The last time I attended a Mass in the older Latin rite, it was for the funeral of a friend. Tom was a difficult man in many ways, a war veteran whose stories about Vietnam were tinged with trauma and whose relationships with others were fraught. Yet he was also a delightful person, a music lover and natural rebel with no qualms about calling out hypocrisy.

Tom was estranged from his family, but they did arrange his funeral, which took the form of a traditional Latin Mass, or Tridentine Mass, as it is sometimes called. The liturgy was dreary, not in an appropriately funereal way, but as though the celebrant was trying to rub it in our faces that Mass should be formulaic, hierarchical, and forbidding. I half expected Tom to leap from his coffin in outrage at such a miserable sendoff and demand that we liven things up with some rock ’n’ roll. I left Tom’s funeral irritated on his behalf.

Later, I realized it wasn’t the liturgy that was the problem, but the way it was celebrated. The older form of the liturgy does not have to be stiff and formulaic, and I’ve been to some Tridentine Masses that were feasts for the senses. Yet the older rite is often associated with ultra-conservative ideologies, and most communities that celebrate it embrace reactionary views, leaving little space for a justice-oriented faith.

I used to be a traditionalist myself and would drive over an hour to find a Tridentine liturgy. Now I’m a progressive feminist who likes my church egalitarian and my theology liberative. Yet I am still drawn to the traditional Latin liturgy, and not just for the aesthetics. The Tridentine rite can be an expression of the church’s mission to unite all creation in an equitable peace and harmony amidst diversity. We miss out on the full significance of the traditional Latin liturgy when we reduce it to a static time-capsule or define it by ultra-traditionalist interpretations of the faith.

Traditionalist Catholics often talk as though the old Mass never changed over the years, and thus offers a ritualistic line of connection from the present to the age of the apostles, but this is inaccurate. The earliest Christians had different eucharistic rites, in many different languages. Eventually things were standardized, and by the late fourth century, Latin was the official church language. But the Tridentine rite wasn’t codified until 1570, at the Council of Trent—thus the name, Tridentinus, “of the city of Trent.” Pope Pius V, who presided over the council, wanted to emphasize unity, since many different liturgies had proliferated over the centuries.

Still, a time traveler to the European Middle Ages who popped into a church for Mass would find something more like the Tridentine rite than the new rite as established at the Second Vatican Council. The older rite uses medieval Latin instead of the vernacular. The entire ritual is different: the wording, the ordering, the responses. The celebrant does not stand on the other side of the altar, facing the people (versus populum), but stands with his back to the congregation (ad orientem—literally, “to the East,” since it was traditional in many cultures for churches to face that direction). There’s often chanting and incense. The language is ornate and poetic, but with less participation than in the newer liturgy. Often, the priest chants the eucharistic prayer quietly, while the congregation prays in silence. And people receive communion on the tongue, not in the hand, as they kneel along an altar rail.

If you go to Mass in a traditionalist church, you’ll probably see women with their heads covered, maybe with hats or with long lacy mantillas or doily-like toquillas. For centuries before Vatican II, this was the rule. I remember my Jewish grandfather explaining why his family’s millinery shop went out of business: “The pope told women they didn’t have to wear hats anymore.”

I understand and value the liturgical changes made at Vatican II, but I’d also like to see some of those themes of renewal connected with the older rite. My ideal parish would have traditional aesthetics, including the old rite Mass on occasion, but without the rigidity of traditionalism. The congregation would be more involved, and the aesthetics might incorporate musical and artistic trends from an array of cultures, not just European ones. We’d have women in ministry, programs for community outreach, and well-trained homilists connecting the Mass readings with the church’s gospel call. It would be an accessible space that welcomed diversity of cultures, ethnicities, and family types. Queer Catholics would find a home there, too.

I don’t envision the lush formality of the Tridentine rite undercutting this inclusive vision. While many prefer to hear Mass in the vernacular, I like how using church Latin signifies equality and unity, across the fabricated boundaries of nation states or class division. We may think of Latin as fancy, but it really isn’t. When the church was born, Latin was the language of the people, in use across the different nations conquered by the Romans. Using Latin in liturgy could theoretically send a message that “this is the empire now,” and unfortunately, the church has had identity crises along those lines. But the message could also be, “whatever nation you belong to, whatever laws bind you, you are children of God.”

