If Jesus were living in our modern world, would he have had the chance to go to college?

Jesus wasn’t born into privilege. In Luke 2:24, we learn that Mary and Joseph brought two doves to the temple. This sacrifice was not just a spiritual practice but also a significant marker of class. Jesus grew up in Nazareth, a marginalized village on the economic and geographic fringes of Galilee—overlooked by trade routes, underdeveloped, and marked by survival. Its economic blight caused the elite of the day to ask, “Can anything good come from there?” (John 1:46).

That question came from people with power, religious leaders, people with access to resources and respectability. They couldn’t imagine that anything sacred, powerful, or world-changing could come from a place that was challenged economically. But what they didn’t understand then and what many still fail to see is that value isn’t defined by economics, power, or position.

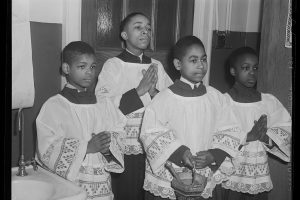

In many ways, Jesus’ social status mirrors that of those in neighborhoods where poverty is concentrated not because of a lack of potential, but because of a long history of economic exclusion and structural neglect. Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were founded to offer resources to people in those communities—in the face of enslavement and legal segregation and other systems designed to keep Black people from accessing education as a path to upward mobility.

Long before the Civil Rights Act, HBCUs provided Black people with opportunities this country systematically denied, offering a place to pursue higher education despite poverty and exclusion.

Yet HBCUs are presently at risk, due to policies of the current administration. The recent revocation of Executive Order 14041—which supported HBCUs and aimed to advance educational equity undermines one of the few national commitments to institutions that have long stood in the gap for those pushed to the margins.

Many HBCUs were established during Reconstruction and built by Black people—through Black churches, mutual aid societies, and with some support from missionary organizations. Black students could be seen, valued, and given the space simply to be, be fully and unapologetically, while learning. These were schools where anti-Blackness couldn’t silence ambition or discourage the educational dreams of students determined to rise from poverty.

HBCUs enroll approximately 9 percent of Black undergraduates and award around 16% percent of all bachelor’s degrees earned by Black students. Despite representing less than 3 percent of U.S. colleges and universities, these institutions are doing transformative work, often with fewer resources than predominantly white institutions. Nearly 73 percent of HBCU students receive Pell Grants, a reflection of how deeply these institutions serve students from low-income families.

Additionally, with less funding and fewer resources, HBCU schools continue to enroll, support, and graduate Black students at scale. They produce 40 percent of Black engineers, 50 percent of Black lawyers, and 70 percent of Black doctors and dentists.

Personally, I didn’t grow up knowing what an HBCU was—even though my mother graduated from one. She was a single parent after she graduated, working multiple jobs just to keep us (my sister and me) afloat, and we never had the space to talk fully about what it meant or the pride that came along with it, but she eventually achieved her doctoral degree in clinical counseling.

When you grow up in poverty, college doesn’t always come up as an option—not because it’s not important, but because survival drowns out everything else.

You don’t get to dream when your survival takes up all your energy. When your lights are off, you are worried about how you will eat, or you’re watching your little brother while your mother works the night shift—you’re not thinking about college essays. You don’t fill out the FAFSA when no one’s ever broken down what it is, or when your family doesn’t have the paperwork the form expects. You don’t apply to college when every brochure shows people who don’t look like you, and no one in your school has ever said, “You belong here.”

College starts to feel like a place built for someone else. Not because you aren’t capable, but because everything around you has made it hard to see that you are. My father never finished college, and none of the men in my family ever sat me down to talk about education as a way out. I spent years navigating concentrated poverty that was designed to keep someone like me from ever accessing higher education. I dropped out of high school. I experienced homelessness briefly as a teenager.

Today I serve as the Director of Public Policy and Social Change and a professor at Simmons College of Kentucky—an HBCU in Louisville—while also leading Love Beyond Walls in Atlanta. I’m the only man in my family with a Ph.D.—but that didn’t happen by accident. It happened through struggle, spiritual formation, and the kind of faith communities that saw worth in me.

Even though I didn’t attend an HBCU myself, I find myself, as a professor and director in this space, advocating for the access of young adults who also emerge from places littered with poverty and housing insecurity. HBCUs serve students who carry the weight of intergenerational poverty, housing instability, and the pressure of being the first in their families to try. I feel the sacredness of these spaces and the power of what they can provide.

Recently, I partnered with a social worker from Jefferson County Public Schools (JCPS) to ensure Simmons College had a presence at a local conference in Louisville for high school seniors experiencing homelessness. About 40 students came. Many had never set foot on a college campus. Some had never even heard of Simmons. A few didn’t know what the FAFSA was.

After the event, the social worker and I spoke. She told me many students lacked even basic college information not because they didn’t care, but because they’d never had someone walk them through it. They weren’t short on intelligence. They were short on access.

Federal support helps fund the very outreach and wraparound services that make college a reality for students who have been historically locked out. When that support disappears, HBCUs are forced to scale back essential programs—mentorship, academic advising, summer bridge programs, and first-generation student support—that help students persist and graduate.

If we really care about educational equity, HBCUs should be first in line for investment—not last.

When HBCU support is rolled back what gets erased is not just funds, but visibility and awareness. Not just programs, but presence. Not just opportunity, but hope. When policy revokes funding, it blocks futures and tells students in impoverished communities, “This isn’t for you.” It’s the same message, just dressed in policy—another way of saying, “Can anything good come from there?”

For me, faith doesn’t just help me make sense of the world, it pushes me to see what’s broken and respond. When I read about Jesus, I don’t see someone who protected systems that harmed people. I see someone who stood with the poor, questioned the powerful, and called out injustice. He didn’t just show up in hard places—he chose them. He didn’t avoid the margins—he came from them.

Yes, Matthew 25 reminds us: “Whatever you’ve done to the least of these, you’ve done to me.” But if we stop there, we miss something deeper. Jesus didn’t just care about the poor—he was poor. He didn’t just advocate for the excluded—he shared in their exclusion. And if he were walking today, he’d be with students in neighborhoods like mine, saying: You still matter, even when the system says otherwise.

These recent policy shifts betray the liberating message of the gospel—a gospel that centers the poor, uplifts the forgotten, and disrupts anything that stands in the way of dignity.

If you consider yourself a person of faith, this isn’t just a political moment—it’s a moral one. Because every time policy builds a barrier between a student and their future, it also builds a barrier between what we say we believe and how we choose to live. And its Black students—those from underfunded schools, unstable housing, and communities historically locked out of access to higher education—who continue to carry the greatest burden.

If we say we care about equity, justice, and faith, then we must care about Black access to higher education. Because when we invest in Black students and HBCUs, we are not just repairing systems—we are helping restore what injustice has tried to steal and honoring why HBCUs were created in the first place: to give Black people the education they were once denied.

Image: Pexels/Mika Photogenius

Add comment