When Marcia Lane-McGee worked as a Catholic youth minister in Indiana, she found that one topic inevitably tripped up the young people—especially the girls—in her care: food.

The reason: They feared it would make them fat.

—Marcia Lane-McGee

Image Courtesy of Ave Maria Press.

But Lane-McGee doesn’t blame the girls. She knows the body image messages they are pelted with, even in church spaces. “It’s not just Catholics. It’s any community that associates itself with food,” she says of the presence of pizza at youth events and donuts after Mass. “You’re encouraged to eat—but not too much.”

Claire Willett, an Oregon-based playwright who has also worked in Catholic youth ministry, affirms that churches can be “really toxic places for fat bodies,” with people bringing their societal biases with them. “My body has been a real pain point sometimes in those situations,” she says. “People form their opinions of you just by looking at you.”

Catholics’ relationship with food and how it can change one’s body ties directly into central tenets of the Catholic faith. The incarnation is God taking on a human body, and in the Eucharist Jesus continues to feed his followers with his very body as they gather around a table and share a meal at every Mass.

Having an aversion to food and disparaging certain types of bodies—whether one’s own or someone else’s—often result from embracing cultural norms that have nothing to do with Catholicism. They distance believers from loving others in their suffering and ultimately detach them from what it really means to be one body in Christ.

Fatness in faith spaces

Willett finds that objections to her being fat stem from people who associate her body type with decadence, gluttony, and a lower moral standard. “That’s the body of somebody who is susceptible to sin! They can’t say no to things,” she says of the stereotypes around this.

Willett also faces assumptions about her life from other Catholics because she is queer. “It is impossible to escape people making judgments about the kind of person you are,” she says. “Jesus wouldn’t have done that. . . . The most significant stories about who Jesus was are very explicitly about looking past the one thing everybody else can see about you and [instead] seeing the person and what the person has to offer.”

Lane-McGee agrees that people make assumptions about her based on her size and race all the time.

“I am the overbearing, sassy Black woman, and my physicality kind of leans into that,” she says. “You can see that I’m larger than this person or that person, but it shouldn’t matter. . . . All bodies are beautiful.”

“There’s not really the option to be cruel to your body, because the body has forever been elevated to something different from everything else in the world because of the incarnation,” says Catholic author Simcha Fisher. “Christ took on a human body. That’s why you can’t dismiss the notion of being compassionate to the human body.”

“There’s no immediate encounter with the world. It’s always with our bodies,” says Amanda Osheim, associate professor of practical theology at Loras College in Dubuque, Iowa. “Our brokenness is experienced in physical ways.” Osheim finds this reality especially pressing after communion, praying among her fellow Catholics who have also been transformed into the body of Christ through the Eucharist.

—Amanda Osheim

“What does it mean to yourself to start being one with them? And isn’t that a challenge sometimes?” she asks. In how the church presents something like a fat body, she notes the message can be anything but welcoming. “There’s the prophetic spiritual warning not to become that.”

Emily Kahm, assistant professor of theology at the College of St. Mary in Omaha, concurs that the idea that fat bodies are good is “so hard for people to conceptualize.”

Kahm, a tall, plus-size woman who had a baby last year, finds that the people who seem to be most unaccepting of other people’s bodies are usually the ones who have the biggest issues with their own, even if they are thin. But, she says, “That doesn’t change the pain they can cause.”

“Your superiority to that other body is part of how you see yourself,” Willett says. “If you’re a thin person and sincerely believe that the way you eat and the way your body looks are signs of your virtue, and that fat people are therefore inherently less virtuous, then [that’s] a big part of your identity.”

Good bodies, bad theology

The association of thinness with goodness runs deep in U.S. culture, especially U.S. Christian culture, which finds its roots not in Catholic theology but in Calvinism. The Calvinist belief in predestination led to the widespread perception that material success in this life reflected who was blessed by God and who would be saved. Its contemporary iteration, especially in the United States, is often called the prosperity gospel. “Diet culture as it relates to the church is like another form of the prosperity gospel,” Lane-McGee says. “Church groups have weight loss groups. I am not a fan of diet culture.”

“So much of American thinness and diet culture and weight loss culture and the way we fetishize certain bodies and certain kinds of behaviors is very Puritan,” says Willett.

