I hadn’t heard of the Claretians or their founder, St. Anthony Mary Claret, until a priest gave a talk about them to us eighth graders at St. Mel Grammar School. When I entered the Claretian junior seminary, though, I read all about Claret, born December 23, 1807 in northeast Spain. We were encouraged to become just like him, but it wasn’t going to be easy.

The books available to us depicted a wondrous man who at the age of 5 years was thinking seriously about eternity. He didn’t have to worry about the usual temptations as much as the rest of us because the Virgin Mary had taken a special liking to him.

And no wonder—while running his father’s textile factory as a young man, he gathered the workers together to pray the rosary. That’s the kind of thing saints did.

In one story, Claret, then an itinerant preacher, was summoned to the bed of a “dying” man who was really waiting to stab Claret to death. Imagine the surprise of the schemer’s friend when Claret came back downstairs, told him that the would-be assassin had already died, and offered his condolences. The conspirator fell at Claret’s feet and immediately repented of his sins. Such was the power of the man we were taught to emulate.

When in the Claretian major seminary, I was showing a visitor the crypt of our chapel. We came upon a portrait of Claret, and I began to make excuses that the picture did not do him justice. The visitor wryly remarked, “Well, maybe he was ugly.”

At first I was shocked that anyone could call a saint ugly. It was that day, however, that I began to see saints, and particularly Claret, as possibly flawed human beings. It’s just that during their lives, saints saw the purpose of life more clearly than most of us do, and they were willing to do things to make the world a better place. We can’t duplicate all their legendary feats, but we can follow their example in ordinary things.

This realization helped me understand my order’s founder better. Claret may have reflected on eternity at age 5, but he also fought his vanity, worked hard, and struggled with his vocation.

Claret started what might have been a successful career in the textile industry, but the workaholic grew dissatisfied with his lifestyle. Rather than become anxious or depressed, he did some soul searching. He considered becoming a Carthusian hermit. Instead, he entered the Jesuit novitiate but was forced to leave for health reasons.

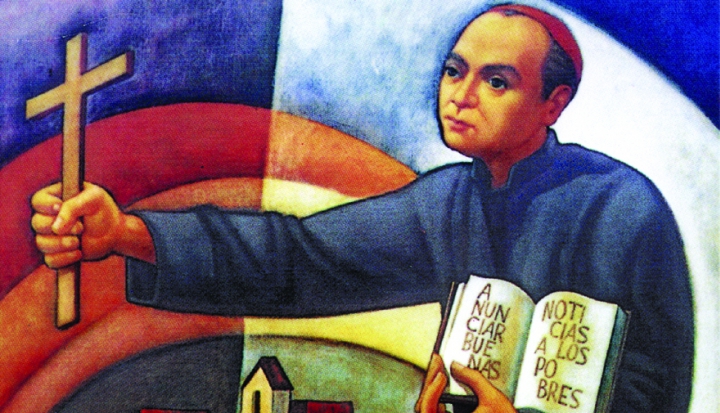

Determined to find the path God wanted him to travel, he finally was ordained a priest. He became a great preacher, founded the Missionary Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, now knowns as the Claretians, and was named archbishop of Cuba.

Claret’s vocational struggle resonated with me. For me the seminary was a constant effort—not because of the studies but because of the rigidity of the system. The superiors seemed to have a way of demeaning a person and suppressing qualities that common sense dictates are good, such as initiative and independence.

I had just about changed my mind about becoming a Claretian but then found myself praying to Claret. He did not just float through the seminary either, so I felt he would understand.

I was particularly attracted to Claret’s deep concern for people and their needs. Claret threw himself wholeheartedly into advocacy for the poor and the disenfranchised in an effort to attain social justice for them.

As archbishop of Cuba, when he saw workers being deprived of their wages by deceitful employers and working conditions that led to a dead end, he established credit unions. He fostered family life by helping change laws and customs that prevented mixed-race marriages.

That spirit seemed to rub off on us seminarians. We became supporters of the underdog, concerned about the poor, and sympathized with immigrants and migrant workers.

After struggling through seminary, I later found myself in a position to promote justice and peace through the Claretians’ investments as the provincial treasurer. I also saw to it that funds raised by the Claretians were directed to the very poor in mission areas. Now, in my pastoral work, I find myself doing all I can to aid the many immigrants in our parish.

I realized that I can do much more through my Claretian vocation than I could as an individual.

Anthony Claret, far from the portrait presented in romantic biographies, lived among real people who saw him as very much like themselves, with deep human longings and emotions.

He is a saint. He undoubtedly worked miracles. But he has shown me that sainthood is not ethereal. It is the result of facing very real problems—both your own struggles and society’s ills—head-on and looking for solutions that make life more wholesome, more peaceful, and more secure.

This article is also available to read in Spanish.

This article appeared in the December 2008 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 73, No. 12, pages 47-48).

Image: Cerezo Barredo, C.M.F.

Add comment