The history of Muslim-Catholic relations is one of both confrontation and dialogue.

U.S. President Calvin Coolidge once said, "Little progress can be made by merely attempting to repress what is evil; our great hope lies in developing what is good." As creatures of the modern age, most of us take great consolation in the idea that, however dismal the contemporary scene may appear to be, we are constantly improving on the track record of our ancestors.

Perhaps this is true when it comes to matters of technology. When it comes to matters of morality and human relations, however, "progress," as Coolidge defines it, may well be far more elusive than we would like to think.

From a modern Catholic perspective, it is tempting to think of the history of Christian-Muslim relations as one that, at least in recent decades, has been gradually moving from a pattern of confrontation and conflict to one of dialogue and cooperation. After all, with the Second Vatican Council's 1965 declaration Nostra Aetate, the church called for a new era of dialogue in its relationship with "non-Christian religions."

But in truth the history of Christian-Muslim relations, from its very beginnings until today, has simultaneously unfolded and continues to unfold along both of these major story lines-confrontation and conflict as well as dialogue and cooperation-sometimes running parallel and often intersecting.

Early clashes

The story of confrontation and conflict roughly begins with the period of early Muslim expansionism (c. 632-750 C.E.), during which Muslim armies from the Arabian Peninsula gradually advanced westward into North Africa and southern Spain; northward into Palestine, Syria, and Mesopotamia; and eastward into the Iranian plateau. No wars of conquest are without bloodshed and oppression, and neither was the Islamic political expansion in this period.

Still, the mass conversion to Islam in these regions was not "by the sword." It took place over nearly three centuries and involved, among other things, the fact that sharing the religion of Muslim rulers had its advantages.

As for the violence, Arab Muslim forces did not establish their control of this great swath of the known world through mass butchery. The Muslim conquests of the great cultural and urban centers of Byzantine Christendom, such as Jerusalem and Damascus, took place largely by armies meeting and fighting outside the city precincts, and by the victors negotiating a truce with the vanquished that protected the lives and property of the latter on the condition that they accept the legitimacy of their new overlords.

Among Christians, the socio-political reaction to the early Muslim conquests was varied. For many Christian communities, being relegated to the second-class status of ahl al-dhimma, or "protected peoples", under Muslim rule was a decidedly unfortunate turn of events, involving the loss of many rights and privileges they had taken for granted under Byzantine Christian rule.

There were other Christian communities, however, that viewed the Arab Muslim forces as liberators. Assyrian Nestorian and Egyptian Monophysite communities, for example, were deemed "heterodox" by the church of Constantinople and were therefore subject to persecution. These churches appeared to enjoy more freedom and autonomy under Arab Muslim rule than they had under the rule of their Christian brethren.

Heretics and infidels

Christian theological reaction to the coming of Islam seems to have been generally negative. From the perspective of certain eighth-century Christian theologians, Islam was not just another religion among the many others that had come and gone. It had all the markings of a Christian "heresy."

These Christian thinkers knew enough about Islam to know that it affirmed the veracity of the biblical prophetic heritage, recognizing Moses as the authentic bearer of the divine Torah and Jesus as a virgin-born messenger of the one true God, who preached the Good News and performed miracles. They also knew that Islam denied the most central doctrines of the Christian faith: the Incarnation and the Crucifixion and Resurrection.

St. John of Damascus (d. 749), who, living within Muslim domains, had the freedom to write against the heresies of Byzantine iconoclasm, which at the time was the official policy of the patriarchate in Constantinople, also apparently had the freedom to write against Islam. He deemed Islam the 101st Christian heresy and characterized the entire Islamic movement as the diabolical "forerunner of the Antichrist."

There can be no doubt that any community or tradition that seeks to define itself according to a set of normative beliefs, values, and practices needs a way to determine what lies within its norms and what does not. In this sense, the language of "heresy" has had a legitimate role to play in the history of both Christianity and Islam, each of which has seen the other as having strayed significantly from the truth.

Analogous to classical Christian condemnations of Islam as "heretical" and "diabolic" are classical Islamic interpretations of Christianity as a "corrupted" version of the original message of Jesus, who preached islam or "submission" to the one God and who never claimed divinity for himself.

But there is an apparently irresistible tendency to use concepts such as "heresy" to brand challenges to one's religious worldview as an intolerable form of otherness. Rather than simply being used to set legitimate limits on what a tradition deems to be the truth, the language of heresy has, with rare exception, been used to interpret difference as "deviation," and thus to demonize and treat as subhuman those who differ from the norm.

Unfortunately there is no more glaring example of this application of the language of heresy on the Christian side than in the theology of the Crusades (1096-1271). On one level, the Crusades were part of a longstanding Christian response to Muslim expansionism, which, it turns out, would not rest until it had taken Constantinople itself-the heart of Eastern Christendom-for Islam. It was the Byzantine loss of so much of the Eastern Christian heartland of Anatolia to the Seljuk Turks in 1071 that prompted Emperor Alexius I to seek help in his fight against the Turks from his estranged Christian brother in the West, Pope Urban II.

