I had the dream again the other night, one I’ve had a hundred times over. I’m at school but not in class. Rather, I’m at my locker, desperately trying to find my class schedule. I know I should be in class right now, but I don’t know which one. I don’t even know which building I should be in, who the teacher is, or what I should be learning. Is it math, science, literature, or something else? Fear rises in me as I realize I can’t possibly pass a course I’ve never shown up for. Where is it I’m supposed to be? What is it I should be learning?

I always wake up in great distress. It’s a fear-of-failure message, of course. Such fears are common in a stress-filled century like ours—or perhaps any century you could name. Maybe our ancestors woke up in a cold sweat about crop failures or armies breeching poorly constructed city walls. Our modern terrors are about being pink slipped in the next round of company budget cuts or not keeping up with the constantly evolving skill set necessary to do the job we’ve being doing for years.

Anxiety, confusion, and a deep sense of inadequacy have likely haunted mortals from the first failure of original sin. We’re not good enough is now burned deep into our psyches. Knowledge of our limitations is a very vulnerable self-understanding with which we are perpetually burdened.

This month, the Sunday gospels all seem to touch on this business of our unpreparedness for the life we’re living, how unqualified we seem to be for the Christian path we’re supposed to be on. Jesus spells it out in numerous parables: To be ready for whole-souled discipleship, we must be prepared to “hate” our families. Even if we embrace the Semitic hyperbole of this “hate,” who among us will choose the eternal demands of Jesus over our family’s immediate needs? Most of us opt for family every time.

Yet Jesus persists: Who would begin to build a tower they don’t have the means to finish? Who would start a war they know they can’t win? We do. All the time. Have you ever bought a gym membership you didn’t use or invested in supplies for a hobby you quickly abandoned? Have you ever entered into an argument with more emotion than information?

Jesus doesn’t let us off the hook. He tells about a dishonest steward who gets caught with his hand in the till and who then cheats his way out of the mess he just cheated his way into. As with many parables about folks who do the wrong thing—the sower wastes his precious seed on unpromising soil, the shepherd leaves 99 sheep to go in search of one stray, the employer returns home to wait on his house staff, the landowner pays long- and short-term workers the same wage—Jesus insists on admiring people we find distinctly unadmirable.

In this instance, Jesus holds up the dishonest steward as exemplary because of his remarkable consistency. This scoundrel is true to what he believes in most, which is cheating. The cheaters of this world, Jesus affirms, show more integrity than we who profess faith in God’s ways but act out of self-interest.

You can’t serve God and money, Jesus declares. Still, we give this tandem loyalty our best shot. When an editor asks me to soften a challenging essay so readers aren’t offended and cancel their subscriptions, I do it because that’s what I’m paid to do. (FYI, editors at U.S. Catholic never ask me to soften anything!) I know a few pastors who’ve watched members of their assembly walk out of Mass because the homily made them mad. But I know many more preachers who deliver only easy words and withhold challenging ones, because they don’t want to take the ugly phone calls and lose parish revenue.

Is it any wonder we have fear-of-discipleship-failure? How can we possibly live up to the things we profess in every creed and affirm with each sacrament? How can we be disciples of a Lord who asks for what we, in the land of abundance, are pretty much resolved not to hand over?

