If your hand or foot causes you to sin, cut it off and throw it away! If your eye causes you to sin, pluck it out! It is better, we are told, to live blind and maimed than to be thrown into “fiery Gehenna” with all our body parts intact (Mark 9:42–48, Matthew 18:6–9).

What are we to make of Jesus’ teachings? They seem pretty clear. However, interestingly enough, the Catholic Church would consider it a mortal sin if someone with sound mind willingly engaged in the sort of self-mutilation Jesus recommends.

Now, let’s get that straight: If someone were to obey the seemingly clear teaching of Jesus about the benefits of self-mutilation for the good of one’s soul, it would actually be a mortal sin! The church interprets these verses as an example of Jesus using extreme exaggeration in order to teach a lesson. In this case, Jesus is emphasizing how important it is to worry about how our actions affect our eternal life with God, not literally telling us to cut of our own limbs.

I am certainly not attempting to undermine the authority of scripture or to challenge Christ’s teachings. What I am trying to point out is that when using scripture to guide our moral lives, we almost always have to enter into a process of interpretation. And this process is not always as clear as we would like it to be.

Some Catholics (including some bishops and cardinals!) have appealed to scripture to justify their positions on whether divorced and remarried Catholics can ever receive communion. The Extraordinary and Ordinary Synods on the Family held in Rome last October and this month, respectively, have garnered a great deal of press coverage because of these debates. But do these positions remain true to the tradition of biblical interpretation?

The first thing that needs to be recognized is that nowhere does Jesus explicitly address the topic of who may or may not receive communion at a Catholic Mass. This seems like such an obvious point; however, one doesn’t need to read too many of these debates to find that some on both sides seem to forget this fact. Let’s take a look at some of those scriptures that are seen as relevant to the debate.

Those who argue for a more “merciful” or “pastoral” approach appeal to the scriptures where Jesus spends time with sinners, sharing meals with them and causing scandal with the religious leaders of his time. One might look at passages like Mark 2:17, Luke 5:30–32, or Matthew 9:12 where Jesus tells the Pharisees, “Those who are well do not need a physician, but the sick do. Go and learn the meaning of the words ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice.’ I did not come to call righteous but sinners.” When the Pharisees and Scribes complain that Jesus welcomes sinners, Jesus responds by telling them the parables of the Lost Sheep, Lost Coin, and Prodigal Son (Luke 15:1–32). Jesus tell us that those who expect to enter into the Kingdom of God may be cast out with “wailing and grinding of teeth” while “the last shall be first” (Luke 13:22–30). When Jesus encounters a woman accused of committing adultery, he does not condemn her, but tells the gathered crowd “let the one among you who is without sin be the first to throw the stone at her” (John 8:7). Violating the social restrictions of his time, Jesus speaks with a Samaritan woman at a well despite the fact that she has had five husbands and the man with whom she currently lives is not her husband (John 4:4–42).

Of course, none of these passages explicitly deal with who may receive the Eucharist. However, many find it difficult to reconcile this image of Jesus with the position that no divorced and remarried Catholic may ever be allowed to receive communion under any circumstances.

On the other side of the argument there is just as much biblical justification. In Mark’s Gospel, Jesus explains that even though Moses permitted divorce, this was not God’s plan. Jesus tells the Pharisees that “what God has joined together, no human being must separate” (10:9). Later, Jesus privately tells his disciples, “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery against her; and if she divorces her husband and marries another, she commits adultery” (10:11–12). In Paul’s letter to the Romans (7:1–3) we are told that a woman must not consort with another man as long as her husband is alive, lest she become an adulteress.

None of these passages mention communion either. But the reasoning goes that because a divorced and remarried couple is understood to be in an ongoing state of adultery, they should not have access to the grace available in the Eucharist until they have abandoned their adulterous relationship (or at least committed to sexual abstinence for the rest of their life together).

Those advocating for greater leniency on who may receive communion are not arguing that the marriage covenant can be dissolved (which is a matter of church doctrine), but only that there may be some circumstances that allow a couple to receive communion (a matter of church discipline). However, church doctrine and discipline are intimately connected. A change in church discipline can affect how one understands doctrine. Even though no one is advocating a change in doctrine, the understanding of how the church interprets scripture and applies this interpretation in its teaching on the indissolubility of marriage is not as clear cut as many seem to believe.

For example: Matthew’s gospel (19:1–12) also tells us that to divorce and remarry is to commit adultery; however, there is an exception if there is porneia. In the various English translations of the Bible, this word might be translated to mean “lust,” “unchastity,” “unfaithfulness,” “wantonness,” “fornication,” “incest,” or simply if the marriage is “unlawful.”

It seems that there is a biblically-based exception to the teaching about the indissolubility of marriage and we are not even sure what that exception is. What does this word mean? In light of the ambiguity, where does the benefit of the doubt go? Should we introduce a certain humility in the way this teaching is interpreted and applied?

Does the church even teach that marriage is indissoluble? Actually, no. You may or may not have heard of “Privileges of the Faith,” or Pauline and Petrine Privileges. The Pauline Privilege, based on the First Letter to the Corinthians (7:12–15), allows for the dissolution of a marriage between two unbaptized people if one of them becomes Christian.

Confused? Suffice it to say that nowhere in the gospels does Jesus provide for this exception to his teaching about marriage and adultery. The description of this can be found in the Code of Canon Law (1143). Therefore, The Pauline Privilege represents a particular interpretation of 1 Corinthians and then an application of this interpretation to a specific pastoral circumstance.

There is another “Privilege of the Faith” sometimes called the “Petrine Privilege.” It involves a baptized Catholic who married an unbaptized person (with permission from the church) and now wants to marry another Catholic (or other baptized Christian). In these circumstances, the pope can “dissolve the marriage bond.” Is this situation addressed in scripture? Of course not. This exception represents another instance where the church is interpreting the spirit of the scriptures and then applying this understanding to a specific pastoral situation.

The church teaches that the only marriages that are indissoluble are sacramental marriages that have been consummated. Now, Jesus didn’t talk about “sacramental marriages” or “consummation” when he addressed remarriage and adultery in scripture. But, the church has done what it has always done (and always can do); seek the guidance of the Holy Spirit in interpreting the scriptures and applying these interpretations to specific pastoral circumstances. There is no reason that the same process of interpretation shouldn’t continue today.

Father Paul Keller’s online column, Smells like sheep, focuses on the places where pastoral ministry, public policy, theology, and ethics converge.

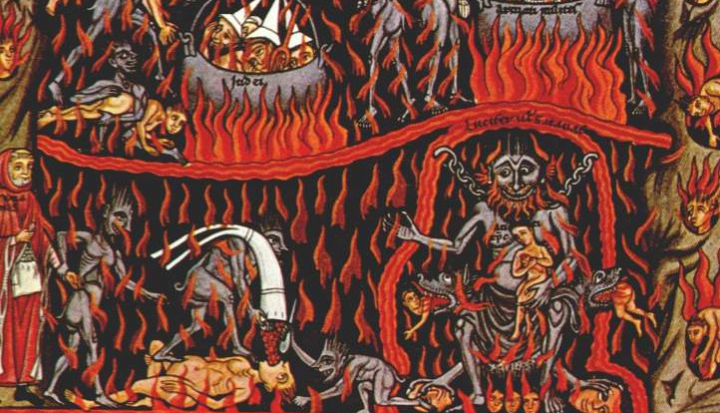

Image: Hortus Deliciarum, ca. 1180, Herrad of Landsberg. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.