Years ago, I noticed an unexpected phenomenon. I had recently moved to New York, and on my afternoon rush hour commute I saw people eating as they rode in the subway. This wasn’t an instance of children eating prepackaged snacks to hold them over until dinner. Nor were these commuters simply munching on vending machine fare, anticipating a late meal out. Instead, this was their dinner. Here were people sitting by themselves on the train eating their entire dinner out of a take-out container on their lap, whether out of necessity or habit.

As one might expect in a large metropolis like New York, the food ranged from fast-food staples to take-out cuisine from diverse cultures. These diners made no eye contact with their fellow passengers, often sat in silence, and shifted in their seats as the cars began to fill. When I shared this observation with a Benedictine abbot I knew, he became pensive and offered an interesting theological insight. He wondered how people would learn the communal meal-sharing dimension of Eucharist when their experience of eating is not relational. That observation has stayed with me. If Eucharist does not readily speak of the multifaceted relationships we have—with God, with creation, with one another, with everyone involved in bringing food to the table—then there is a significant problem!

Today, our experience of Eucharist and meal sharing has become more complex. During the pandemic our already tenuous connection to natural food production often became even more distant as online ordering, curbside pickup, and delivery options removed us from even entering a grocery store. The closure of restaurants and their slow reopening have lessened the frequency of our meal sharing with a wider community. And the closure of churches to public worship, substituting live-streamed Masses with so-called “spiritual communion,” has further diminished what little sense of the “breaking of the bread” the Mass conveyed in our contemporary liturgies. Each of these has further alienated us from God, one another, and creation.

Many of these precautions were taken out of sincere care for the common good, but there were unforeseen consequences. After centuries of Christian worship where bread slowly became industrially mass-produced wafers and the Lord’s Supper slowly became individualistic religious ritual and rubric, it’s difficult after the height of the pandemic to even get people to return to Mass, let alone make significant connections between Eucharist, food, meal sharing, and relationships. Many parishes have now become mini broadcast booths where parishioners tune in to watch Mass at their convenience, often tuning out after the homily. The U.S. bishops are aware of the seriousness of this challenge and have begun a three-year plan to focus on Eucharist, which the Second Vatican Council called the “source and summit” of our faith.

