Fifty years ago this past July, Pope Paul VI issued his landmark encyclical Humanae Vitae (On the Regulation of Birth), which reaffirmed the church’s teaching against the use of artificial contraception. The encyclical shocked Catholics who had been expecting a change in the church’s position.

The backlash to the encyclical was immediate, widespread, and—for a papal document—unprecedented. Prominent Catholic magazines editorialized against it. Theologians signed statements questioning its theology. Even some bishops were critical, and many others were decidedly muted in their support.

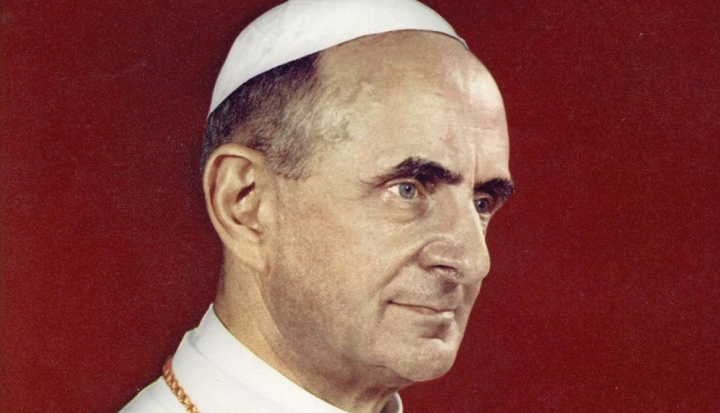

Half a century later, Paul’s reputation is still bound up with his most well-known document. Earlier this year the Catholic magazine Commonweal published a retrospective on Humanae Vitae with a portrait of Paul VI under the headline “An Unhealed Wound.”

Yet as his cause for canonization has advanced (it is widely expected that he will be “raised to the altars” this fall), a reassessment of Paul’s legacy is underway. Conservative Catholics who were some of his fiercest critics in the tumultuous ’60s and ’70s now praise him for standing firm against proposed changes to church teachings on contraception, priestly celibacy, and the ordination of women. Catholics of a more liberal bent increasingly realize that Paul deserves credit for the successful implementation of many of the reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

Tested by war

Paul VI began his life in 1897 as Giovanni Battista Montini, the son of an Italian parliamentarian from northern Italy. His bishop, worried about his health, sent him to study in Rome, where he eventually entered the Vatican diplomatic service. After a brief posting in Poland, Montini returned to Rome. He rose quickly and became a senior official in the Vatican’s Secretariat of State.

That post gave him the opportunity to shape the Vatican’s response to the human devastation of World War II. As thousands of letters began pouring into the Vatican seeking help in locating displaced persons, Montini organized a staff group to coordinate the flow of information from Vatican diplomatic offices across Europe. In some cases names were broadcast on Vatican Radio in the hopes of surfacing information about their whereabouts.

Toward the end of the war Italy became a battleground between the Germans and the Allies. When fighting raged in central Italy, Pope Pius XII instructed Montini to open the papal residence at Castel Gandolfo to refugees. Some 12,000 were ultimately accommodated, including 36 babies born to pregnant women who sought shelter at the palace.

The pope of the council

Most Catholics associate Vatican II with Pope John XXIII, who summoned the council in 1959. But John died in 1963, a few months after the close of the council’s first session. It was left to Montini, who took the name Paul VI upon his election as pope, to shepherd it to its conclusion.

At the time of his election, Montini had been serving as the Archbishop of Milan, a post he had held since 1954. There he had developed a reputation as a cautious reformer, regularly visiting the city’s mines and factories to preach and celebrate Mass. While supportive in public, Montini had private doubts about Pope John’s decision to call the council. “This holy old boy doesn’t realize what a hornet’s nest he is stirring up,” he remarked to a friend.

Once installed as pope, however, Paul was quick to signal that the council would continue. He would guide it through three more sessions and hundreds of hours of debate. The council’s 16 documents reshaped the face of Catholicism. They called for a reform of the liturgy that would encourage greater participation by the faithful, a rebalancing of the relationship between the pope and the college of bishops, and greater dialogue with Jews, Muslims, and Christians of other denominations.

Equally important was Paul’s leadership after Vatican II, when the soaring language of the council’s documents needed to be translated into concrete action. Paul was willing to delegate more decisions to national conferences of bishops, such as how widely to use the vernacular in the liturgy. While he didn’t always agree with their decisions, Paul felt it important not to micromanage the work of the conferences unless core issues of Catholic doctrine were at stake. Paul also created the Synod of Bishops, a periodic gathering of bishops from around the world to advise the pope on important issues.

