By grieving with the Blessed Mother, we comfort all mothers who mourn.

In my hometown of San José de Gracia in Jalisco, Mexico, church celebrations marked the pace of our lives. Though liturgical reform took time to arrive, the practices of popular Catholicism kept our faith alive and active. These celebrations belonged to the people—to our mothers and fathers, to our ancestors, and to our rezanderos (laypeople who lead the prayer).

Good Friday was of special importance to us. At home we began by fasting, because according to my mother’s personal theology, “These days are really big.” We wouldn’t listen to the radio or play games. Rather we were silent and participated in the Stations of the Cross, the service of the Seven Last Words at 3 p.m., and then the Liturgy of the Word with the reading of the Passion. But the center of the day for me was the Pésame, a ritual of offering condolences to the mother of Jesus.

My mother would take my younger sisters, older brother, and me to church for a second time on Good Friday to be with the Madre de Dios because she was going through an unspeakable pain. Her son had just been publicly humiliated, abandoned and denied by his closest friends, tortured, and finally crucified. Now she was alone.

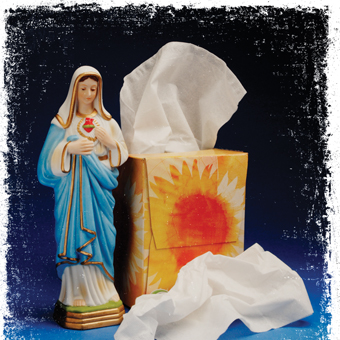

We honored her as Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, Our Lady of Solitude. But she was also called La Dolorosa, the Sorrowful Mother. At church we prayed the rosary, and our pastor would lead us in a deep reflection about Mary’s pain and her fidelity to God’s plan.

We gathered near her statue at the right side of the altar, in front of her son’s dead body. We were there to be with her, to console her, and to offer our deepest condolences. We did not touch her image out of respect for the sorrow she was going through. But we loved her then as we love her now. We saw and experienced her as Jesus’ companion in our salvation.

The Pésame began in what we now call Guatemala, brought by St. Pedro José de Betancourt, whom Pope John Paul II canonized in 2002. Around 1670 he began processions with the Nazareno (an image of the suffering Christ) through the streets of old Guatemala City. Christ’s body was extremely scourged, with no place for even one more wound. The people were impressed with this image because according to their story of the creation of the world, Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent, had to pierce himself to water the earth. As a result of this watering, human beings were born. This wounded Jesus, the new God introduced to them, really knew their pain and suffering.

But they also knew that Jesus had a mother whose pain had to be honored and healed, and in a short time this tradition expanded to Mexico and El Salvador and became what we now call the Pésame.

Celebrating Pésame is not a matter of words but of presence. It is not what we say but what we do with our whole being. It is the way we see the suffering of our world through the prism of the cross. We reflect on how that suffering wounded not only Jesus but his mother, all his followers, and finally each of us as well.

In our world there are many mothers whose children have been killed, both in Iraq and in our barrios. Those children have died in car accidents and crossing the border. They have been crucified by AIDS, by cancer, or by a drunk driver. Their mothers are also alone, but we often fail to offer our prayer and our solidarity. We deny them pésame.

At San Fernando Cathedral in San Antonio, a new tradition has been born. After the rosary, instead of one of the ministers sharing a reflection about the Sorrowful Mother, a real mother who for whatever reason has lost one of her children offers pésame to La Dolorosa on behalf of the whole church. Together they know what it means to lose a child.

Margarita Hernández also knows that pain. She is from my hometown, and as a kid I played soccer with Raúl, her third son, who died in a fall from a building. Four years later her fifth son, Fernando, died in a car accident. Who better than Margarita to offer healing to Mary for such pain, and who better than Mary to heal Margarita?

This article appeared in the April 2007 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 72, No. 4, page 48).

Add comment