The high walls of writer Andriana Trigiani’s Greenwich Village home are lined with books of all shapes, sizes, and titles. It’s like a small-town library, but without the rectangular reading tables, or the archetypal librarian signaling patrons to keep their voices down. This library-like setting is Trigiani’s way of paying homage to the librarians and teachers who encouraged her love of reading and writing over the years. Almost every one of her 19 novels contains some reference to librarians, religious sisters, or classroom teachers and the important work they do, especially in small, rural communities.

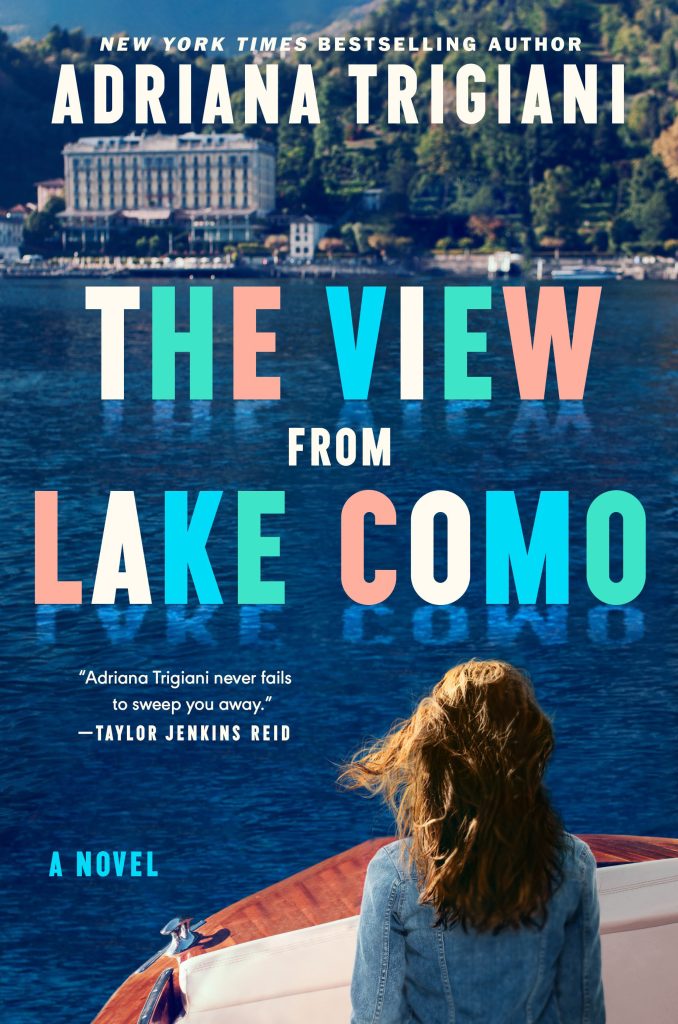

Another recurring theme in Trigiani’s work is the struggle of newcomers and outsiders to find their place in new environments. Her newest book, The View from Lake Como (Dutton)touches on this theme and, like much of her work, bears the imprint of her Catholic faith.

The View from Lake Como is a poignant portrait of the strengths, weaknesses, contradictions, and durability of Italian-American families. As such, it is a tribute to the many Italian forebears who arrived in North America over the last several generations to build new lives for themselves and their progeny.

The novel tells the tale of the Capodimonte and Baratta families, who struggle to maintain a marble supply company in Monmouth County, New Jersey. The title has a dual significance: The “view” is from both Lake Como, New Jersey and the more renowned Lake Como region in Italy, long known for the high-quality marble in its many quarries.

As with many of Trigiani’s stories, The View from Lake Como is told from the perspective of a middle-aged woman who, despite the constraints placed on her because of her gender, finds contentment in life and work. In this story, the protagonist’s path to fulfilment involves taking over a beloved uncle’s marble supply and design company.

“The Lake Como book is about a woman who has to be rebuild her life,” Trigiani says. “She announces it, sticks with it, and eventually succeeds in the rebuilding through her work as a draftsman in the New Jersey marble company.”

Some of Trigiani’s narrative in The View from Lake Como touches on another of her common themes: that of immigrants, whether first or second generation, finding their place in a new land. Although many of Trigiani’s protagonists struggle with the sense of being an outsider, they eventually find acceptance in their new home countries without having to surrender their culture and cherished traditions.

This theme emerges in Trigiani’s 2018 novel, Tony’s Wife (Harper Collins), the tale of a mid-20th century New York area Italian family’s ups and downs as nightclub singers and song writers. In one scene, a character muses on popular music as an expression of the spirit of the times: “Something is [his] bones told him that a song with humor in the midst of Great Depression would be a balm, and if that song was also personal and specific to the immigrant experience—in this case Italian, but surely the Jewish, Polish, Greek, or Irish who populated the shore towns and cities a train ride away could relate to it, too, as long as the song’s sentiment was true to their particular culture’s traditional view, that tune would hit.”

