Seated in a circle on sofas and easy chairs at a church rectory in a largely Hispanic section of South Bend, Indiana, a group of students from Notre Dame University and Holy Cross College train their eyes on a whiteboard. Scribbled in blue marker are the headings “Corporal Works of Mercy” and “Spiritual Works of Mercy,” along with quotes from Catholic Worker founder Dorothy Day and Trappist monk and spiritual writer Thomas Merton.

It is part of a student retreat sponsored by Holy Cross College Campus Ministry and the Catholic Peace Fellowship, an organization that dates back to the early 1960s and that is deeply influenced by Day’s and Merton’s writings on peace and nonviolence.

“The beginning of all peace work is prayer,” says Shawn Storer, director of the Catholic Peace Fellowship. He’s a bearded man with a shock of wavy hair, and he’s dressed in a denim shirt and green sweater vest. At 40 he looks barely older than the college students he is addressing.

The discussion centers on the hunger for meaning, engagement with people on the margins of society, and what the gospels teach about nonviolence. At the retreat’s end some of the students head to a Spanish-language Mass. Then it’s on to do some painting and repair work at Our Lady of the Road, a Catholic Worker-run facility that offers food and fellowship to South Bend’s homeless population.

About a month after this Peace Fellowship retreat, on the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s assassination, seven peace activists clipped a lock and broke into the Kings Bay Trident nuclear missile submarine base in St. Mary’s, Georgia. The seven, all members of the Plowshares peace group, carried hammers, banners, crime scene tape, and baby bottles of their own blood, which they splashed on a Navy insignia.

“We come in peace. We are unarmed and wish you no harm,” one of the protesters called out.

All seven were swiftly caught. Among those arrested were Elizabeth McAlister, the 81-year-old widow of the famous peace activist Philip Berrigan, and Dorothy Day’s granddaughter, Martha Hennessy, a 62-year-old grandmother of eight. Each protester was charged with trespassing and defacing government property and spent months in jail on $50,000 bonds.

Hennessy called the event “an act of atonement” for the U.S. stockpiling of nuclear weapons. Patrick O’Neill, 61, another of the Plowshares protesters, described it as “putting prayer into action.”

The Catholic Peace Fellowship and Plowshares (the name refers to Isaiah’s command to hammer swords into plowshares) represent different points on a spectrum of Catholic peace activism. Acts of civil disobedience, like the break-in at Kings Bay, the world’s largest nuclear submarine base, were once common during the Vietnam War and the arms race.

While nonviolence remains at the heart of gospel teaching, peace advocates today are debating what the church’s future direction should be. Should there be more widespread public actions, or do protests and demonstrations merely reinforce divisions? Should the focus be on education and personal transformation? Some activists even question if there is still a “Catholic” peace movement.

“Generally speaking, we don’t have a movement,” says Tom Cornell, a Catholic pacifist who headed the interfaith Fellowship of Reconciliation until 1979. The Nyack, New York-based organization once had 30,000 members but has about half that number today.

Cornell cites an American society anxious over terrorism and numbed by 17 years of continuous wars. “We organized one of the largest peace protests in history on the eve of the Iraq invasion. What good did it do? Nada, nothing,” Cornell says. Now 84, Cornell laments that few students he meets recognize the names of Day, Merton, or the Berrigan brothers. (Philip Berrigan died in 2002; his brother Daniel, a Jesuit priest, died in 2016.)

By contrast, the Plowshares protesters (the average age is 62) are still deeply influenced by the Berrigans, who drew international headlines 50 years ago with such high-profile acts as burning draft records at a Selective Service office in Catonsville, Maryland and splashing blood on the Pentagon. Plowshares members see public acts of civil disobedience against war and nuclear weaponry as a necessary part of the Christian witness.

Maria Surat, coordinator for community-based learning at Holy Cross in South Bend, who co-led the student retreat, says such “direct actions” like the Plowshares protest aren’t the focus of her peace work with young adults. Still, she adds, “There is space for that kind of prophetic witness.”

Peace work is also now more closely aligned with other efforts, including eradicating poverty, working for racial justice and gender equality, and care of the environment, says Ethan Vesely-Flad, who currently leads the Fellowship of Reconciliation.

“Because we are living in a state of perpetual war, it’s easy for people to think we’re not doing anything” to foster peace, Vesely-Flad says. “That isn’t true.”

