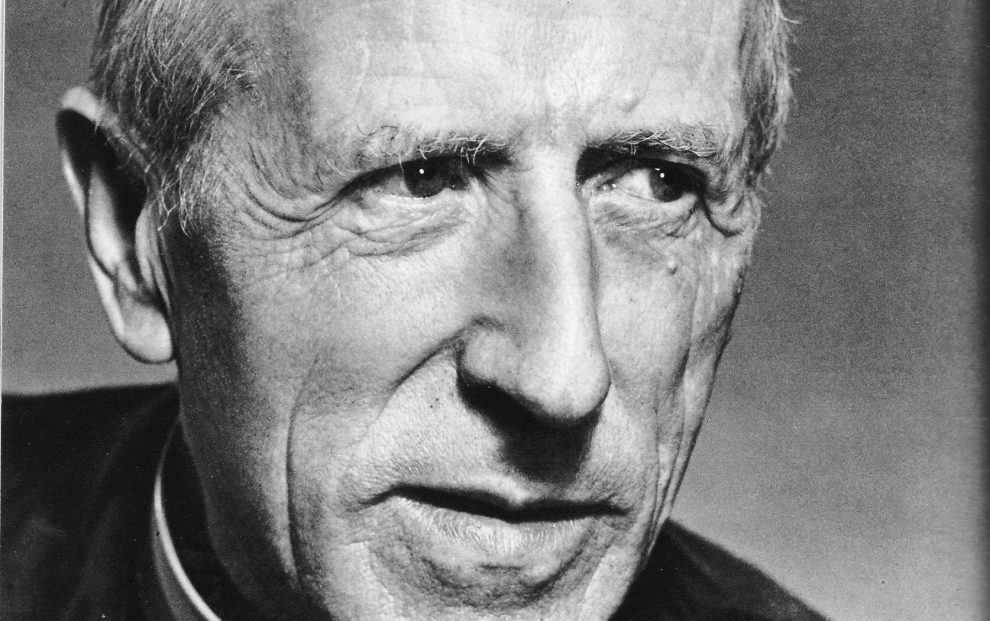

In Laudato Si’ (On Care for Our Common Home), Pope Francis explicitly evoked the Christo-cosmic vision of the French Jesuit paleontologist and theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, writing that the “ultimate destiny of the universe is in the fullness of God, which has already been attained by the risen Christ, the measure of the maturity of all things.” Teilhard spent more than two decades conducting geological and paleontological work in China, in close collaboration with Chinese colleagues. His vision was shaped by a profound encounter with the people, geology, and material culture of China.

Known as 德日进—the three Chinese characters meaning “virtue, sun, progress,” translated as “Father Daybreak Virtue”—by his Chinese collaborators, Teilhard served as an adviser to the Geological Survey of China. In the 1930s, Chinese archaeologists discovered Peking Man, a subspecies of Homo erectus, human ancestors who lived about 400,000 years ago. Teilhard considered the shared discovery of Peking Man the most decisive event of his career—an “awakening” to the history of life, the ceaseless movement of evolution, and the deep kinship of all creation, which “madly” increased his “faith in the presence of God in our lives.”

Growing up in China, I first learned about Peking Man when I was around 10 years old. But it took me 15 years to finally visit the site, and five more to recognize the profound significance of Teilhard’s work. Teilhard himself was drawn to “things”—or more correctly, to something that “shone” at the heart of things—when he was no more than 7 years old. That was the beginning of his spiritual evolution.

Like Teilhard, who dreamed as a child of a consistency among things, I too dreamed of becoming a scientist at the dawn of reason and committed myself to discovering the theory of everything. Yet unlike Teilhard, whose early religious life as a young scientist developed under the sign of the Heart of Jesus and gradually transformed into a cosmic vision in which all is love, my religious awakening felt like a violent and painful rupture from my childhood commitment to science.

Awakened to the reality of human love and carried away by a profound faith—now defined by the figure of Jesus Christ—I chose to give up the path of graduate study in science and entered theological school instead. I mourned a dream that died without ever being realized. Gradually, however, I began to find peace in my loss, consoled—as Teilhard was—by the Heart of Jesus.

Despite all my theological training, my first real encounter with Teilhard was through my husband, Andrew, a scholar of Chinese archaeology. Perhaps it was truly providence that this nascent childhood passion was rekindled by a human love, which returned me to the love of God and to the church, whose heart, as St. Thérèse of Lisieux wrote, is “burning with love.” I am making my way into a world whose horizon has been opened, universalized and centered by Teilhard as one “WHICH I CAN LOVE.”

Teilhard perceived the Heart of Christ as a “fire with the power to penetrate all things.” At the root of this vision was a fidelity to the divine will that undergirded his spiritual life. This eminently Christian attitude, he wrote, “connected my love of Christ and my love of [t]hings. Nevertheless, I have always, ever since the first years of my religious life, gladly surrendered myself to this active feeling of communion with God through the [u]niverse.” Often overlooked is that Teilhard’s “pan-Christic” mysticism emerged and took form in China.

While Andrew’s knowledge of Teilhard came from recent turns in Chinese archaeology, geology, and paleontology to rediscover their own intellectual history, my encounter with Teilhard through him marked the beginning of an irrevocable return to the heart of my own childhood in China—and a deep dive into the Catholic and Chinese traditions that continue to nourish my growth. The innocent dream of my earliest days has long been forgotten. In its place is the “consistency of the universe,” awakened in me by Teilhard.

After leaving China to pursue higher education in the United States, where confusing geopolitical tensions often prevail, I am slowly gaining clarity through Teilhard’s sage wisdom. China, for Teilhard, was not merely a place of exile and misfortune—it was the principal setting for the inception of his most important writings, including

“The Mass on the World,” “The Divine Milieu,” and “The Human Phenomenon.” China became for him a calling, a blessing, and a source of inspiration—opening a horizon of universal love.

He went to China in obedience to what he called the “mysterious Affection of the World to serve and to make serve” and “in the hope of better feeding this inner flame at all the great sources of inspiration of the Earth.” There, Teilhard discovered the one thing that truly inspired him: “to recognize and reveal that specific and essential element which the East must bring to the West so the Earth will be complete.” He called this “the Note of China, the Note of All” and located it at the center of the divine milieu—identified with Jesus Christ.

Teilhard paved the way for me to return—to China, to the immensity of the world, and to the depths of my own heart—so that I might discover that the mystery of the universe, the mystery of Christ, and the mystery of the church can be described in a single word: love. In the last century, Teilhard sparked a new spiritual and intellectual movement among Chinese thinkers and within the Catholic Church. Today, his insights continue to inspire creative endeavors in spirituality, ecology and theology—illuminating the path of global collaboration in caring for our common home, fostering a culture of encounter, and building a civilization of love.

For me, the most prophetic of Teilhard’s contributions is his vision of a great convergence between East and West—a vision first realized in his life through his faithful obedience to the attraction of his own heart. In his exhortation Dilexit Nos (On Human and Divine Love), Pope Francis wrote that Christ is the heart of the world, the center of history, and the inspiration for all of us to journey toward a more just, united, and loving world. He called us to rediscover the importance of the heart.

Yet a heart cannot be complete without encountering others, without loving all the children of the Earth, and without resting perfectly at home in the universe and in God. Only then can the coming of the future be actualized—when we can see “in the World a mysterious product of completion and fulfillment for the Absolute Being.”

This article also appears in the October 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 10, pages 45-46). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Archives of the Jesuits of France

Add comment