I don’t mind the priest standing with his back to the congregation, either, as long as everyone is able to hear and participate. As Bishop James S. Wall wrote, reflecting on Pope Benedict XVI’s theology of liturgy, “ad orientem worship shows, even in its literal orientation, that the priest and the people are united together as one in worshipping God.” This blurs the clericalist separation between the priest and the people. When the priest approaches the altar, he does so as one of us. Our theology of baptism teaches that every Catholic is “priest, prophet, and king,” and the choreography of the older rite could emphasize this.

As for the ornate, sometimes formal aesthetic, I don’t think it’s superior, or that God is somehow more pleased by Gregorian chant than folk music. Nor do I think God wants or needs the clergy to be decked out in expensive finery. Plenty of people prefer casual guitar masses and felt-banner décor, associating them with a mission-driven church that spends its wealth caring for the people, not dressing up. But traditional aesthetics have a place too, especially as they establish church as a sacred space.

Often when we think of a space as sacred, we imagine this in terms of the forbidding or the forbidden. But a sacred space inhabited by a God of justice is a space of welcome, protection, and peace. The ancient tradition of churches as sanctuaries rests on this idea. In the sacred space, the world’s rules no longer apply. Authoritarian structures are inverted or laid low. The last are made first, the mighty are cast down.

The pointed arches of gothic architecture draw the eye upward toward heaven, which emphasizes transcendence, as opposed to later architectural styles that speak to God as present. Transcendence, in the Christian vision, does not undercut immanence. But the gothic pinnacles pointing toward another world tell us that this is not all that there is—whatever pain and sorrow we endure here, we have hope that it will be made right. We look up, from the chaotic kingdoms of this world to the peaceable kingdom we are promised.

Traditionalist Catholicism tends to romanticize the medieval era as a time when everyone was pious and well-behaved and orderly. But this was an era of extreme ecclesial corruption, since the institutional church wielded a great deal of power, and power corrupts. Those who want to get rid of separation of church and state, and point to the Middle Ages as an ideal, don’t know what they’re asking for.

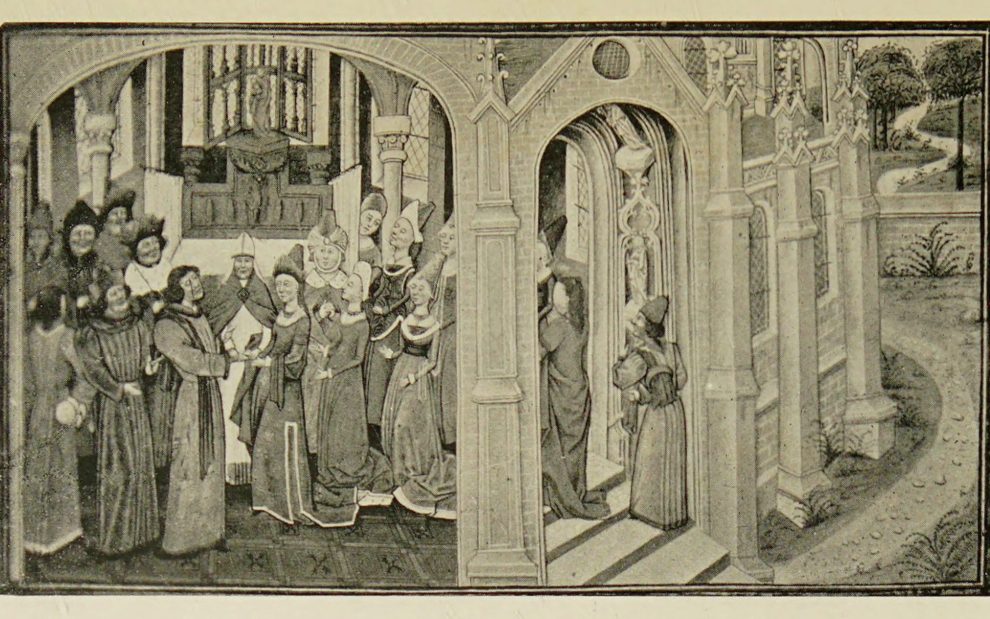

Yet there’s something about the messiness of medieval Catholicism that appeals to me. The sacred space was the hub of the entire culture. People went to church to keep the feasts and pray and give thanks but also to get a break from work, do business, plot politics, gossip, and flirt. The sumptuousness of traditional aesthetics can speak of this incarnational view of the world, pointing to a theology of excess and abundance, reminding us that God is present where least expected, where the lines between the sacred and the profane get blurred.

I think my friend Tom would have liked it.

This article also appears in the February 2026 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 91, No. 2, pages 21-22). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: from Parish priests and their people in the Middle Ages in England, 1898, Rev. Edward L. Cutts

Add comment