Peace in action

Storer, the Peace Fellowship director, is the son of a Vietnam veteran and the first male in his family not to serve in the military. He attended college on a scholarship from the Vietnam Veterans of America specifically to study peacemaking. He, his wife, and their five children live on a farm where they grow much of the family’s food. He says most years he earns just enough to avoid paying federal taxes, which would go toward supporting military weaponry.

Storer sees his mission as doing “the more colorless apostolic work” of teaching young Catholics to practice nonviolence in daily life. “Peace is a person. That person is Jesus Christ,” he tells students.

One of Storer’s mentors is Catholic Peace Fellowship’s cofounder, the spiritual writer Jim Forest. Forest now lives in the Netherlands but was active in anti-war and civil rights protests when he lived in the United States. He says a different approach is needed in the era of Trump.

“It’s a time for pray-ins,” Forest says. “It’s not a time to get out in the streets and create a climate of greater rage. It adds to the polarization that is one of our major problems.”

Like Storer, Forest says he believes works of mercy and the cultivation of a more prayerful, meditative way of life provide important paths to peace. “One of the most important aspects to peacemaking is love of enemies,” Forest says. Travels with the Buddhist Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh, he says, taught him that peace begins in the heart.

“Learning to walk more slowly, learning to breathe more mindfully, to take unwelcome tasks, like washing the dishes and waiting in line in the supermarket, and make them into sacramental events, praying instead of grumbling,” Forest says. “It makes you an island of peace.”

Members of Plowshares say a focus on prayer and works of mercy is not incompatible with direct actions, like the one they staged at the nuclear submarine base.

“What Shawn Storer is doing is beautiful and critical,” says Hennessy, who is under house arrest at her Vermont farm after being released on bond. “Both Shawn and I are abiding by the same principles.”

Hennessy recalls that her grandmother, Dorothy Day, would often say, “Cast a small pebble.” Each person has a pebble, Hennessy says. “We don’t have to cancel each other out.”

O’Neill, another of the Kings Bay protesters, says actions like the Plowshares break-in pique the public’s conscience, even though that protest garnered just five paragraphs on washingtonpost.com. He says his mentor, Philip Berrigan, would get arrested with other pacifists at the Pentagon long after newspapers stopped covering these demonstrations. Berrigan said he was trying to influence the Pentagon’s military personnel as much as the public.

“He would say, ‘We’re their only access to the truth. Catholic pacifists are the only ones saying no to the system,’ ” O’Neill recalls. Like Hennessy, O’Neill is out of jail on bond. He wears a tracking device when he brings communion to patients at a hospital near where he lives.

O’Neill’s 30-year-old daughter, Bernadette Naro, teaches at a Catholic high school in Atlanta. She says she’s found students react enthusiastically when given a chance to participate in peace efforts. Some of her students organized a “Torture Awareness Week.” They wore orange jumpsuits ordered from Amnesty International, similar to those worn by prisoners at Guantanamo Bay arrested after 9/11, and T-shirts that said “Who Would Jesus Torture?”

“These students were out before the sun even came up, standing outside, handing out leaflets to the car pool line,” Naro says. Another student group organized a campaign to pray daily for migrants. “When you give students something to sink their teeth into, they’re ready and willing to act,” Naro says.

Still, she says her students were surprised by some of the backlash they faced from members of their community. “It was a good opportunity to teach them why being prophetic often comes with a cost,” Naro adds.

Forming activists

Storer says that young people who’ve come of age in the era of Snapchat and Instagram are inspired by individual and symbolic actions but aren’t necessarily interested in collective movements. “As we work with young people, we see just how individualized their lives and upbringings are, so the idea of a movement is somewhat foreign to their imaginations because the collectivism we live in is a collectivism of individualism. Fragmentation marks our lives,” he says.

Dylan Maugel, a sophomore at Holy Cross College, is one of the Peace Fellowship students who says he is more interested in helping on a local level than trying to tackle large international peace issues. One day a week he volunteers to serve breakfast, wash the clothes of the homeless, and clean the showers they use at the Our Lady of the Road Catholic Worker center.

“I see injustice in the community, and it breaks my heart. I felt a calling to help give human dignity to all, especially those on the margins of society,” Maugel says.

He says young people his age care about “injustice in third-world countries and also the violent age of war we are in,” but adds that he believes it is most important to address the injustice that is “present right around us.”

Catholic Peace Fellowship also tries to change hearts and form consciences, one person at a time. It has, for example, an active ministry to soldiers seeking conscientious objector status and those dealing with the post-traumatic stress of combat.

