When Sheri Bartlett Browne started working as a Catholic health care chaplain, she realized that despite hospitals’ best attempts to support patients and families through the dying process, there was a disconnect between doctors and patients. “My patients often seemed to be struggling, whether they felt like they weren’t being heard or were just frustrated by the system,” she says.

Browne, who also teaches history at Tennessee State University in Nashville, a historically black university, realized that part of this disconnect was due to cultural differences among the doctors at the hospital in which she worked, most of whom were white, and the patients, many of whom were black. So she began studying cultural barriers facing black patients around end-of-life care and how these barriers are affected by centuries of marginalization and oppression against black communities.

One way to overcome these barriers, Browne says, is by integrating Catholic social teaching into medical care. Doing so, she says, “requires determining what it means for a doctor or hospital to approach patients as if everyone is, in fact, made in the image of God.”

What does Catholicism have to say about end-of-life care?

Traditionally, Catholic hospital ethics has existed apart from Catholic social teaching. Catholic health care systems have a set of ethical and religious directives around which they live and breathe and that deal with things such as prenatal care, issues around abortion, sterilization, and end-of-life care.

In the Catholic tradition, end-of-life is both care and also an ethical framework for understanding the dying process. Medically, the term end-of-life care encompasses a pretty wide range of services. It can be specifically medical, providing pain relief, for example, but end-of-life care is also educating patients and families about the dying process, providing spiritual and emotional and bereavement assistance, and helping people understand and get through the grieving process. In the health care setting, it’s always a team approach that involves nurses, the medical team, social workers, and chaplains.

Ethically, end-of-life tends to focus very heavily on what it means to support life from natural birth to natural death, and it is often connected to the concept of dignity of the human person. Because of this, there’s a heavy focus on autonomous decision-making, or how to help someone make moral and ethical decisions about the dying process by providing them with information and support so they can decide what is best for them. This happens within a particular moral framework. For example, within the Catholic tradition, autonomy and dignity do not support physician-assisted suicide.

The traditional bioethics approach sees everyone as an autonomous individual instead of as relational, as living in community. That relational approach is found in the Catholic social tradition. If we’re even going to think about social justice within a health care setting, then we need to bring these bioethical directives together with the Catholic social tradition. Only then can we consider what is good and ethical and just for everyone.

To incorporate Catholic social justice into the ethical and religious directives that drive a lot of decision-making in health care, you need to consider a person’s historical, cultural, and religious context. Because how else can you help them make decisions about their death or inform the medical team as they help make decisions?

Can you give an example of where Catholic bioethics falls short?

Among African American patients, community is really important. There are often cousins, aunts, uncles, and friends at a patient’s bedside supporting them and thinking about their loved one’s dying process.

The emphasis on a patient’s autonomy, which is what is traditionally done in Catholic ethical approaches to dying, is very much due to a Western, individualistic view of the self and of dying. This view misses the importance of the family interacting with their loved one.

This can cause a lot of frustration for both medical teams and families. For example, if a patient has had a severe brain injury, a common procedure is to test for brain death. But oftentimes families don’t understand what the medical team wants to achieve. They become frustrated or angry and feel like their loved one is not being cared for appropriately.

From the medical team’s perspective, this is a medical decision, not an emotional one. It’s a decision based on tests, whether there’s any brain activity, whether the patient is going through organ failure, and other tests. If there is no brain activity, then the patient is dead already and they are ethically bound to remove life support.