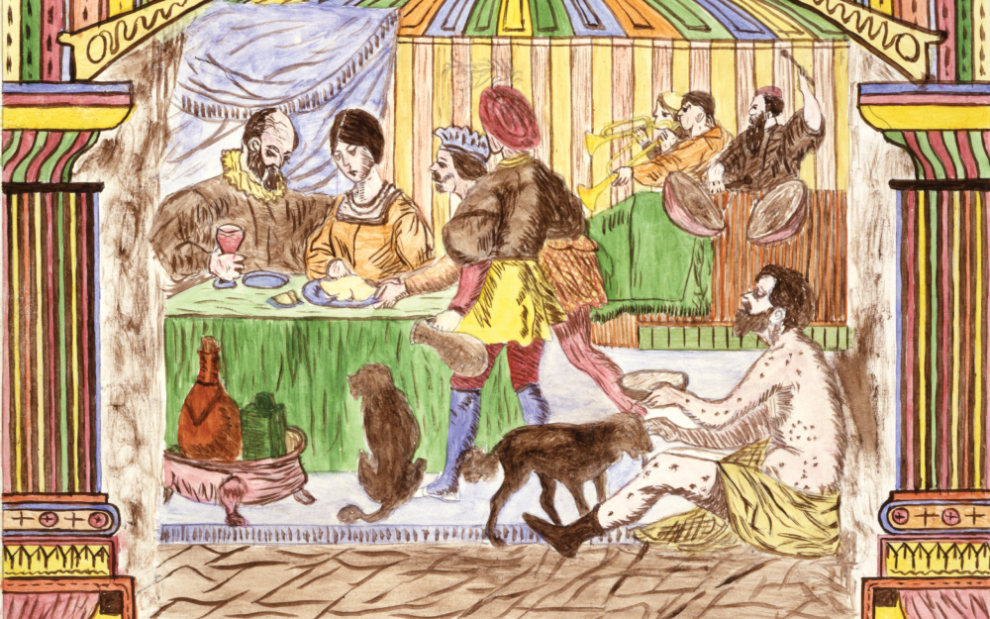

Personally, I admit to feeling like the rich guy in the parable who dresses in purple and dines with gusto while poor Lazarus, covered in sores, dies of starvation and lack of care in his doorway. I may extend myself in the rare heroic gesture: writing a check for victims of a fire or serving a meal at a soup kitchen. But I am not like the dishonest stewards of our day who deceive with great pleasure in front of the cameras while plundering the planet’s natural resources like pirates. Instead, I whimper my coveted truths in a corner. I “wish” things were different than they are, rather than fighting with all my strength and blood and bones to make them so.

The hard sayings of Jesus propel me back into that ever-repeating nightmare, feeling sure that I’m not where I should be, not having learned the lessons I need to be an authentic disciple. In this case, of course, I know who the teacher is, and I have the textbook well in hand. But I’m missing something crucial, the most vital element of the curriculum of faith. Simply put, I lack the will of the saints to follow God wherever God leads. Fear of failure in this magnitude fills me with shame. As it should.

There are theological debates about the so-called “good-enough Christian.” This is the person who goes to church, follows the rules, and keeps their nose clean of the most egregious sins. The good-enough Christian permits themselves a little greed or a large share of self-absorption. Surrendered to God are the required churchy rituals and practices, the letter-of-the-law obedience signed off on in the contract of our baptism. The rest of the secular, workaday part of life belongs to the good-enough soul, by this reckoning. Moderation in all things, and let’s not take this religion thing too fanatically, shall we?

Perhaps we should take religion fanatically. This is the trepidation that spawns the nightmares: Maybe Jesus isn’t exaggerating any of the gospel demands. Maybe Jesus really does expect his followers to take religion seriously—all the way to the cross, as he did. The Exaltation of the Cross is on the calendar for this month too, sorry to say: a liturgy that includes Paul’s declaration that every knee must bend and every tongue profess the sovereignty of Jesus. I fear that being a good-enough Christian isn’t good enough in light of this teaching.

In our Jubilee Year of Hope, I seek the light at the end of this particular tunnel of so many Sundays of demanding readings. I find it on the Sunday of the Exaltation of the Cross, when John’s gospel tells us that the Son of God doesn’t come into this world to condemn the world but to save it. Which is to say, to rescue us from the shamefully inadequate limitations of our superficial religious commitment.

Jesus has already done the heavy lifting of saving the universe by embracing “even death, death on a cross.” But the cross of Christ is not to be mistaken for an E-Z Pass through our own vital responsibility to build a world of justice and peace. We cannot serve God and money, Christ’s way and ours.

This article also appears in the September 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 9, pages 47-49). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Lawrence W. Ladd, Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus, ca. 1880, watercolor and pencil on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Add comment