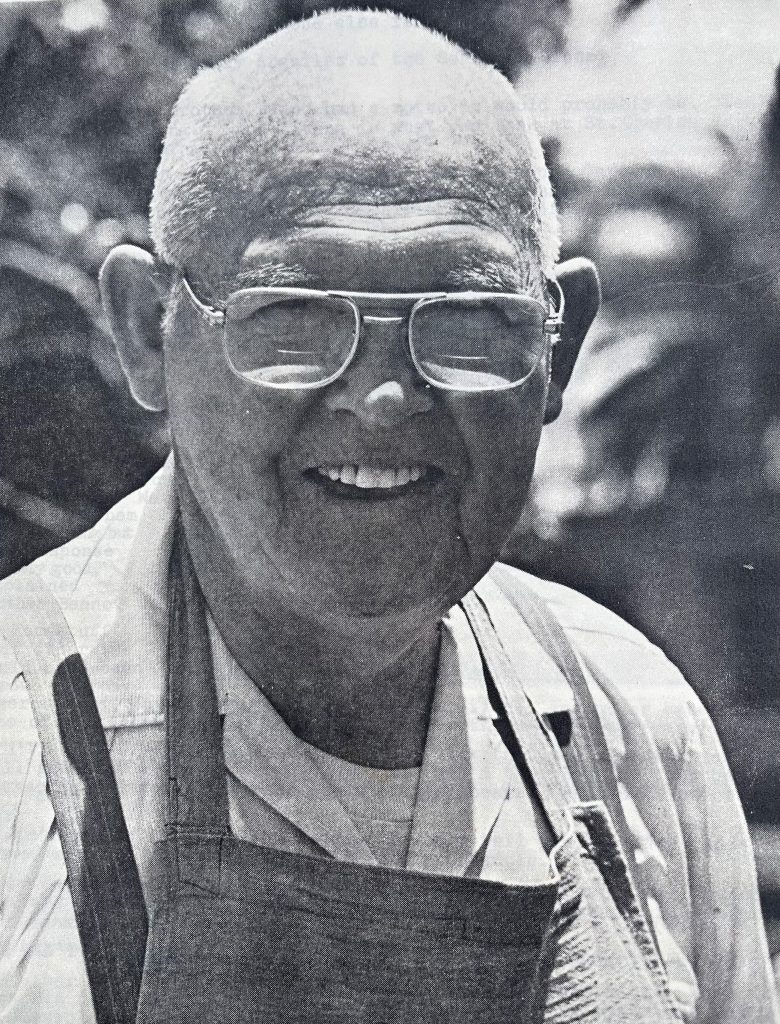

In 1967, Brother Benno Garrity arrived at the Prince of Peace Abbey in Oceanside, California. While he was sent to the monastery to retire, he quickly was drawn into caring for the needs of those in the surrounding community.

Garrity’s work was based in personal relationships, says Father Charles Wright, one of the priests at the monastery. He loved to bake bread, and after making a fresh batch he would personally deliver loaves to nearby shelters and food kitchens. Or he would drive around in his truck, picking up items that people discarded and bringing them to other locations where they were needed. He enjoyed cooking and repurposing items.

“He would make big kettles of beans or soup or whatever, and he’d go out to the fields where [migrants] were working and actually give workers food,” Wright says.

Garrity’s ministry might seem a bit odd for a monastic brother whose vocation is rooted in prayer and contemplation. But monastic life is always changing and responding to the needs of the communities in which they are located. Since the time of the Roman Empire, monasteries have served as social safety nets when empires and governments have failed to feed people who are hungry or to care for the marginalized.

The Benedictines, the oldest religious order in the Roman Catholic tradition, was founded by St. Benedict of Nursia in the sixth century. The Rule of St. Benedict, which is estimated to have been written between 530 and 540 C.E., provides guidance on Christian and monastic life. Over the centuries, from one nation to the next, the Benedictine order has found creative ways to meet the needs of the world around it.

Katie Gordon, who spent time among the Benedictine Sisters of Erie, writes on Monasteries of the Heart that a responsibility of a monastic is “to live the future now [and] embody the future we seek in our monasteries and communities.” Contrary to what many might think, a monastic life can mean engaging with the world and those living in it.

Today, the work started by Garrity in the 1960s has expanded. Prince of Peace Abbey is known in the community not only for its long-standing presence but also for its ministries throughout Oceanside. In keeping with their historical tradition, these ministries work to feed and clothe people who are often overlooked in the surrounding community.

Feed the hungry

While the Benedictine tradition is rooted in self-reflection and individual prayer, it also warns against neglecting the community around them. One way to put this into practice, according to the Rule, is hospitality, including inviting strangers into the lives of the monks and sisters. The goal is to welcome and treat each person as if they are Christ.

Such radical hospitality formed an important part of Garrity’s ministry. During his early years at the abbey, Garrity was moved by the presence of undocumented immigrants, many of whom were Mexican, who stumbled upon the abbey by accident, looking for food and shelter.

“There was no place for people to get food. They were hungry, you see. So Brother Benno was looking for a place for them, but he did much more than just feed them,” Wright says.

His hospitality soon went far beyond feeding individuals who arrived at the monastery. Harold and Kay Kutler were friends of Garrity’s who owned a vitamin business. They had originally met the monk when he brought Harold a loaf of fresh bread in exchange for some vitamins. After their retirement in 1983, the Kutlers sold their business and opened the Brother Benno Kitchen. While this soup kitchen was ecumenical, the spirit of the Benedictine tradition played a large role in shaping the ministry. The soup kitchen would eventually expand to become the Brother Benno Foundation and Center.