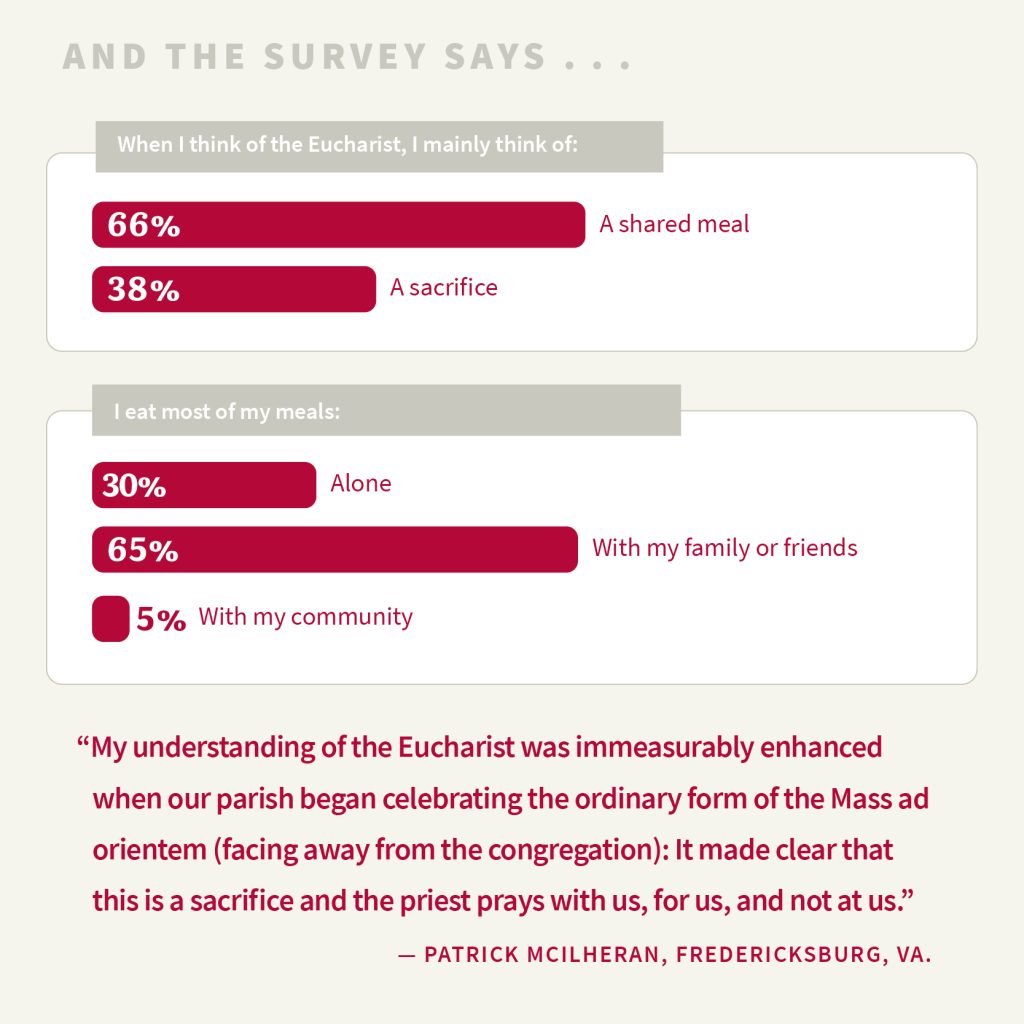

This is important, but the solution cannot be “more catechesis,” scholastic definitions of the real presence, or eucharistic devotions that make Eucharist more of an object than a sharing in the life of Christ. So much of our eucharistic theology and practice forgets or avoids what many biblical scholars identify as Jesus’ meal ministry. Instead, the sacrificial dimension of Eucharist is what often overshadows all else. We tend to downplay the reality that we are recalling Jesus’ words and actions at the Last Supper—a meal. How often do we hear Jesus’ instruction to “take and eat” and “take and drink” as a sharing of food and offering of relationship?

At what meal in the Christian scriptures does Jesus eat alone, refuse to share, or not offer the opportunity of relationship through word and food? When we include all of Jesus’ meal sharing in scripture, we gain a much fuller sense of what Jesus is teaching us about Eucharist. Eucharist is tied to our labors and connected to the Earth, as Jesus calls Peter to bring some fish he caught to the shore in their post-resurrection meal of reconciliation. Eucharist is the offer of new life, as Jesus eats with tax collectors and sinners. Eucharist is the revelation of God’s presence with us, as Christ is made known to the disciples on the road to Emmaus, precisely in the context of a meal, the breaking and sharing of bread.

So how do we even attempt to convey all of this in our celebration of the Eucharist? How do we give a true glimpse of the in-breaking of the kingdom of God in our eucharistic celebrations? Let me suggest this: It’s not by creating distance but by offering relationship, not by emphasizing “otherness” but by recognizing nearness, and not by proclaiming from a place of power but by uttering from a place of vulnerability.

How do we do this? The path begins by making a deep and profound connection between Eucharist and meal sharing. This entails a complete acknowledgment and integration of the relational quality of Eucharist in the entire process of bringing food to the table and breaking bread. This starts with the local community growing the wheat and grapes and continues as the faithful knead and bake the bread, crush and make the wine. Each activity is accompanied by prayer and accomplished with sustainable practices, maintaining a holy relationship with God and creation. This “fruit of the Earth and work of human hands” is then brought to the altar where it will be blessed, broken, and shared.

Some may think this is idealistic or even elitist, citing unreasonable expense or excessive time commitments. Are we to believe that modern, industrially mass-produced wafers, delivered in the mail and held in plastic bags on a shelf, are ideal or give us a more accurate foretaste of the eschatological banquet? Or is this convenience more akin to fast food, springing from a fast-food mentality?

Instead, the parish community could renew its eucharistic life by evaluating each step in the process of bringing food to its altar, looking for opportunities to acknowledge sacred relationships and Catholic values throughout. Theologian Mary E. McGann offers numerous ways to approach this situation anew in her insightful and well-researched book The Meal That Reconnects: Eucharistic Eating and the Global Food Crisis (Liturgical Press). Here she deftly identifies the short- and long-term harm the industrial global food market has upon the Earth and its most vulnerable populations. Aligned with Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical Laudato Si’ (On Care for Our Common Home), she highlights the many “relationships” that industrial food production harms. She offers guidelines for local communities to meaningfully connect Eucharist with sustainable food production, service to the poor and marginalized, and significant liturgical meal sharing.