“This is your home”

One of the aims of Vatican II was to encourage the reunion of Christian churches that had become separated from one another over the centuries, a movement known as ecumenism. Pope John XXIII had invited Orthodox and Protestant churches to send observers to Vatican II. Hopes for reunion shaped both the council and its immediate aftermath in important ways.

Paul VI supported dialogue between the churches aimed at resolving doctrinal differences. He also had a talent for the dramatic gesture that could help break down centuries of mistrust. In 1964 he traveled to Jerusalem to meet with Patriarch Athenagoras I of the Greek Orthodox Church. The two signed a joint declaration and lifted the mutual excommunications that had triggered the Great Schism between Eastern and Western churches in 1054.

Paul’s most poignant act in support of ecumenism occurred during a visit to Rome by Michael Ramsey, the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, in 1966. Paul greeted Ramsey in the Sistine Chapel with the words “this is your home, where you have a right to be.” The next day, after they had celebrated an ecumenical prayer service, Paul asked Ramsey to remove his ring. When he did so, Paul placed the ring he had worn as Archbishop of Milan on Ramsey’s finger. Ramsey burst into tears, and the two men embraced. Ramsey wore the ring for the rest of his life.

“If you want peace, work for justice”

Paul will also be remembered for his interest in the plight of the poor in the developing world. Paul knew that the grinding poverty in many of these nations was often a seedbed of revolutionary violence. In 1968 he initiated the tradition of celebrating January 1 as the World Day of Peace. In his inaugural address he argued that peace is not merely the absence of conflict but the presence of justice, coining the memorable phrase “if you want peace, work for justice.”

Paul also made structural changes within the Vatican to give more voice to these concerns. In 1967 he established the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, among whose purposes was “to promote the progress of poor countries and to encourage social justice among the underdeveloped nations.” He also made a concerted effort to bring more voices from the developing world into the College of Cardinals. In his 1976 consistory a quarter of the 20 new cardinals hailed from Africa.

The hand of Paul could also be seen in the increasing engagement of national conferences of bishops on matters of justice. Paul’s involvement in this work dates back before his pontificate. He supported the efforts of Father (and later Archbishop) Hélder Câmara in 1952 to establish the first national conference of Brazilian bishops and, in 1955, a council of bishops for all of Latin America known as CELAM. Many of the ideas first voiced by CELAM in the 1960s and ’70s, such as the “preferential option for the poor,” have since become mainstays of Catholic social teaching.

Holding the center

The waning years of Paul’s pontificate were not easy. At the same time that he was contending with widespread dissent over Humanae Vitae he was also facing down a looming traditionalist schism led by French Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre. Lefebvre rejected Vatican II’s reforms to the liturgy and its teachings on ecumenism and religious liberty. He established a seminary in France and began ordaining priests despite being forbidden to do so by Rome. Paul’s repeated efforts to bring Lefebvre back into the fold of the church proved unsuccessful.

Paul’s tendency to seek common ground between various factions and to agonize over major decisions led many to see him as indecisive. In a private note to a friend in 1978 he wrote, “Am I Hamlet? Or Don Quixote? On the Left or on the Right? I do not feel I have been properly understood.”

That year would include a cruel final blow to Paul in the form of the assassination of his friend and former Italian prime minister Aldo Moro. Moro was kidnapped in March by the Red Brigades, an Italian terrorist group. While the Italian government refused to negotiate, Paul made a personal appeal to Moro’s captors and even tried to raise money for a ransom. On May 9 Moro’s bullet-ridden body was found in the trunk of a car in Rome. Paul was devastated by his inability to prevent his friend’s death. While at his summer residence at Castel Gandolfo, he suffered a massive heart attack and died on August 6.

Paul VI was never beloved like John XXIII and lacked the evangelical self-confidence of John Paul II. One need not agree with all his decisions, however, to recognize that he was truly a pontifex, a bridge-builder, who tried to maintain communion among Catholics with deep theological differences at a very challenging time. He did not always succeed. But in a church where increasing polarization sometimes seems to strain the bonds of our unity, Paul VI may be the saint whose intercession we most need right now.

This article also appears in the October 2018 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 83, No. 10, pages 25–27).

Add comment