On a hot summer morning last August, a long line of cars waited in the Edmondson Village Shopping Center in Baltimore. The drivers, including some who arrived two hours early, were there to exchange weapons for money, no questions asked, during a gun buyback event organized by the nearby St. Joseph Monastery Parish.

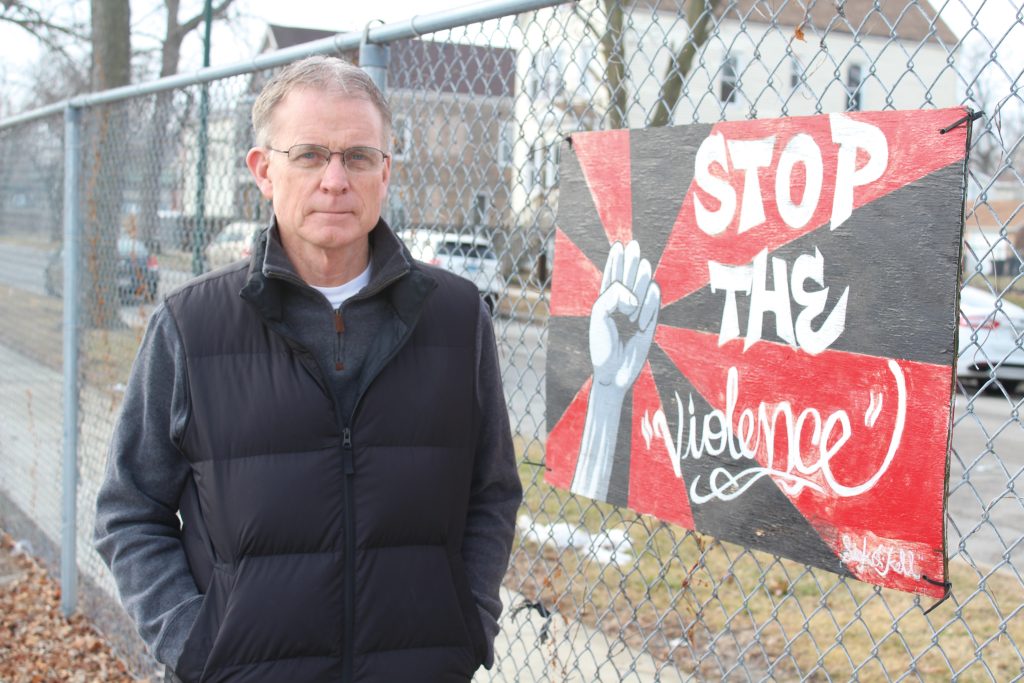

Father Mike Murphy, pastor and Baltimore native, was inspired to organize the buyback because of his city’s ongoing struggles with gun violence. From 2015 to 2022, his city surpassed a devastating 300 homicides per year. Murphy chose the shopping center location because a young man had been killed there earlier in the year while on a lunch break from his school.

“Our goal was to get weapons off the street as much as possible,” Murphy says. “Having it in a place where somebody lost his life was a way of showing, ‘We have to do better at promoting a culture of peace.’ ”

Murphy worked with diocesan partners to raise $60,000 for the event, which paid $200 to 300 per gun. By the end of the day, the team collected 362 weapons to melt down, including 17 semi-automatic weapons and three guns that had been previously reported stolen. Following the buyback, his parish helped organize a prayer vigil walk in December where parishioners read the names of those killed by gun violence in the previous year and prayed for peace. A second buyback event is scheduled for this summer.

Murphy calls the buyback event “a powerful statement” and is proud that those guns can no longer be used for suicide or domestic violence or end up in dangerous hands. He believes anti-violence efforts like this one are an important way his parish can meet communities’ needs and provide hope.

“Pope Francis is constantly calling for an end to violence and violent crime, and the church has a great opportunity to leverage and encourage peace,” he says. “As a major stakeholder in the community, our parish needs to be involved in the life and health of our city.”

Of course, gun violence is not just limited to Baltimore. According to the advocacy group Everytown for Gun Safety, an average of 43,375 people die of gun-related causes in the United States each year. Nearly 6 out of 10 gun deaths are suicides. And the U.S. gun homicide rate is 26 times higher than that of other high-income countries.

Order of St. Francis Sister Maria Orlandini lives in Washington, D.C. and works as the director of advocacy for the Franciscan Action Network, where she helps push for anti-violence legislation. Throughout her career, she has seen how deeply gun deaths can harm a community.