McGann and others don’t propose one-size-fits-all answers. One parish may begin a baking ministry to supply bread for its eucharistic celebrations. Another may partner with a local farmer in the intentional growing of wheat for Eucharist. Yet another may introduce communal meal-sharing opportunities that speak to its mission and values, while giving parishioners an experience of sharing a meal more like Jesus’ meal ministry. Importantly, it would be the local parish community that actively engages in discovering and sharing the manifest ways Eucharist builds, acknowledges, and sustains relationships.

Jesus uses meal sharing to convey to his contemporaries what the kingdom of God means. Can we use meal sharing to rediscover not only the heart of the Eucharist but also our eucharistic calling?

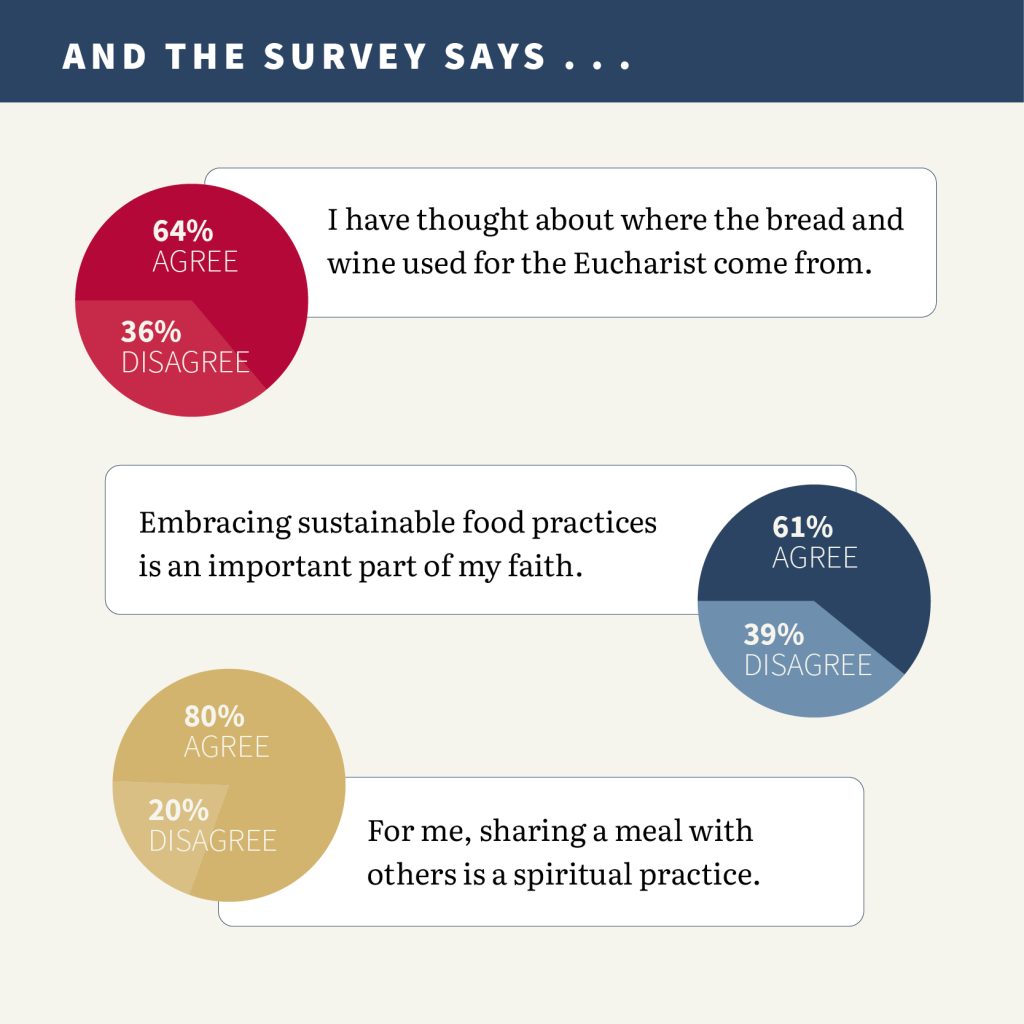

Results are based on survey responses from 152 USCatholic.org visitors.

Sounding Board is one person’s take on a many-sided subject and does not necessarily reflect the opinions of U.S. Catholic, its editors, or the Claretians.

This article also appears in the July 2022 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 87, No. 7, pages 25-29). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Pexels/Roman Odintsov

Add comment