Daniel Baker, 31, is a former Navy SEAL who became disillusioned flying reconnaissance missions over Iraq and the Arabian Gulf. “Our primary mission was to kill the enemy, not to defend the innocent,” he says.

Baker reported his qualms to his Navy chaplain but says he received little support. He searched the internet for information about conscientious objectors and discovered the Peace Fellowship site.

“I’ve been unable to detach myself from the place and the people since,” says Baker, who now works as a carpenter and is discerning a call to the priesthood.

The Peace Fellowship also proved a life-changing experience for Michael Thomas, 28, a Congregation of Holy Cross seminarian. As a teenager growing up in South Bend, Indiana, Thomas says he cheered news of the American invasion of Iraq. He believed the war was justified. That changed after he wandered into a Catholic Worker house in South Bend one day when he was home from college and looking for a place to attend Mass. From Catholic Worker he learned about the Peace Fellowship.

“We are forming young people to know what the church actually teaches about war and peace,” Thomas says of the Peace Fellowship. “The stance of the church has always been a lament over war because war represents a moral failure, even if it is deemed to be just.”

Baker and Thomas acknowledge it can be a hard sell to get people in their 20s and 30s engaged in peace work. There is no draft as there was in the Vietnam era; the U.S. military is made up of volunteers. For that reason war has become a “far-off norm” for many young people, Baker says. “It doesn’t affect us; it’s a meaningless kind of thing.”

Papal messages

Still, Catholic peace advocacy seems poised to enter a new phase—one refocused on gospel teachings rooted in nonviolence. Ken Butigan is a peace studies lecturer at Chicago’s DePaul University and consultant to Pace e Bene, an international peace organization. That group, along with Pax Christi International and the Vatican Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, organized a 2016 summit in Rome focused on nonviolence.

“It was a powerful experience where we heard from people living in very violent situations,” Butigan says. The conference ended “by issuing a call to the church to recommit to the centrality of the gospel of nonviolence.”

Pope Francis later focused on nonviolence in his 2017 World Day of Peace message. “Countering violence with violence leads to forced migrations and enormous suffering,” the pope said at the time. Nonviolence, he added, must be the “hallmark” of our decisions, relationships, and actions.

Butigan and other peace scholars are now working with Vatican officials on what they hope will become a document Pope Francis issues providing a comprehensive theological grounding for nonviolence. Its aim would be to have as much international impact as the encyclical Laudato Si’ (On Care for Our Common Home), in which the pope raised care of the environment to a moral imperative.

“We’re in the fix we’re in because we really have not embraced the nonviolent option as a country, or even as a church in a lot of ways,” Butigan says.

Whether the pope issues such an encyclical remains to be seen. Meanwhile Butigan says he sees value in Catholic pacifists using “a spectrum of approaches.” Challenges to war and injustice can be “active, engaging, and sometimes even confrontational,” like the Plowshares protest, as long as they remain nonviolent, he says.

What is most important, Butigan notes, is for the church to spark a conversation that challenges conventional perspectives on war and underscores “nonviolent options as an integral part of our faith.” A papal encyclical, he says, would go a long way toward achieving that goal.

This article also appears in the September 2018 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 83, No. 9, pages 28–33).

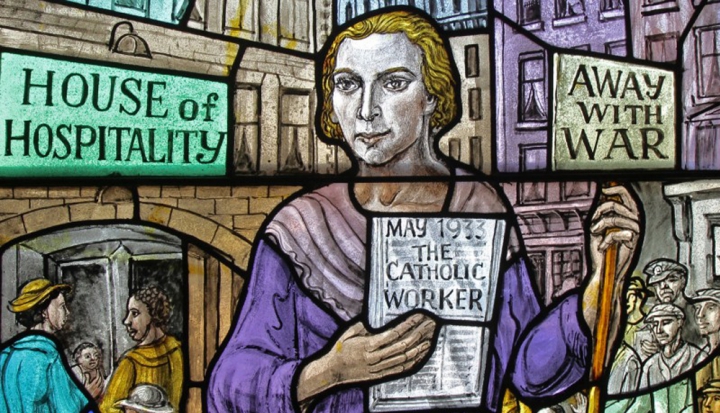

Image: Dorothy Day portrayed in a stained glass window at Our Lady of Lourdes Church in New York City. Flickr cc via Jim Forest.

Add comment