoptic gospels, Jesus sends out the disciples to go practice what he taught them (Mark 6, Luke 9, Matt. 10). In Matthew’s gospel, Jesus tells them, “As you go, proclaim this message: ‘The kingdom of heaven has come near.’ Heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse those who have leprosy, drive out demons. Freely you have received; freely give” (Matt. 10: 7–8).

Here, Jesus is a teacher who has great faith in his students—perhaps more faith than they have in themselves. They go out, do the work, and later return and report how it went. The core of this is the relationship of mutual respect and trust with Rabbi Jesus. His students were called “disciples” and they called him “master,” “rabbi,” and “teacher.” One of the closest words we have in English that holds some similar meanings is “mentor.”

This gift of being mentored in the faith is similar to the practice of discipleship. It is learning how to exist consciously in God’s presence on a daily basis, which also means learning to become more human. It is not about right belief as much as it is about healthy life orientation in God’s presence. To paraphrase theologian Karl Rahner, the more deeply we encounter the mystery of God, the more authentically we embody the mystery of being human. And the more authentically we embody the mystery of being human, the more deeply we encounter the mystery of God.

This is a paradox of transformation into a more authentic humanness in which a mentor assists. A mentor is a midwife, a wise guide, an elder in faith, and one who assists with following the Way of Jesus that is appropriate to one’s own context, gifts, and commitments. They assist one in articulating an authentic response to the religious question in life: “To whom do I belong?” And a mentor guides one in learning that to follow Jesus’ Way and to become ecclesial means to learn to exist for all others who are not yet as aware of the profound healing, love, dignity, and shalom that embraces one who learns to attune to God’s presence in daily life.

This is not identical with formal spiritual direction. A person who enters into spiritual direction goes with an intention to specifically focus on their spiritual development with a seasoned director. Although it shares some similarities to spiritual direction, mentorship is a more organic connection that arises through first developing a relationship. Not all mentorships consist of being directed as much as observing, learning from, and even mirroring the presence of a mentor to others.

Later in my young adulthood, I was fortunate enough to encounter a faith community that embodied this “Way” of Jesus. It was not through a Catholic parish, however, but through a charismatic evangelical church called the Seattle Vineyard. I agreed to go to church there with my then-girlfriend (now wife of 16 years) as a way of preserving our relationship. I still was angry with God and all things “Christian” but for her I would give this a try. I quickly marveled that this church, in all of its imperfections, really tried to live out Jesus’ Way by focusing on ministries of healing, empowerment, prayer, and justice. I had never experienced anything like this before. It was a space where a person experiencing homelessness and a young professional would worship together.

In one sermon, the pastor at the time said they’d know if they were being true to God if they could answer “yes” to three questions: Do the sick find healing? Do the oppressed find freedom? Are people able to find peace with God? To me, those three questions pointed to a way worth following. I joined a weekly community group of young adults that focused on prayer, scripture, and building a community of mutual support, care, and compassion for that season of our lives. We met in a home, got to know one another, ate together, laughed together, questioned together, and supported one another in young adulthood’s challenges and victories.

If I had not committed a small part of my life to being part of that community while I tended others’ wounds as a social worker and reencountered many of my own that had been obscured by bad habits from surviving trauma, I would not be a theologian and minister today. The community accepted me for who I was, did not pretend my wounds didn’t exist, and accompanied and guided me as I relaunched my interest in theology and ministry in the Catholic tradition. It is because of this experience of reciprocal love, acceptance, and accompaniment that I eventually moved across the country with my wife for graduate school in Chicago.

And, since God’s Spirit moves unexpectedly, I encountered my own mentor in graduate school and began to reengage with Catholicism in a serious way. I had the privilege of years of learning, being empowered, and being gently challenged to live well in the presence of the living God by a mentor who showed that the Way of Jesus was alive and well in some forms of Catholicism. For this mentorship, I will be forever grateful.

These Spirit-infused relationships, both within and between generations, are what bind people together. They are how faith is enculturated, interpreted, and passed on to the next generations. They are the primary ways that God reminds us of God’s love and invites us into a community of faith in the Way of Jesus.

Mentorship and accompaniment look different for different seasons in life. For me, both became sacraments to trust that God is at work in the Catholic tradition that was being passed on to me. And that I, or anyone, could authentically be a part of that tradition and learn to do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with our God (Mic. 6:8). Not perfectly, of course. But with authenticity and integrity nonetheless.

This article also appears in the May 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 5, pages 17-19). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

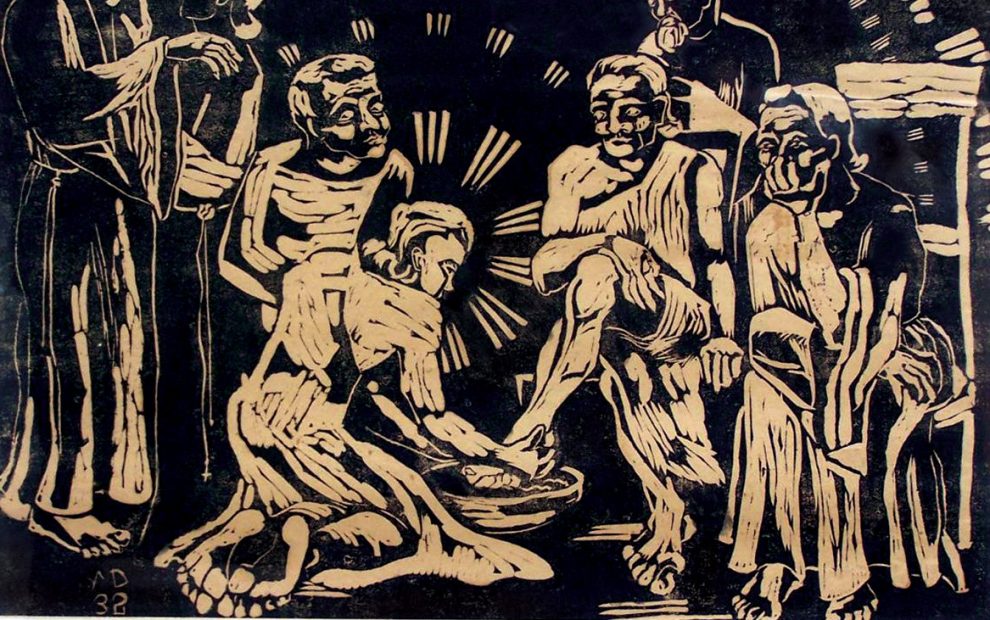

Image: Footwashing, Margret Hofheinz-Döring, 1932. Via Wikimedia Commons

Add comment