“Right now in D.C. and in many places around the world, we’re really experiencing what it means to be in a gun violence crisis,” she says. “This is no longer about gun prevention; it is a health crisis because of the number of people who are dying every day.”

This winter, Orlandini attended a prayer vigil for Ryan Realbuto, a 23-year-old member of the Capuchin Volunteer Corps who was shot and killed while spending a year of service in Washington, D.C. “When something like this happens, it’s not just about the person who dies,” Orlandini says. “There is Ryan and his family who are affected, but there are also the people with whom he was living, the school and the students with whom he was working, the whole neighborhood surrounding him. This is a big problem in our country—not just the number of people who die every year, but also the hundreds of thousands of people who are traumatized in their suffering and grief, who don’t know what to do next.”

Like Murphy, Orlandini is part of a growing movement within the Catholic Church that is taking action to raise awareness and reduce violence in their communities. Inspired by their faith and a collective sense of grief, these Catholics are using all their tools—advocacy, policy, prayer, and even art—to bring about a more peaceful world.

“Seeing that this issue is so big and there is so much suffering, you wonder, ‘What can I do?’ ” Orlandini says. “This is something we need to pick up as Catholics. [Gun violence] is a crime against God’s love and mercy, and it’s something we cannot ignore.”

Advocating for change

The gun violence crisis has long been a topic of discussion within the Catholic Church. In 1994, the Vatican released a document titled International Arms Trade: An Ethical Reflection, which explicitly called for strict control on the sale of handguns and small arms. Pope Francis has spoken frequently against the arms industry, including in 2022 when he reacted to the mass shooting in Uvalde, Texas by saying, “My heart is broken over the mass shooting at the elementary school in Texas. . . . It is time to say enough to the indiscriminate trafficking of arms.”

In the United States, prominent church leaders, including Cardinal Blase J. Cupich of Chicago and Cardinal Joseph W. Tobin of Newark, New Jersey have responded to mass shootings with expressions of grief and calls for stricter gun control legislation. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops has also released several statements regarding gun violence, beginning in 2000. In 2022, the conference released a letter expressing heartbreak over recent mass shootings and calling for strong congressional action, including a “total ban on assault weapons.” The letter was signed by the Conference’s four chairmen: Archbishop Paul S. Coakley of Oklahoma City, Archbishop Salvatore J. Cordileone of San Francisco, Bishop Thomas A. Daly of Spokane, Washington, and Archbishop William E. Lori of Baltimore.

“There is something deeply wrong with a culture where these acts of violence are increasingly common,” the bishops wrote. “There must be dialogue followed by concrete action to bring about a broader social renewal that addresses all aspects of the crisis. . . . Among the many steps toward addressing this endemic of violence is the passage of reasonable gun control measures.”

Although the church’s stance on gun violence is clear, Orlandini and others feel that church leadership needs to be speaking more about the issue, especially given how immense the violence rate really is. Everytown for Gun Safety reports that 120 Americans are killed by guns on a daily basis, including a disproportionate number from Black, Latino/a, and Indigenous communities. “If there is an issue that needs to be addressed more by the church, it’s this one, because children are dying and young people are dying,” she says. “We should use our influence in this case to save lives.”

Last spring, Orlandini helped to organize Nuns Against Gun Violence, an inter-congregational coalition that aims to mobilize religious sisters, associates, and their supporters against gun violence using prayer, advocacy, and education. Within its first year, the group has grown to include more than 60 congregations in all 50 states and beyond.

“In doing this, we’re trying to fill a hole in the conversation where often our voice as Catholics is not being heard,” she says. “Although we can’t change the bishops’ response, we believe we can change the Catholics in the pews around the country and get them involved and advocating for legislation.”

Angela Howard-McParland, justice resource manager for the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas and another founder of Nuns Against Gun Violence, agrees that Catholics need a stronger voice when it comes to the gun crisis. Although the church has a clear stance on gun control, she believes church leaders discuss it significantly less than other moral issues like abortion.

“I live in a very blue state, and I’ve never heard gun violence preached about in a parish,” Howard-McParland says. “Catholics in particular have a responsibility to be speaking about this as a pro-life issue and a gospel mandate.”

As part of the coalition, Orlandini and Howard-McParland work to amplify the anti-violence efforts some sisters have been doing for years while providing resources to encourage more congregations to get involved politically. As a policy expert, Howard-McParland encourages sisters to write to Congress in support of the Assault Weapons Ban, Ethan’s Law (which would regulate the storage of firearms on residential premises), and bills addressing gun trafficking within and out of the United States. During Lent this year, the coalition’s fast to end gun violence included letter templates people could print, sign, and send to Congress. And in 2023, Nuns Against Gun Violence, along with the Sisters of Mercy and other Catholic congregations, participated in an amicus brief introduced by Jewish Women International that urged the Supreme Court to keep guns out of the hands of domestic violence abusers.

