White Christians’ approach to solving the ecological crisis is flawed, says Jawanza Eric Clark, a professor of global Christianity at Manhattan College. While there have been several prominent theologians who have boldly proclaimed that it is time for a new way of thinking about the relationships between God, humanity, and creation, the vast majority of these thinkers miss something vital: They neither consider race nor how oppression of the natural world ties into other forms of oppression, mainly against Black and Indigenous people throughout history.

In his new book, Reclaiming Stolen Earth (Orbis Books), Clark offers a new framework for ecotheology, one that uses the land as a symbol that can bridge race, class, and gender. This theology is one that takes into account the wisdom of Indigenous cultures around the world (particularly, in Clark’s case, of African Indigenous cultures) and has the possibility to combat white supremacy and bring about true liberation.

For liberation, Clark says, is not about looking forward to some distant time and place where Christ will return. It means ending systems of oppression and destruction here, now, today. It happens in the present day, on the land on which we stand. “The land is a living reality; it’s not something we own and can possess,” he says. “Liberation has to include land recovery and a change in how we see the land.”

What is ecotheology?

Ecotheology is an attempt to allow Christian theology to confront the problem of the ecological crisis in which we find ourselves and to present a theological response. It is to do theology in a way that tries to address this obviously urgent problem. Ecotheology requires us to reconceptualize some of the traditional ways we’ve done theology, whether that be how we conceive God, how we think about sin, or how we think about space and place.

My argument is that there have been too many voices left out of this conversation when it comes to Western Christian ecotheology. Part of what I try to do in Reclaiming Stolen Earth is to suggest that we need to invite these voices that have often been suppressed and oppressed, in large proportion because of the way in which the Christian tradition has operated, to guide the discussion about God and creation. These subjugated perspectives need to be brought to bear on what ecotheology looks like.

What perspectives are lacking in Western ecotheology?

Elizabeth Johnson talks about a “conversion to the Earth,” which she describes as a shift away from a human-centered view of theology to a spirituality that sees God in all of creation. To me, this is problematic for a number of reasons. First, it ignores the church’s legacy of forced conversion. Particularly among African Americans, there’s a whole history of being made to convert in order to be accepted as a human being. So that whole language is troubling.

But in addition, it implies that this Earth-centered theology is something new. But there are religious traditions around the world that were already eco-centric. We can’t move forward in developing an ecotheology without acknowledging what we’ve skipped over and the legacy of those whose voices have been denied access. These aren’t new ideas. They are just suppressed ideas, because they weren’t coming from white Western Christians.

Likewise, in her book Body of God, theologian Sallie McFague discusses the need to focus on space and place without the slightest acknowledgment that Indigenous religious cultures around the world were already doing this and were demeaned as primitive, uncivilized, and heathen for doing so. White Western Christians are currently calling for a shift because of the urgency of the ecological crisis without the slightest bit of accountability for how white hubris might be the reason for the ecological crisis in the first place.

Christianity needs to reconcile with the past and what it has wrought upon both Black and Indigenous communities and the Earth. There is currently this sort of “come to Jesus” moment, if you will, where we now want to change the way we do theology in response to this ecological crisis. Ecotheologians, specifically, are arguing that Christian theology needs to transform itself. However, they often fail to acknowledge the legacy of what has happened and what the church has done. Too many ecotheologians want to use the same sort of Christian categories that have contributed to the problem in the first place.

So, I suggest a paradigm shift, incorporating voices that perpetuate or promote Indigenous spirituality around the world. Since I’m a person of African descent, I focus on traditional African spirituality. But I could have also focused on Native American spirituality, etc.

In “Whose Earth Is It Anyway?” James Cone asks why the racial justice movement is unrelated to the ecological justice movement. In large part, both these movements are connected, and the logic of white supremacy is evident in both movements. And yet, we often talk about these as two separate issues that are unrelated.

In your book, you contrast Western theology, which you describe as temporal, with Indigenous theologies, which you describe as spatial. Can you expand on this differentiation?

I argue that traditional Western Christian theology is rooted in a temporal orientation, which is to say that they prioritize time over space. The consequence of this is that they’re always either looking forward or facing backward. The present moment is dismissed as being of the least amount of importance.

