The church is often imagined as a pyramid, with the pope at the apex, priests somewhere around the middle, and laypeople at the base. This image reinforces the idea that the church is a top-down power structure, a model the Synod on Synodality logo would have us rethink. But long before the Synod on Synodality, the church already understood its members as equal—many parts make up the one body of Christ (1 Cor. 12:12–27). Catholic perspectives on Christian baptism underscore this equality.

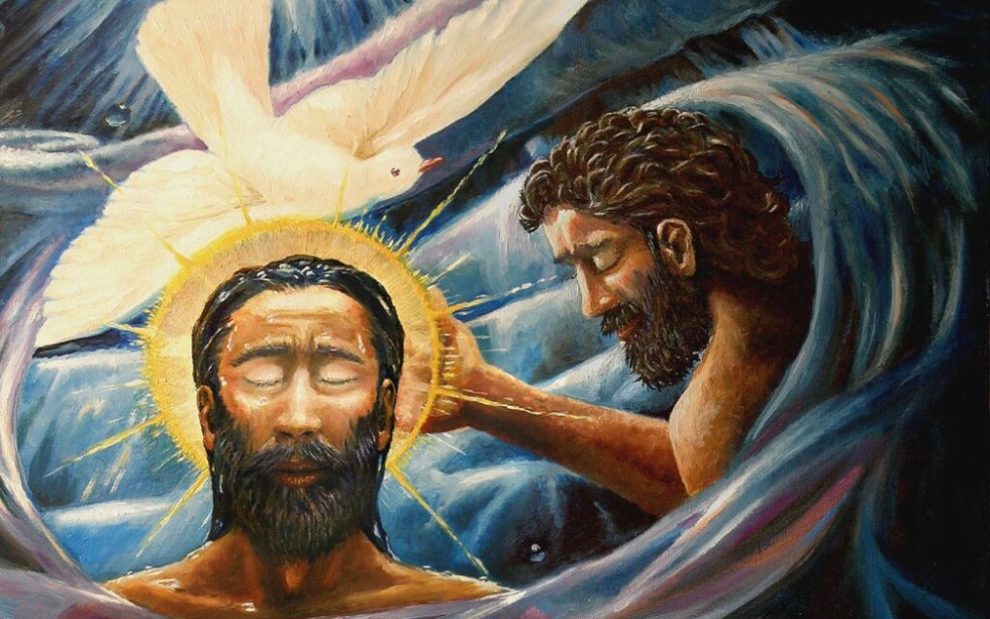

The gospels describe John the Baptist’s baptism as one of “repentance for the forgiveness of sins” (Mark 1:4), and many Christians tend to focus on this aspect of the sacrament. Yet Christ also sought baptism from John—and our church tradition is clear that Jesus was sinless. According to the gospels, the purpose of his baptism was to “fulfil all righteousness” (Matt. 3:15). Looking more closely at Jesus’ baptism can inspire us to live our own baptism more fully—and the lens of solidarity can help us see Jesus’ baptism more clearly.

The call to solidarity

Pope John Paul II describes solidarity as “a firm and persevering determination to commit oneself to the common good; that is to say, to the good of all and of each individual, because we are all really responsible for all.” Pope Francis says solidarity “means much more than engaging in sporadic acts of generosity. It means thinking and acting in terms of community and confronting the destructive effects of the empire of money.” Christ’s baptism—which is our sacramental baptism—calls us to be in solidarity with what the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) calls our “one human family.”

Sadly, sometimes solidarity seems to be an elusive hope. Our one human family finds itself suffering in unspeakable ways. War tears through many parts of the world, poverty crushes more than half of the Earth’s population, and recovery from the climate crisis seems more like a faraway dream than an achievable reality. In the United States, immigrants are being victimized, abused, and unjustly deported; families are being separated; and systemic racism is tightening its grip on the nation’s conscience. Women, young people, and people of color invariably experience these issues’ worst effects.

Meanwhile, our global economic system—the empire of money—moves like a runaway train, with little intention of prioritizing people over profits. At this point, it is impossible to reconcile unchecked capitalism with the dignity of the poor and marginalized. Injustice may be the greatest marker of this moment in history, mostly due to the greed of a few, enormously wealthy individuals. Consuming the news these days is almost like asking to be overwhelmed with dread.