Other sisters within the coalition have approached the issue through shareholder activism, using their pension money to buy stock in gun manufacturers and retail companies where they feel they can affect change.

One such coalition, comprising sisters from the Adrian Dominican Sisters of Adrian, Michigan; the Sisters of Bon Secours USA of Marriotsville, Maryland; the Sisters of St. Francis of Philadelphia of Aston, Pennsylvania; and the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary, U.S.-Ontario Province of Marylhurst, Oregon, has been participating in shareholder meetings for the firearm manufacturer Smith & Wesson since 2018. Each year, they’ve put forth proposals asking the company to take responsibility for the weapons they are manufacturing and selling. Among their requests, the sisters push for Smith & Wesson to stop marketing to children through placements in video games and other media; to change production to make it harder for weapons to be modified; and to rigidly follow guidelines about where weapons are allowed to be sold.

After years of their proposals being ignored, the sisters raised the stakes in 2023, working with lawyer Jeffrey M. Norton to sue the company’s board of directors on behalf of Smith & Wesson, with the argument that by manufacturing, marketing, and selling semi-automatic rifles, the board is putting its own company at great risk. While this kind of shareholder lawsuit is not new, Norton said it is the first time it has been attempted against a weapons manufacturer.

Howard-McParland hopes that Nuns Against Gun Violence will enable more congregations to learn from one another and keep pushing boundaries to make positive change. “There are so many justice and faith initiatives with sisters standing on street corners all around this country asking for an end to gun violence,” Howard-McParland says. “None of us are reinventing the wheel. This work by Catholic sisters has been going on for years.”

Advocating through grief

Outside of pushing for policy change, many Catholic religious center their anti-violence efforts on accompaniment and prayer. In Chicago, Sister of Mercy Joy Clough participates in a regular prayer vigil with an inter-congregational group of sisters and religious brothers. On the last Saturday of each month, her group travels to a site of a shooting and offers prayers for Chicagoans affected by gun violence and those working to promote peace.

“We start by naming out loud each person who was killed that month, the day of their death, and their age,” Clough says. During one prayer vigil last July, she says, there was at least one person named for every day of the month, ranging in age from infants to senior citizens.

“The first time I went, I was so stunned by the number of people killed in a month,” she says. “So many victims are accidental, but that doesn’t change the fact that they’re dead. Their families are ravaged and the neighborhood where it happened is traumatized.”

The group’s goal is to provide a witness of hope, healing, and comfort. As a white woman praying with a majority white group, Clough also hopes to show the predominantly Black and Latino/a neighborhoods that they are not alone in their grief. “This is a little way of showing this is everybody’s problem,” she says. “Part of our witness is that life is valuable and that people should be respected. That crosses all racial lines.”

Similarly, Sister of Mercy Natalie Rossi, of Erie, Pennsylvania, is an active participant with Take Back the Site, a ministry that holds 15-minute prayer vigils at locations where gun violence has occurred with prayers, songs, and—if possible—a few words about the deceased. Founded by the Benedictine Sisters of Erie in 1999, the ministry also involves the Sisters of Mercy and Sisters of St. Joseph.

The goal of the vigils, Rossi says, is to try to counteract the violence that occurred with a sense of peace. The sisters work with police officers and local funeral homes to contact family members of the deceased and offer comfort and support. If a family can attend the vigil, Rossi hopes it provides a sense of closure.

“At first when I approach families about doing this, they might be hesitant,” she says. “But when they come to the prayer service, they see people from Erie who they don’t even know are praying for their family. It means a lot.”

In Alton, Illinois, Catholic artist Christine Ilewski-Huelsmann uses art to honor victims and educate others about the reality of gun violence. As part of her nonprofit, Faces Not Forgotten, she and a team of volunteer artists paint realistic portraits of children and teens who have been killed by guns.

Ilewski-Huelsmann was inspired for the project after the death of her friend, Missionary Oblate of Mary Immaculate Father Larry Rosebaugh, a lifelong social justice activist who was shot during a 2009 carjacking in Guatemala. Ilewski-Huelsmann’s first portrait was of 16-year-old William Jenkins, a Chicago teen who was killed while working at a fast-food restaurant. She reached out to William’s father for permission to paint him, then gave him the original and kept a copy for her own advocacy work.