Characters in Trigiani’s novels find beauty and meaning in various forms of creativity, as well as in their sense of familial identity. Often, the Catholic faith is central to their lives and their personal growth, as they struggle with challenges and setbacks.

Trigiani was born in Pennsylvania but grew up in Big Stone Gap, Virginia, in the southwest corner in Appalachia country. She later attended St. Mary’s College in South Bend, Indiana, in the shadow of the majestic University of Notre Dame. As an undergraduate at St. Mary’s, Trigiani studied with the Sisters of the Holy Cross, who furthered her appreciation for art, beauty, and creative storytelling. While at the college, Trigiani wrote and directed a play performed on the college’s mainstage. Even then, critics and colleagues took note of her emerging talent and creativity. Although Trigiani is best known today for her novels, she is also an accomplished filmmaker, director, and producer. In the late 1980s, she moved to Greenwich Village to pursue a career in film, television, and fiction writing. Her first novel, Big Stone Gap (Random House), was made into a film of the same name, with Trigiani serving as director.

Her novel The Good Left Undone (Dutton) came out in 2022. In the “Acknowledgements” section, Trigiani said the book “is about how we live and what we leave behind after we go.” This novel tells the story of Domenica, a nurse and hospice worker who, prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, is forced from her native Tuscany because she showed too much sympathy to young women looking to avoid unwanted pregnancy. During her travels, she experiences some of the little-remembered antipathy toward Italian immigrants in the Second World War years.

Although this story touches on the anxiety and oppression outsiders experience, it also highlights hope amidst trying times. As a Catholic chaplain reminds a boatload of exiles facing deportation, “[God] will not forsake you. He will not abandon you. But you must pray. God knows your heart.”

In her 2010 memoire, Don’t Sing at the Table (Harper), Trigiani expanded on her use of family history and her grandmothers’ habit of spinning compelling stories as material for future novels: “Family was presented to me as a landscape loaded with characters whose lives had surprising twists and turns and who grew and changed as the stories of their lives played out. With my imagination populated by these fascinating characters and the things that happened to them, all it took was some education and discipline to find my craft.”

In the same book, Trigiani elaborated on the strong bonds between Italian culture and the Catholic faith. Being Catholic, she writes, “is as much about being Italian as it is about religion.” At the same time, she wanted to decide who she would be for herself. “I wasn’t sure who I was in the eyes of religion,” she writes, “but I always knew who I was in the eyes of God. I didn’t like to be in the position of defending my church. This was something I was born into, not something I had chosen for myself.”

Given her love of libraries and reading, it was only natural for Trigiani to help others better access literary resources. After the release of her debut novel Big Stone Gap, Trigiani cofounded a reading and writing program for young people in wider Appalachia region. Known as the Origin Project, the program includes passing out journals for students from kindergarten to 12th grade for the purpose of doing their own writing. On occasion, established writers such as Lisa Scottoline and David Baldacci visit the students and offer insights on how to find their writing voice.

The stories compiled by Origin Project students preserve, in a small but meaningful way, the lived experience of this diverse group of budding authors. As Trigiani noted in a recent post on her Substack, “Appalachia is the heart of American literature, music, and art. It is there, in Big Stone Gap, that we began with 40 students in one school. Twelve years later, we have served nearly 50,000 students, grades K through 12. If it seems like a miracle, it is.”

The project’s success is especially gratifying to Trigiani for its power to draw young writers of all backgrounds into a creative community. “The students matter because their stories matter,” Trigiana says. “This corner of the American quilt is patchwork beautiful. The students are Scots-Irish, African-American, Middle Eastern, and more. They are immigrants. They are children of immigrants. They are children whose ancestors date back to the American Revolution. They are all these things and more. Their unique voices of inclusion, celebration, and camaraderie will thrill you. But you don’t have to believe me—all you need to do is read their work.

When not working on a new book or film project, Trigiani serves on the New York State Council for the Arts which provides grants and financial support to up and coming artists from all media. She also maintains a blog, suitably titled You Are What You Read, which encapsulates the author’s understanding of reading, literary, and creativity in the development of young minds.

Trigiani remains firmly committed to the power of art to rise above strictly earthly concerns.

“I learned to pray as a Catholic girl,” she says. “The mysticism, the prayers, and the rosary in particular matter to me. The greater goal of serving others is never far from my mind, though I come up short often and plenty. But I know how to pray, and I can thank my religion for that.”

Unsurprisingly, the significance of the Eucharist serves as a touchstone for Trigiani’s inspiration. What she tries to dramatize in her books she says, is “the breaking of the bread. That is what fascinates me as a writer.”

Image: Credit Tim Stephenson

Add comment