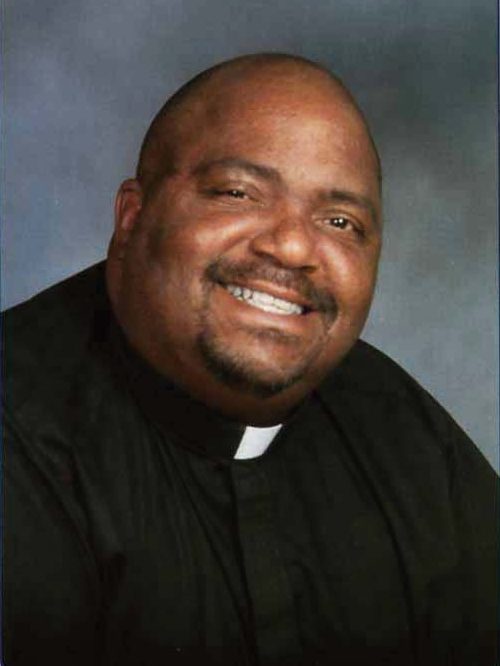

“I see the church as being much more both/and in our theology,” says Father Bruce Wilkinson, a retired priest of the Archdiocese of Atlanta. “But the way we live it . . . embracing the Protestant work ethic, is to say, ‘If you’re not doing well, then that’s your fault.’ ”

—Claire Willett

Lent is one area of Catholic faith practice that is especially beset by diet culture and prosperity gospel mindsets. Osheim stresses that the purpose of going without is “so that I can be in greater solidarity with those who always go without. How is my asceticism greater solidarity and not my Lenten weight loss program?” However, she admits, “That’s a difficult message to get across, especially in a culture that has so many conflicting messages about our bodies.”

“A lot of people make Lent a diet plan, and . . . that’s not great,” says Lane-McGee. “This is disordered eating, and I think people don’t realize that.”

Marginalized bodies

Conversely, consuming the Eucharist while not striving to be in actual solidarity with those in need could also be termed a form of disordered eating.

“We are called to the trenches, the margins. That is precisely our faith,” says Amanda Martinez Beck, cohost of the Fat & Faithful podcast and author of the book More of You: The Fat Girl’s Field Guide to the Modern World (Broadleaf Books). A former evangelical Christian and convert to Catholicism, she adds, “I was drawn to the Catholic Church out of a hunger for the Eucharist and its teaching about bodies, which are immigrant bodies, which are gay bodies.”

In the United States this could also take the form of solidarity with the Black community, whose poverty rate is higher than any other race/ethnicity and of whom over a third of adult men and over half of adult women are classified as obese. Behind these numbers is the widespread reality of food deserts: Many low-income areas are without access to a supermarket.

“People have to drive miles, literally many miles, to get to a grocery store. And even then, when you get to that grocery store, the quality of that food might not be the same as it is in other areas,” says Wilkinson, who is Black. “We have plenty of . . . fried chicken franchises and McDonald’s.”

“It’s a lot more than just ‘I don’t have money to buy food today.’ It’s also ‘I don’t have a way to get to the grocery store’ ” and other factors including child care, work schedules, and the need to sleep, says Kahm. “There are extra barriers between you and eating the meal that you want to eat.” Ultimately, she adds, “You’re gonna walk to McDonald’s. You have $3. You can get a full meal for that.”

Of course, fast foods and processed foods, such as those found at convenience stores, have more salt and more calories and make people who eat them more likely to gain weight or be at risk for diabetes. This, notes Kahm, is systemic racism at work.

“We have created a system by which those non-idealized bodies are going to become non-idealized in more ways,” she says.

—Amanda Martinez Beck

Through this lens, Lenten solidarity with those in need might more accurately resemble 40 days of eating processed and fast foods—as someone in a low-income area likely would. But just as white Catholics in a suburban parish would probably avoid a Lenten program that would almost assuredly make them gain weight, they are also generally uncomfortable with the idea that Jesus could have resembled something other than the sculpted white body hanging above their altar.

In late 2021 two different copies of a painting depicting the pietà (Mary holding the dead body of Jesus), with Jesus strongly resembling George Floyd, were stolen from the walls of the law school of The Catholic University of America. For Catholic author and University of California–Berkeley writing faculty member Kaya Oakes, the episode raises a central question.

“Why can’t we see Jesus in that body?” she asks. After all, Jesus was a man of color who died an unjust, shameful, and public death at the hands of the state. But rather than citing this connection, Oakes cites the attitude of commentators who said that Floyd would have died anyway because of his weight, an example that manages to blend racism, fatphobia, and ableism.