If you think about liberal notions of progress, or even scientific theories such as Darwin’s theory of evolution, they’re focused on the idea that the future will be greater than the past was. We’re always in a sort of motion, getting better over time. Then, in a traditional Christian sense, we’re fixated backward on the Garden of Eden, or on the first century when Jesus walked the Earth. There’s a sense in which those represent some more pristine moment when God was more active. That they are more important historical moments than what is going on presently. I talk to my students about Easter as a ritual. We replay the first century events—that week culminating in Jesus’ death—over and over again as a way of saying, “This is when God was at work.”

What does that mean for the present moment in which we live now or the spaces we occupy in the here and now? We never focus on that. Now contrast that with Indigenous religions—Native Americans and Africans—who focus more on the spatial. I quote Vine Deloria, a Native American theologian, who compares the two focuses and who says that Christian theology, because of this temporal focus, creates categories that become overly abstract and disconnected from the practical. In part because we’re waiting for the return of Jesus or some eschatological future or back toward the past. On the other hand, Deloria says, spatial thinking is less abstract, more practical, and more focused on being in right relationship with the spaces around us. This includes both other people and the natural world.

In my book, I argue that liberation theology should be especially concerned with making this shift and that Black theology, even though it presents itself as a theology of liberation, is sort of caught in this traditional way of being temporally oriented.

Can you give an example of how Black Christian theology might become a little more spatially focused?

There needs to be a critique of the effectiveness of certain Christian theological symbols and how well they’ve served oppressed people. If Christianity can be interpreted in a way that can lead to liberation, as Black liberation theology suggests, then how effective have these Christian symbols been?

In my book, I focus both on the Bible and the cross as Christian symbols. I highlight James Cone’s way of interpreting both of these and suggest that these symbols have not served Black Christians well, in part because we read them through what I call “white epistemological hubris.” This means that, for example, we try to interpret the Bible in an objectively true way as the word of God. And that becomes problematic when it has us identifying with the “male heroes” of scripture rather than seeing ourselves and our own experience in the biblical narrative. I argue that we’ve reified the Bible and turned it into an idol. We’ve done likewise with the cross. The glorification of suffering is not helping Black Christians. It does not help us address issues surrounding how to overcome or be liberated from racial oppression sufficiently.

In my book, I suggest a new theological symbol, taken from Indigenous African perspectives: the ancestors. I believe this symbol is more attentive to the spatial, because the ancestors didn’t just live in the past. They are present with us, and they exist in the natural world. From a traditional African point of view, the goal of human existence is to become an ancestor, so they also represent a model to emulate. So we need to be in right relationship with them at all times, and this means honoring the natural world, not objectifying it.

Finally, I talk about reclaiming spaces, reclaiming the Earth itself. Both in a literal sense, but also in terms of how we see the land as a living reality instead of breaking it up into pieces that we can possess and control.

What is the place of the Bible then in terms of understanding our faith?

I think it’s one source of wisdom among others. I’m not for complete dismissal of the Bible, but I don’t think it should be our primary source of religious revelation. I argue for what Randall Bailey calls a “freedom of interpretation.” In other words, each person reads the biblical text in a way that conforms to our collective experience. So, in a sense, I elevate collective experience as a source of revelation over the words on the page themselves. In other words, our experience should inform how we read the text.

In the book I talk extensively about the Exodus narrative and the conquering of the Promised Land: what that meant for the Canaanites and how the people who were already on the land got dispossessed. There’s a long history in the Black American Christian experience of reading Exodus and identifying with Moses and the Jews who were slaves in Egypt and freed by God. But really our experience is more like that of the Canaanites than that of the Jews. Can we acknowledge that? What would it mean for the weight and significance this story had in the past and continues to have?

I talk about the “myth of objectivity”: Just because something is in the Bible doesn’t mean I accept it as objectively true or as conveying some divine truth. If we remove that from our interpretation, then perhaps we can decide based on our collective experience which stories have meaning and value and which narratives have been turned into idols. Even when it comes to dealing with the Jesus story—crucifixion and redemptive suffering—this has a strong legacy in the Black Christian community, but some theologians are beginning to challenge this interpretation.