Participation in Jesus’ ministry

When Jesus asked his cousin John to baptize him, he was joining a fringe, marginalized crowd, proclaiming God’s challenge to excessive wealth and individualism. Through Jesus’ baptism, God opens an invitation for humanity to enter into this same new experience of Divine love.

Christ’s baptism, which marked the beginning of his public ministry, reveals that justice and peace are the heartbeat of Christian solidarity. Jesus’ zeal for justice and peace—his solidarity with the poor and the marginalized—contributed to his public execution on the cross. Baptism, like all the deepest mysteries of our faith—the birth of Christ (the incarnation), the crucifixion, the resurrection, and Pentecost—points to the same truth: God is in solidarity with the poor and the marginalized.

Our own baptisms invite us to join Christ’s public ministry. As the body of Christ, we are responsible for continuing his mission when he was on Earth. Living out our baptisms in our own unique, authentic ways helps the church join Jesus’ movement for justice and peace. Our solidarity with Jesus and the oppressed develops from an invisible virtue into visible impacts through the wisdom, creativity, and compassion that come from addressing the causes and effects of injustice in our communities and the world.

Getting involved in ministry is one of the best ways to make sense of our baptism. In Matthew 25, in what church tradition calls the corporeal works of mercy, Jesus describes opportunities to work for justice and peace, starting first with the poor. Because we are all equal through our baptism, we all share the responsibility of carrying on Jesus’ work; ministry is not reserved solely for the clergy or a few elite members of the church.

Opportunities for ministry

Because we are all so different, there is no single “correct” way to follow our baptismal call. God creates each of us with individual gifts, talents, abilities, and life experiences that prepare us for the Divine call (our vocation) in our lives. Moreover, the church supports countless ministries that address the needs of the poor and the marginalized; the USCCB’s website offers many practical ways to make a difference, including ministries to prisoners and migrants, catechesis (teaching and accompaniment), and advocacy. Even children can be involved in ministries like altar serving and reading.

Your personal individuality is exactly what our church needs. Christian baptism recognizes each person’s God-given dignity, so factors such as your race, age, gender, or abilities help the Holy Spirit enrich our church through you. Christ’s baptism means God depends on all of us to continue the work of salvation that Christ started.

Catholic examples of solidarity

Many Catholics meaningfully engage with their baptism and enter into the solidarity that Jesus offers through baptism. Christian solidarity is made visible in the lives of these ordinary people who follow Christ in their daily lives. Dorothy Day (1897–1980), for example, a journalist and activist, advocated for justice and peace and co-founded the Catholic Worker Movement in the United States during a time when women’s voices were largely ignored. Paul Farmer (1959–2022), a physician, a teacher, and another example of Christian solidarity, brought desperately needed, community-based health care to the poorest people of the world in countries such as Haiti and Rwanda.

Today, we also see Christian solidarity in action in people like Mikhail Woodruffe (b. 1988), a Carmelite priest and social worker; through community outreach and ecumenical, faith-based action, he empowers the communities of Trinidad’s Maracas Valley to fight poverty and gang violence. Perhaps we see the best examples of Christian solidarity in parents who work tirelessly to raise their children well, or the staff of neglected parishes who continue to serve the needs of their communities.

The challenge of baptism

Baptismal solidarity calls us to reframe how we approach contemporary issues. It asks us to orient ourselves with the poor and the marginalized, rather than aligning ourselves with partisan ideologies. No person is more baptized than another. The rich do not get to enjoy a different baptism from the poor; men are baptized into exactly the same baptism as women; clergy are not more blessed than laypeople. Baptism shows us that the most marginalized person in our church shares equally in the same dignity as the holiest saint in our tradition—and they ought to be treated as such. Discrimination of any kind hinders solidarity. It prevents us from being responsible for all.

Baptism continues to raise unresolved questions: for instance, can our church justly deny God’s call to the priesthood or diaconate because the person is not male? Does the baptismal promise that we are “no longer male or female” (Gal. 3:28) stop at the masculinity of Christ? If our church could shed its patriarchal chains, it would embrace Christian solidarity in an even deeper way.

The salvation we find in Jesus begins in solidarity with our human family, rooted in our baptism. When we meaningfully engage with our baptism, God awakens the Spirit’s call in our lives. Ultimately, baptism is a call to trust the Holy Spirit and believe in the goodness and dignity of humanity.

And one thing is certain: A renewed engagement with our baptism inevitably helps us hear God say, “You are my beloved child.” How will we live out this identity?

Image: David Zelenka, CC BY-SA 3.0

Add comment