“Do we have the capacity to imagine [Jesus] in an imperfect body? Because he was human,” Oakes asks.

Kahm says that when she sees a crucified Jesus with six-pack abs, her reaction is, “Really? He was in his 30s, and that takes really specific work.” She adds, “Nothing about our history tells us Jesus had a perfect body. There’s no reason to think he did. We’ve just gotten lazy with our imagery.”

She says that, for all the artistic depictions of Jesus—as a refugee, as a woman—fat Jesus is a bridge too far for people. “In our cultural milieu, to be fat is to be a joke. To be fat is to be associated with sins.”

Examining our layers

Despite bodies being forever glorified as a result of the incarnation, Kahm notes that most Catholics—and people in general—haven’t made peace with embodiment. “We really are profoundly squeamish around bodies being anything but what we dictate them to be,” she says. “Bodies are a mixture of things we don’t control and things we do.”

Women go into labor. People live with anxiety and depression for decades. “We don’t want to let go of this idea that we’re self-made, that we can be whatever we want,” says Kahm.

Fat and other marginalized bodies also remind people of their privilege in ways that can be uncomfortable, Osheim says, and, in order to grow in their love and sense of belonging, Catholics need to examine the complicated layers of privilege that every person brings to the table. She cites her own identity as an educated, middle-class person as among the “many forms of social privilege” she carries into the church.

—Father Bruce Wilkinson

“It does require a level of personal and communal discernment to work through those,” she says, and the process raises questions of “What does that mean for how we go out and accompany others who we meet along the way?”

Osheim adds, “This is something we learn and are going to need to keep learning.” It is a component of synodality, the model of church as walking together and listening to one another, that Pope Francis espouses.

This might include rethinking fatness within a framework that’s actually Catholic. Martinez Beck suggests adopting the lens of God’s abundance and gratuitous giving: “Think about a steak that has no fat on it. And then think about a steak that’s marbled and how beautiful the flavor is of one,” she says. “Fat brings flavor. Fatness is beautiful. . . . Fat is a protective preservative. Think about babies who are fat. Think about how we love it when they’re chunky.”

And even if many people can’t bring themselves to the point of celebratory embrace, Fisher, who has birthed 10 babies and written about her own struggles with weight through the years, offers an alternative: “Gentle sympathy for our bodies is something I’m trying to achieve,” she says.

Toward physical action

When it comes to the challenge to love one’s neighbor as oneself, Wilkinson has noticed a recent trend in U.S. Catholicism to separate the spiritual from the physical, exemplified by practices such as eucharistic adoration, which people can sometimes be drawn to “because it demands nothing of you physically,” he says. “Worship is an act of prayer and of physical response. . . . Christianity is all about being uncomfortable.”

“We have to figure out a way to bring the body and the spirit back together,” Oakes says. “I think that begins with conversations about our prejudices about what kind of bodies are good and what kind are bad. And that’s a perfect conversation for Catholics to be having.”

For achieving such a communal conversation, Wilkinson lifts up the example of the large family gathered for dinner—loud, chaotic, sometimes arguing, often laughing, and sharing stories. “It leads to the dialogue and the understanding of what we do at the table,” he says. By contrast, he notes that a culture defined by the rugged individual—whether feeling isolated in their spiritual practice or getting fast food alone after their shift—doesn’t have this dialogue.

Not only does dialogue at table help people learn and grow, it also echoes the pervasive church concept of feasting and goes right back to the example of Jesus: “Jesus spent a whole lot of time telling stories. He talked a lot before they ate,” says Wilkinson.

Willett recalls her mom’s large, Catholic, Polish, and Austrian family who could always be counted on to feed guests with a shared meal. “It’s something I deeply associate with how we show people that we love them,” she says. Willett feels that breaking bread together is “very connected” to manifesting the relationships of life. “Finding a way to allow in our human bodies and in our relationships the communal experience of sharing food, like real human food, to nourish us in the same way that the Eucharist does spiritually, that feels very Catholic.”

“Every person, no matter their size, struggles with their body,” Lane-McGee says. “It’s universal. It is super Catholic to embrace that.”

And in that shared struggle with the vulnerability of embodiment, perhaps a new sense of belonging can take hold. Or as Lane-McGee puts it: “Even the big bodies can be the body of Christ.”

This article also appears in the July 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 7, pages 16-20). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/canweallgo

Add comment