In the years since, she and hundreds of volunteer artists have painted more than 300 portraits, including 19-year-olds in their first year of college and many children and babies shot through windows by stray bullets. The original version of each portrait is provided as a gift to the families in mourning, while digital versions are superimposed over an image of a vintage handkerchief and joined together in groups of eight to form quilts representing individual cities or states.

Currently the nonprofit has more than 30 quilts, which are exhibited around the country. In 2022, they were displayed at the 10th Annual National Vigil for All Victims of Gun Violence in Washington, D.C. Just last year, they served as the backdrop for ENOUGH! Plays to End Gun Violence at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

For Ilewski-Heulsmann, working on the portraits has helped her process her grief around Rosebaugh as well as the death of her own father, who died from suicide by gunshot when she was 20 years old. She hopes that the people who view these portraits will gain awareness of the incredible tragedies caused by guns every day.

“To look into the faces of these children, you just can’t help but feel the innocence and the overwhelming loss,” she says. “What I’m trying to do is elevate individual humanity and put a face to each soul to help people understand that each portrait is a whole life lost. Who would that child have been?”

Rebuilding with relationships

In addition to honoring victims, some Catholic community leaders are working to support young people and families who have been affected by gun violence to help them make better choices. At Mercy Career and Technical High School in Philadelphia, School President Sister of Mercy Susan Walsh and her staff find themselves on the front lines of the gun crisis as they educate students experiencing violence in communities throughout the city. In recent years, three students were lost to gun deaths.

“When that occurs in a small school, a Catholic school, we really go into action for the family and the classmates,” Walsh says. “When someone is there Friday and they’re not there Monday and not coming back, it ripples through the school.”

After each death, the school has gathered in prayer to honor the person who was lost. On-staff social workers and guidance counselors work with the victims’ families to offer resources and support. The school also organizes grief support programs and workshops on peaceful conflict resolution for students and staff. “We’ve provided funds for family needs, but we’ve also rallied around each other,” Walsh says.

Because gun violence can be so common in student neighborhoods, many students stay sheltered in their homes much of the time. Faculty are encouraged to keep pushing students academically while showing sensitivity and awareness of what they might be going through outside of school walls. Walsh hopes the school can be a safe harbor where students feel free, with a variety of after-school organizations and opportunities to get involved.

“The teachers are dedicated to the fact that this school could be their happy place,” she says. “We try to be open to talking to the students and telling them that this affected us, too. By verbalizing it, that helps the students potentially talk about it and know that it’s not just them feeling that way.”

Missionaries of the Precious Blood Father David Kelly is the executive director for Precious Blood Ministry of Reconciliation in Chicago, which uses the ideas of restorative justice to offer hope and healing for individuals affected by violence or incarceration. Approaching gun violence as a public health issue, the ministry team thinks holistically about its causes and provides a wide range of financial, legal, spiritual, and relational resources to help people overcome grief and trauma, build relationships, and learn to respond differently to conflict. “So much violence happens because of poverty, trauma, and inequities,” Kelly says. “We can’t come at this with a simplistic mindset.”

The ministry team includes people who have been incarcerated themselves and welcomed back into the community. During times of violence, outreach ministers work to de-escalate crowds and keep people safe. After an event, they will reach out to everyone involved to help with next steps like applying for victim’s compensation, entering a rehabilitation program, or preparing for a funeral. They’ll offer resources for grief support, housing, or unemployment assistance, and—if a person is ready to make more major changes—they will connect them with case managers for personalized mentoring and support.

Kelly believes it is the role of the church to be out in the community helping those who need it. He knows some parishes are wary of opening up resources like gymnasiums for public use because of fear and negative stereotypes about young people from communities experiencing violence. By casting off assumptions and adopting a spirit of radical hospitality, he believes Catholics could have a real impact in creating places where marginalized young people would feel safe and supported.

“Most of the young people I deal with carry guns because they don’t feel safe in their community,” he says. “They know they are vulnerable because they’ve lost loved ones, they know the neighborhood can be dangerous especially for Black and brown people, and they know adults can’t protect them.”

For Kelly, this isn’t just about responding to violence. It’s about creating a better community. “We need to create safer spaces and that means we need to come out of our churches, our sanctuaries, and schools and engage with the community,” he says.

This article also appears in the June 2024 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 89, No. 6, pages 30-35). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Header image: Calandrian Simpson Kemp (left), mother of George Jr, and Shirley Anderson (second from right), grandmother of Carson, along with other members of COPS/Metro, a social justice organization based in Texas. Courtesy of Christine Ilewski-Huelsmann

Add comment