These are some of the cornerstone concepts I suggest have been overvalued in how we think about Christian theology. I’m not dismissing the Bible so much as suggesting that we take a more critical lens. Other theologians have made similar arguments. I particularly reference Delores Williams, who talks about identifying with Hagar and suggests that a Black woman’s experience is more like those of Hagar and Ismael than those of Abraham, Sarah, and Isaac.

Could you talk a little more about the ancestors as a theological symbol?

In my first book, I develop a doctrine of the ancestors in Indigenous Black theology and accuse Black Christian theology of subscribing to an exclusive Christology where Jesus is obviously preeminent and the singular revelation. Believing that is what makes Black theology conform to whiteness: It’s not a concept we would have in our tradition had white European Christians not introduced it to us. It’s entirely foreign to an Indigenous African way of thinking.

By incorporating this notion of the ancestor, it doesn’t get rid of Jesus. But Jesus becomes one among a pantheon of important individuals, men and women who have lived an exemplary life and whose example we should follow. Jesus becomes an important ancestor because of the way he lived his life and the model he gives us about how to love. But the category can also include other people—people such as Nat Turner, Harriet Tubman, or individuals from our own particular family line. It becomes a category that allows us to acknowledge that there’s no singular experience or representation of truth that we all have to subscribe to. There are multiple models of excellence.

Is there still a place for Trinitarian theology in this theological framework?

Well, in my theology there’s no place for the Trinity in the traditional sense of Father, Son, Holy Spirit. However, I think I agree with ecofeminist Ivone Gebara, who talks about the Trinity as an important idea in terms of symbolically representing how the one relates to the plural. She talks about unity in plurality.

This notion of the Trinity overcomes binaries and mutually exclusive categories. Three is a metaphor for multiple—it could be 100, 1,000, or 10,000. The way she describes the Trinity actually connects to the Indigenous African way of viewing God, which I call communotheism—God is the community. We can name individual deities, but they’re all connected to the one reality, the one thing that is God. God connects everything. To the extent that the Trinity represents that way of understanding God, I can agree with that.

What does salvation or eschatology look like through this theological lens? What is the end goal?

In my book, I talk about the word liberation and the way it has been critiqued. Starting with Cornel West: can liberation happen through capitalism, or is some other form of political economy necessary? Then I look at female writers who say that word is often framed through an andocentric lens and can often mean Black men trying to be liberated from white men. And what I argue is that any sort of liberation needs to include land: Earth needs to be part of our understanding, no matter what kind of political economy we create.

That’s where ecotheology comes in: What does liberation look like for the planet in relationship to this quest for racial justice, gender justice, etc.? So in terms of salvation, I definitely think of this strictly in an existential sense in terms of how we live together on the planet. There’s nothing otherworldly about this salvation, because, again, it involves a shift to the spatial and is very concerned about the now. The future is out there, but what does liberation look like in the here and now? For the world in which we live and the spaces we are trying to occupy and save?

What do you want your readers to take away from your book?

First, I want to rethink Christian theology to be more spatially orientated and focused on finding God in the spaces we occupy. I talk about God as cosmic energy and creative intelligence. It’s more of a panentheistic conception of God, in which we can access God at any moment. Albert Cleage uses the term “plugging into God,” where as a group we can collectively plug into God as a power source, as it were. I want to reimagine God who doesn’t just reside in one individual who lived 2,000 years ago.

I also want us to think about the history of white supremacy and racism in spatial terms and how land dispossession is part of this legacy. Obviously, systemic violence is a part of how we think about oppression, but it has also been the dislocation of space, specifically land conquest and land dispossession. The Transatlantic slave trade dislocated people, but there was also a second dispossession that happened after slavery, when African Americans who had acquired land had that land systematically stolen from them. Similar things happened to Indigenous communities around the world. I want to highlight and talk about the legacy of the failure to Indigenize space and what was lost. What has the legacy of colonialism wrought for the Earth? Is it related to the ecological crisis?

This article also appears in the April 2023 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 88, No. 4, pages 26-29). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

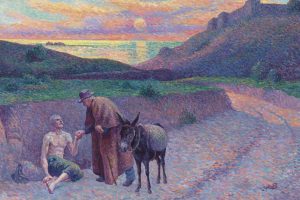

Image: Unsplash/Mladen Borisov

Add comment