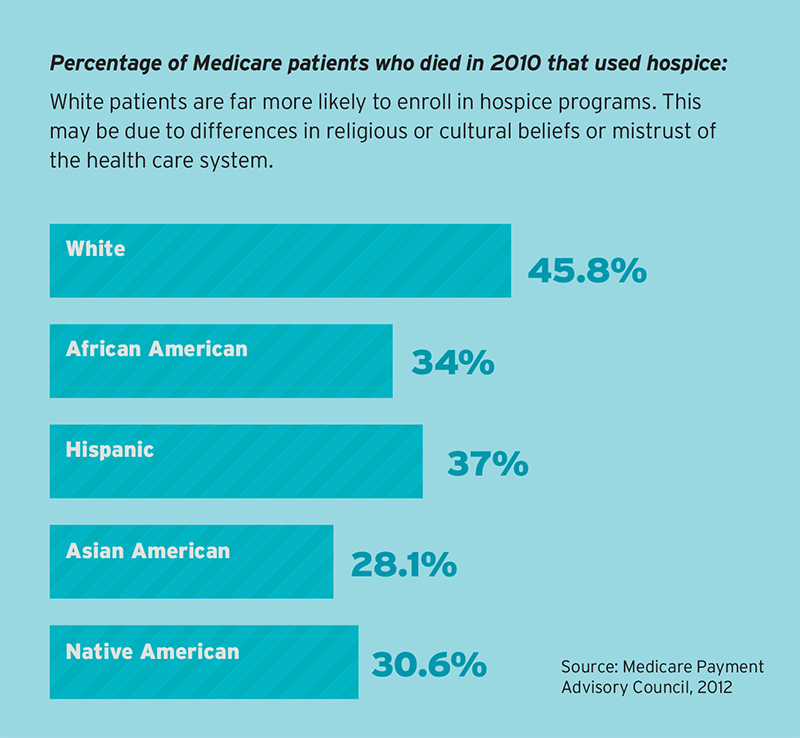

But for families, if someone is on life support and breathing with the help of a ventilator, then they are still alive. This is true in any family but becomes even more fraught in many African American families because there’s a lot of mistrust of the medical community already. The African American community has experienced a lack of health care and undergone medical experimentation without their consent. So in a situation this fraught with emotions, it’s not just a straightforward medical decision for them.

To help families get through this experience, hospitals need to incorporate Catholic social teaching, not just act from their ethical directives. It’s important to consider the totality of a person and their situation.

Can you give a historical example of why African Americans mistrust the medical establishment?

The Tuskegee syphilis experiment lasted 40 years, from 1932 to 1972. The study involved 400 men in Macon County, Alabama who tested positive for syphilis and who were studied to see what would happen over the course of the disease. During that 40-year period, antibiotics became available to treat syphilis, but these men were not offered antibiotic treatment. Today, Tuskegee is seen as one of the most egregious experiments on a living population in the 20th century.

Though 1972, when the study ended, seems like a long time ago, there are many people alive today who remember hearing about it or who had family or friends who were affected. It’s still very much a tangible experience in the historical memory of African Americans, and it continues to have a lasting impact.

Today, when pharmaceutical companies test a new drug or treatment, they ask many people to participate in research studies. But black participation in such studies is quite low, and researchers attribute that to things such as the memory of Tuskegee, along with other forced medical interventions: the long history of the forced sterilization of African American women and neurological experiments that were done on African American children.

Black people today are not confident that they will be treated in the same way a white person would be if they’re asked to participate in a study or take a new experimental drug. I even had someone tell me that the memory of Tuskegee is enough to affect how they think about their own routine health care.

How does Tuskegee still affect attitudes toward health care today?

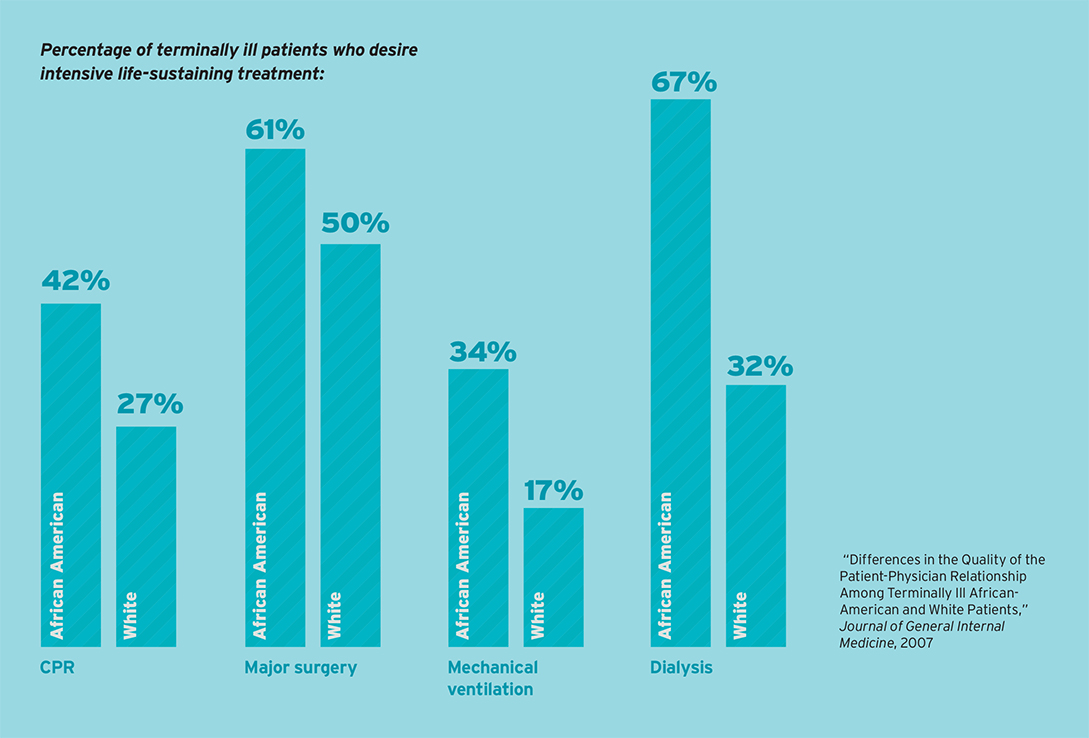

Take advance directives for example. In many white communities, signing an advanced directive is considered fairly typical; people believe it will prevent unwanted or aggressive care at end-of-life. They have an understanding of CPR and what it can do to a patient’s body, especially if they are older or frail, and they often will say, “I don’t want that. Let me sign the forms.”