On another level, however, in his monumental preaching of the First Crusade, Urban went far beyond the parameters of traditional Christian "just war" discourse. His words were as controversial in his own day as they are completely rejected by contemporary Catholic teaching. Urban argued that war against the Muslims was not only "just" but "holy" as well.

From the time of St. Augustine onward, Christian theology recognized warfare as an evil that, at certain times and under certain conditions, could become a moral necessity to stop a greater evil. Urban radically augmented this line of theological reasoning by claiming that, in the case of fighting the Muslim "infidel," warfare could actually be a sanctifying and redemptive penance for the Christian warrior. There was a direct causal connection between Urban's theology and the wholesale massacre of between 40,000 and 70,000 Jerusalemites-Jews, Christians, and Muslims; men, women, and children-by the European Crusaders in 1099.

In preaching the Second Crusade, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, the great Cistercian mystic, abbot, and Doctor of the Church, took Urban's controversial theology yet another step further and argued that killing Muslims fell under the category of "malicide" (the killing of evil) rather than "homicide."

Although there are few Christian theologians today who would not be horrified by Bernard's contention, some still insist on branding Islam as an intolerable form of religious otherness. In November 2001 the Rev. Franklin Graham declared Islam to be an "evil" and "wicked" religion. In June 2002 the Rev. Jerry Vines described the Prophet Muhammad as a "demon-possessed pedophile."

Add the reality of this rhetoric to the severe political and social conflicts involving Christians and Muslims in many different parts of the world, and we can see that the history of Christian-Muslim relations is still comprised of significant confrontation and conflict. Although the roots of these conflicts have more to do with questions of nationalism, economics, the colonial legacy, and current policies of Western powers than they do with matters of religion, the dynamic of confrontation and conflict between Christians and Muslims has continued and in many ways has taken on new life in the modern period.

Spiritual bonds

Throughout all this history of antagonism and strife there is another story to tell-a story of Muslims and Christians recognizing "the spiritual bonds that unite us." The late Pope John Paul II used this expression in a homily he gave in Ankara, Turkey in 1979 at the beginning of his pontificate. In doing so he was deliberately echoing the words of his 11th-century predecessor, Pope St. Gregory VII. According to tradition, Gregory corresponded with Sultan al-Nasir of Bejaya (modern-day Algiers) and in one of his letters expressly referred to the spiritual commonalities that exist between Christians and Muslims.

From the Muslim perspective, the story of Christian-Muslim dialogue and cooperation stretches all the way back to the life of the Prophet Muhammad himself. According to this story, Muhammad was concerned with the welfare of early converts in the city of Mecca. In an effort to save them from persecution, he instructed them to emigrate to Abyssinia, where he said a just and wise Christian king, al-Najashi, would offer them asylum.

The Muslim migrants were pursued by an emissary of the pagan Meccan oligarchy. In a dramatic scene in the court of al-Najashi, the king was ready to release the Muslims to the emissary's custody when the leader of the Muslims spoke out and recited a passage from the Qur'an that recounts the Angel Gabriel's Annunciation of the birth of Christ to the Virgin Mary. Upon hearing this, al-Najashi became convinced of a sublime spiritual kinship between Muslims and Christians and refused to hand the Muslims over to their would-be persecutors.

In a later episode from the life of Muhammad, the Prophet was visited in Medina by a delegation of Christians and invited them to pray, in their own tradition, in his mosque. This invitation was followed by a cordial yet contentious dialogue, ending with Muhammad's proposal that the Christians and he enter into a test of mutual cursing to see who professed the true faith. According to Muslim tradition, the Christians refused out of fear but returned completely unharmed to their land.

This would not quite pass for "dialogue" in the modern sense of the word. Nonetheless, in its day it was clearly a moment of encounter in profound mutual respect.

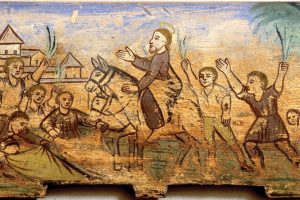

Six hundred years later, during the legendary visit of St. Francis of Assisi to the court of the Egyptian Sultan al-Malik al-Kamil in Damietta, we see a moment in which the two story lines of conflict and dialogue intersect. Francis went to preach the gospel to the sultan, fully expecting to receive the crown of martyrdom in return.

Having denounced the Crusades as mercenary, brutal, and un-Christian, Francis was determined to make his way through the clashing fleets of the Fifth Crusade to witness to Christ to the sultan. As the story goes, Francis offers the sultan the opportunity to participate in a test of walking through fire. According to one account the sultan refuses but sends the friar away with his blessing and protection.

This story describes a moment when sincere and respectful dialogue took place almost literally in the midst of bloody confrontation. In this way, the story of Francis before the sultan is a metaphor for the entire history of Christian-Muslim relations as one of both conflict and dialogue.

Building peace

If there has been a single most important turning point for the better in the history of Catholic-Muslim relations, it would be the Second Vatican Council and its 1965 promulgation of Nostra Aetate. The third section of this important document deals with the church's relationship with Islam and basically makes two critical points.

