Written during and after the sack of Rome, the empire that was supposed to last forever, St. Augustine’s City of God is based on a fundamental idea about how societies work. People are united, he says, because of common objects of love.

This is a powerful idea. It sheds some light on the current social division in our nation by simply pointing out that unless people love things in common, they can’t really be a society. Today, more and more people define themselves by who and what they are against, us-versus-them, even within a single country.

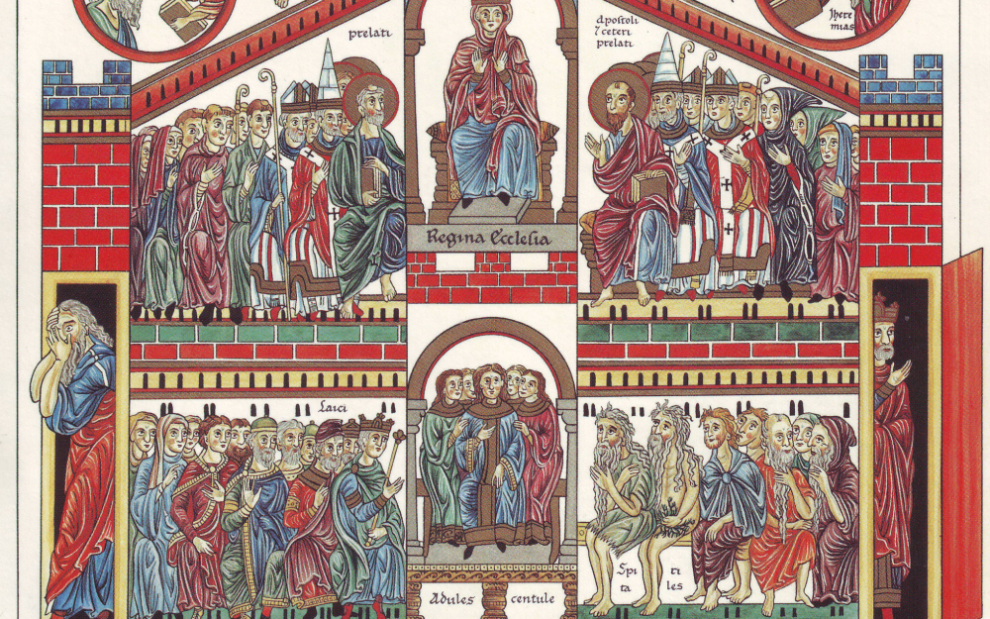

In City of God, Augustine analyzes two cities, the earthly “city of man” and the heavenly “city of God.” Rather than a spiritualized escapism from social conflict, we should see this analysis as the true key to addressing social conflict in ways that lead to genuine peace.

Augustine always sought deeper explanations rooted in the human heart. For him, the two cities weren’t actual places but were like the weeds and the wheat growing together, even in the same heart. In the earthly city, the love that held people together was ultimately a love of self. Admiring those who seek monetary gain, the honor of high position, the glory of military victory, or the “immortality” of fame, the human city ultimately was built on love of self at the expense of love of God and neighbor.

Augustine claimed that even the most noble actions of the Romans were motivated by self-seeking, by vanity and glory. Only the city of God, built on shared love of God and of all neighbors as loved by God, could endure; any other city would fail to hold together, because love of self eventually produces division.

In a time of turmoil, each of us is faced with a similar dilemma. It is no doubt one of the reasons that Pope Francis gave the 2025 Jubilee Year the theme of hope. Our objects of hope are those things that become our objects of love when we are fully united with them.

Do we place our hope in things that are ultimately about love of self—pride in our own identity, greed for our own gain, glory for our own group? As these fail, we invariably arrive at dead ends, whether those are a cycle of anger and bitterness, an escape into trivial or numbing pleasures, or a simple inability to summon the energy to care about what is right in front of us. We face a choice: Where does our heart truly lie?

Pope Leo XIV has continued using the weekly papal audience to catechize on hope, with a recent focus on the gospel readings around Jesus’ passion and death. This is the quintessential moment of despair and division in the New Testament. Where must hope lie in such moments?

Leo shows himself to be a profound son of his spiritual father, Augustine, for he insists that our hope rests nowhere but on God’s love in Christ. Leo’s episcopal motto is: “In the One [Christ], we are one.”

During a recent audience, Leo spoke about how, in the garden at Gethsemane, Jesus reveals that the “true essence of hope is the firm conviction that even in the midst of violence, injustice, and suffering, God’s love is ever present as a source of spiritual fruitfulness and the promise of eternal life.” In other words, as Pope Leo said during the Jubilee gathering of youth in Rome, “everything in the world has meaning only insofar as it serves to unite us to God and to our brothers and sisters in charity.”

As Pope Benedict powerfully taught in Spe Salvi, his encyclical on hope, “eternal life” is not some individualistic eternity but rather is fundamentally a social hope of the gathering of the whole human race into one community. Hope for that ultimate community means that we will “grow in compassion, kindness, humility, meekness and patience, forgiveness and peace, all in imitation of Christ.” Being hopeful in a violent world means eschewing counter-violence, which is ultimately love of self over and against neighbor.

A real growth in hope in God means we will be better able to love our neighbor. And this is because we discover that God loves us, even when we are drawn to other loves. In Leo’s catechesis on the apostles’ betrayal of Jesus, he concentrates on the apostles each questioning whether they would be the ones to betray Christ at the Last Supper, asking, “Surely it is not I?” While this is not a phrase admitting guilt, Leo interprets it as conveying a sense of fragility and vulnerability. In their words, we recognize that we too might well be capable of such betrayal.

Yet, the pope says, Jesus remains at table with them, and with us, despite the coming betrayal. “Salvation begins here: with the awareness that we may be the ones who break our trust in God,” Leo says. “Ultimately, this is hope: knowing that even if we fail, God will never fail us.”

Leo notes that the worldly way of dealing with evil is judgment and accusation, but God faces evil differently. God accepts suffering and grieves for evil without seeking to avenge it. The pope then invites us to grieve as well, both for ourselves and for others. For, “precisely there, at the darkest point, the light is not extinguished. On the contrary, it starts to shine. Because if we recognize our limit, if we let ourselves be touched by the pain of Christ, then we can finally be born again.”

Pope Leo’s words may seem a bit distant from the hard realities of social division. But in fact, they illuminate every choice we make about what our true objects of hope and love are. Leo challenges us: Do we believe that God as revealed in Jesus is really always present, ever faithful, and ever calling us to an imitation of Christ? And when we recognize the real possibility of evil in ourselves (not just in our social enemies), do we believe that God is waiting not to judge us, but to turn us around and make us live anew?

If we believe these things, we will approach our social division in a different way, and we will never lose hope.

This article also appears in the December 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 12, pages 40-41). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Herrad of Landsberg, from Hortus Deliciarum, circa 1180. Wikimedia Commons.

Add comment