But among communities that have been marginalized, or have not received care when they needed it, or did not give informed consent to something like in the Tuskegee experiments, signing a form like this that talks about those very last minutes at the end of your life is a lot more problematic.

People think that it means they’ll be neglected at the end of their life, that doctors won’t try to save them and will just stand by doing nothing and watch them die. There’s a fear that patients won’t get pain medication or assistance with breathing and that they will be in pain and suffering while people do nothing to stop it.

What does culturally sensitive end-of-life care look like?

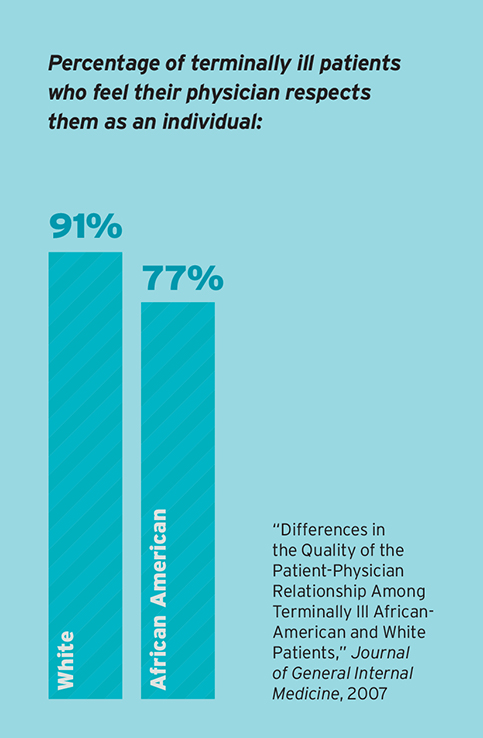

As a chaplain, I am often with families as they go through the death of a loved one. What I see time and again is that medical teams are often rushed; they’re doing the best they can and certainly want to reach out to family members, but they also have a lot of demands on them. They’ll explain what they want to do medically or what test they’re going to run, but they’re not very good at explaining it while bridging any cultural, educational, or socioeconomic divide.

I feel like because of this they often get frustrated. They’ll tell me that whoever they’re talking to, a patient or their family, just doesn’t get it. Doctors will say, “This is what we need to do next. We’ve come to the end of the line, and we need to do a test for brain death. I’ve explained all this to them, and I don’t understand why they’re pushing back.”

This is often when the chaplain is called in: when doctors have made this decision and they’re meeting resistance from the family that they don’t understand. The chaplain then has to come in and explain what’s happening next not medically but to facilitate emotional and spiritual understanding and help lessen the anxiety in the room.

Doctors are so intent on delivering their own message about what needs to happen next that they don’t understand the process from the perspective of the family members gathered there.

More awareness, education, and training for doctors and medical professionals could definitely help these kinds of situations. Because when there’s already a socioeconomic or cultural barrier, this is really heightened in these life-or-death moments. If doctors had a better understanding of these cultural factors, it could help lessen the tension and help family members better understand what’s happening.

How do hospitals start to implement this approach?

First, hospitals and health care systems need to completely revamp their cultural awareness or cultural sensitivity training. Right now, this training normally lasts an hour or maybe a half day. It’s framed as “come and learn these things to overcome a problem.” Employees learn about culturally appropriate behavior, such as how a male doctor should interact with a female Muslim patient, things like that.

Instead, this training should be taught by providers who work with specific communities. It should take into account not just behaviors but also people’s mindsets and beliefs.

I also think medical practitioners, chaplains, social workers, whatever the role, should get much more immersion training with underserved communities. This should last not just for a day

or a week, but should be a substantive part of people’s medical training and experience.

We also need to aggressively recruit diverse medical practitioners. We have a huge shortage of black physicians, for example; hospitals should be working much harder to remedy that.

Finally, we need to change the mindset that working with underserved communities is somehow less prestigious or deserving. Right now, medical schools are funneling people into neurosurgery or cardiac. There’s a shortage of good family doctors or general practitioners. We need people who are just as talented to serve in the neighborhood clinic.

Image: Jair Lazaro on Unsplash

This article also appears in the April 2019 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 84, No. 4, pages 18–22).

Add comment