The mission statement of the Foundation is based on Matthew 25:31–45, where Jesus teaches that whatever anyone does to the poorest and most vulnerable, they do to him.

The foundation’s website states their mission simply:

- To feed the hungry!

- To give drink to the thirsty!

- To shelter the homeless!

- To clothe the naked!

- To comfort the sick and also to support people recovering from addiction!

Today, the Brother Benno Center sits about two miles from the abbey. The center is open daily and serves hot meals to all who need them. It provides a variety of services to the community, including offering food, showers, and clothing. It also has a recovery program and a thrift store and serves as a community hub where county social workers and caseworkers can assist unhoused people who may be dealing with a variety of difficulties and challenges.

The Center relies on funding from grants and volunteers, many of whom come from nearby Catholic parishes.

Father Stephanos Pedrano, a Benedictine priest and monk at the abbey, explains how the Center has evolved over the years: “It was a little more hands-on in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s when Brother Benno was still alive, collecting food from grocery stores and local farmers for us to use,” he says. “There was so much that he collected to give away to the poor.” And yet, although this work has grown far beyond Garrity’s original ministry, it serves as a legacy and extension of his mission.

Aid with recovery

Aside from offering food assistance, the Center also serves those struggling with addiction through the Brother Benno Men’s and Women’s Recovery Program.

During the 26-week transitional living experience, participants seek sobriety through complete involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous in exchange for serving clients at the center, the warehouse, or the thrift shop.

Jim Shlemmer, manager of the recovery program and a drug and alcohol counselor, speaks about a difficult day at work: A woman in the program had slipped in her sobriety and was in the middle of moving out of the house. Shlemmer says this is the reality of sober living houses.

Shlemmer himself went through the recovery program and now works for the Foundation alongside his father. For a while, he and his father were estranged, but when Shlemmer regained his sobriety they were able to reconcile. Today, both are involved with the ministry.

“Alcoholism is a disease that affects all demographics. There is help, and people do recover,” Shlemmer says.

A growing need

Between the proximity to the U.S.–Mexico border and a political climate that can make immigration a polarizing issue, the need for Catholic organizations to minister to immigrants has not disappeared. And the COVID-19 pandemic brought new challenges to the work of the Brother Benno Center and the Brother Benno Foundation, which runs the center.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the Center moved services outside. It also collaborated with Feeding San Diego, part of Feeding America, to create a weekly drive-through food service. Anyone could drive through the food warehouse, and volunteers would put a box of food in their trunk with no questions asked. The center had never done this type of outreach before.

When you visit the Foundation’s website, you can track the number of meals served, articles of clothing shared, showers taken, food boxes assembled—and, in memory of Kay Kutler, number of hugs given. (According to Harold Kutler, his wife’s hugs were a major contributor to the warmth and hospitality of the Center.)

Military ministry

Today, more than 50 percent of the people who come to the center are men between the ages of 30 and 44 without children. Many who are served, as in Garrity’s day, are immigrants. However, another growing population is also being ministered to in Oceanside: veterans and military families.

Oceanside is home to Camp Pendleton, originally established in 1942 during World War II to train Marines and today one of the largest Marine Corps bases in the United States.

According to the Military Family Advisory Network, 1 in 6 military and veteran families experienced food insecurity in 2021. A 2022 survey from the Military Family Advisory Network also revealed that more than 60 percent of those surveyed have difficulty affording housing.

There are a variety of reasons for this. Sometimes, only one of the Marine spouses is employed. Other times, the spouse does not have additional income, because they are busy caring for their children. Spouses can face difficulties finding jobs, because they are often required to move frequently. Larger families with more children may be especially at risk of hunger. These and other factors contribute to food insecurity among military families.

“A tragic reality is that our service men do not earn enough to support their families,” Pedrano says. The pandemic only made this insecurity worse, and military families at Camp Pendleton do not always have enough food or basic necessities. This is one need that the center is working to meet: They provide military families with food boxes and other supplies.

Passing on the torch

Whether feeding the hungry, ministering to those struggling with addiction, responding to global pandemics, or helping with food insecurity among veterans and military families, the monastic tradition of offering welcome and care for those left behind or forgotten lives on at the center, as does Garrity’s spirit. The model of service, however, has changed over the years. Today, the monks themselves do not work at the center, but they continue to help fund some of the center’s needs.

In an article for Global Sisters Report about a June 2022 conference of women’s Benedictine monasteries, journalist Judith Valente writes, “While change is inevitable, one of the most important functions of monastic life must not and will not change: that of bearing witness.”

She goes on to describe how the conference alluded to the role laypeople will play in continuing the Benedictine tradition. “Today, the energy in monastic life is coming largely from laypeople drawn to the timeless values of community, hospitality, humility, stability, simplicity, balance, consensus, prayer, and praise that monasticism stands for,” she writes.

The same holds true at Prince of Peace Abbey: While Wright and Garrity are examples of vowed members who responded to the community around them, today the leaders of the Brother Benno Foundation are all laypeople: People such as the Kutlers and Shlemmer.

While today’s issues may look different than those at the time of St. Benedict, who lived during the decline of the Roman Empire, the work of Benedictine monasteries and the spirit of their tradition continue to thrive.

This article also appears in the October 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 10, pages 26-31). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Header Image: Courtesy of Kathleen Diehlmann

Add comment