The first is to express "esteem" for Muslims and to emphasize the commonalities shared by Islam and Christianity as religions devoted to the worship of the one God and Creator of all things. The second is to call on Christians and Muslims not to be held captive by past conflicts and injuries, but rather to commit themselves to the preservation and promotion of "peace, liberty, social justice, and moral values."

The good news is that Christians and Muslims have responded enthusiastically to this call. In May 2006 an international conference in Chicago sponsored by Catholic Theological Union's Catholic-Muslim Studies Program brought together dialogue leaders from four different regions of the globe: Indonesia, Israel and Palestine, Nigeria, and the United Kingdom. The conference provided proof that the dialogues in each of these areas are thriving, although against tremendous odds.

There are without a doubt people with talented and able leadership in each of these regions who are deeply committed to Christian-Muslim dialogue, not only as a means of working toward a resolution of local religious conflicts but as a global peace-building movement posing a direct counter-point to self-fulfilling "clash of civilizations" mentalities. All the conference participants agreed, however, that the steady involvement of more and more people in the dialogues is critical if they are to succeed against the onslaught of extremism on both sides.

Bump in the road

Catholics and Muslims experienced a crisis prompted by remarks of Pope Benedict XVI in a lecture last September on faith and reason at the University of Regensburg. As widely reported, in this speech the pope quoted the words of a 14th-century Byzantine emperor, who had said that whatever new the Prophet Muhammad had brought was "only evil and inhuman." While a small percentage of Muslims responded to the pope's remarks in anger and with isolated incidents of violence against Christians and Christian sites, a vast majority were simply hurt, confused, and felt a certain degree of betrayal and foreboding.

Many were asking themselves if this was a sign that the Catholic Church was changing course from being a stalwart agent for global peace and reconciliation to taking sides in a "clash of civilizations." The reaction of the Vatican was swift and to the point: The pope expressed profound sorrow for having offended Muslims across the globe and stated his commitment to dialogue by repeating on a number of occasions his pre-crisis reference to Nostra Aetate as the "Magna Carta" of Christian-Muslim relations.

In the midst and aftermath of the Regensburg controversy, some Catholic theologians and columnists have attempted to spin Benedict's approach to Islam. In a New York Times op-ed column, Vatican correspondent John L. Allen Jr. claimed that the pope wants "dialogue with teeth." He provocatively cast the pope as a "hawk on Islam" and the Vatican's top Islamicist, Archbishop Michael Fitzgerald, current ambassador of the Holy See to Egypt, as a "dove."

Such statements not only caricature and thus dismiss the wealth of gifts men like Pope Benedict and Archbishop Fitzgerald bring to the dialogue, they also miss what distinguishes the language of authentic dialogue from the language of polemic and debate, which is so closely connected to the language of heresy.

The goal of debate is to win, to demonstrate that one's position is superior to that of one's opponent. In debate and polemic there is no intent to establish a meaningful relationship with the "other." In fact, on the human level, the outcome of most debate is estrangement. The purpose of authentic dialogue is precisely to establish a relationship between the dialogue partners-ideally a relationship of trust and love based on mutual understanding.

Indeed, if trust and love are not established, dialogue can never mature to the point where it can deal effectively with the difficult issues that stand in the way of good human relations. As Pope Benedict himself has reminded us, authentic dialogue can never be superficial. It must hold sincerity and candor as two of its highest values, and therefore must never fail to address the difficult issues. At the same time, however, dialogue can never rise to this important task unless it is conducted in the context of living human relationships characterized by trust and, in the pope's own words, "mutual respect."

Making amends

Benedict seems to understand this, as evidenced by his trip to Turkey late last year. Although the journey was primarily designed as a pilgrimage dedicated to furthering ecumenical reconciliation and dialogue with the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople, it was clear that Benedict also used it as a chance to mend many of the fences of Catholic-Muslim relations broken by the Regensburg lecture.

Echoing once again the teachings of Nostra Aetate, the pope stated clearly in his address to Shaykh Ali Bardakoglu that Christians and Muslims share a sacred responsibility in their respective offers of "a credible response which emerges clearly from today's society, even if it is often brushed aside, to the question about the meaning and purpose of life." He went on to say that Christians and Muslims "are called to work together, so as to help society to open itself to the transcendent, giving Almighty God his rightful place."

Yet, as powerful as these words of Benedict are, they paled in comparison to a simple gesture that, for many Muslims in Turkey and the world over, spoke volumes. Benedict, at the invitation of Shaykh Mustafa Cagrici, chief mufti of Istanbul, stood beside him before the beautiful prayer niche of the famed "Blue Mosque," placed his forearms and hands across his upper waist as Sunni Muslims do in prayer, closed his eyes, and joined the mufti in a brief moment of silent reflection.

There can be no doubt that the two narratives of the history of Christian-Muslim relations continue to unfold. There can also be no doubt, however, that since Vatican II, Catholic teaching has been clearly and consistently calling the church to reject any further active engagement in the story line of conflict, and instead to embrace fully what must be its central role in the story of dialogue and cooperation.

Add comment