During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kirby Hoberg noticed that her pastor began to give, in her words, “a lot of strange homilies.” These included “homilies that suggested that racism wasn’t real, that the pandemic wasn’t real, that viruses weren’t real.” In short, “a lot of fairly concerning things to have preached.”

Having moved to Minnesota with young children a few years before that, her family didn’t know anyone in the area, so church was a place where she’d invested a lot of time and energy, even serving on the parish council. But when she approached her pastor with her concerns, his reaction was virulent; he accused her of speaking out of turn and questioning his authority. In the following weeks, the parish essentially closed ranks around the pastor. Ultimately, Hoberg and her family left the church.

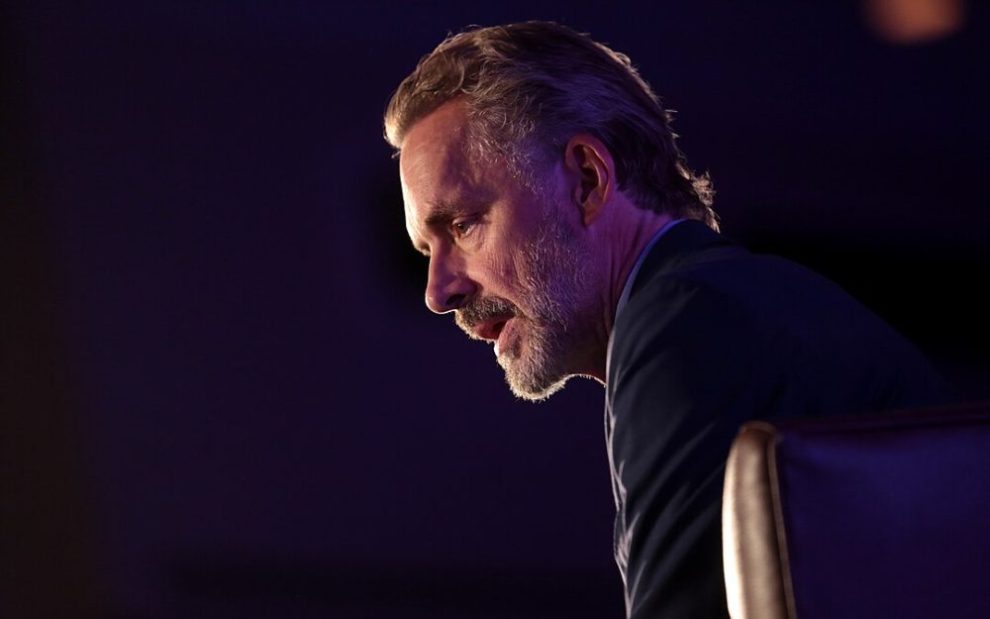

As this painful chapter unfolded, Hoberg says she felt the regional church’s power dynamics shift with the arrival of the new head of the Winona-Rochester diocese, Bishop Robert Barron, head of the media enterprise Word on Fire Catholic Ministries. In prior years, Barron engaged in public discussions with far-right figures such as Ben Shapiro and Jordan Peterson, even recommending the latter to other bishops. In Hoberg’s words, “He keeps highlighting people who, at best, just need to be left alone to figure this out quietly.”

What Hoberg experienced could best be understood as toxic masculinity. This umbrella term covers a range of beliefs and behaviors across cultures and in different forms. To be clear, toxic masculinity is not the same as masculinity itself. Nor is it simply an obsession with masculinity. Instead, we see masculinity turn toxic when, for example, men are raised to repress their emotions, then turn around and harshly impart the same habits to their sons; these men tend to act out performative objectification of women, entitlement to women’s bodies, and the belief that women should submit to men’s dominance. Some of today’s political views channel these macho ideals into prescriptive and repressive policy proposals against women and gay people, transgender people, immigrants, and other vulnerable groups.

These attributes are common among an online “manosphere” confederation of various podcast hosts, YouTubers, and other content creators. The trend shot to new prominence after President Trump successfully used it to pull new male voters his way in 2024. It continues to influence an audience of millions, including many Catholics.

Toxic masculinity shows up in church spaces, especially online spaces. It manifests in forms that range from domineering priests who embrace conspiracy theories to laypeople who are hostile to women and non-white people and cultures. Meanwhile, toxic masculinity’s beliefs and behaviors clash with actual Christian teachings on gender and masculinity. The healthy doctrine on how to live out the experience of masculinity—even humanity—gets obscured by this warped concept of what it means to be a man.

How toxic masculinity manifests

Sarah Riccardi-Swartz first began to be concerned about toxic masculinity in her church in 2017, as she worked with her fellow Orthodox Christians in Appalachia. When young men, recent converts to Orthodoxy, recommended influencers they followed online, she decided to check them out. What she found was content largely curated by men for men using Orthodox Christianity to promote ideas about the male body and the family while attacking things they didn’t like, such as feminism and gay marriage.

An assistant professor of religion and anthropology at Northeastern University in Boston, Riccardi-Swartz has been documenting these spaces ever since. She sees the “obsession with masculinity” as part of a reactive Orthodoxy that’s “incredibly conducive to radicalization.”

“The things that they’re teaching about Orthodoxy and about Christianity in general are so violently opposed to the message of the gospel that to me, it’s shocking,” she says. “Orthodoxy became malleable for them . . . to push their political views about masculinity through in really convincing ways for their audience.”

Riccardi-Swartz finds it curious that amid their strident claims of Orthodoxy, these influencers welcomed the commentary of Catholic far-right influencer Nick Fuentes, despite what they would term his so-called heterodox views. “Toxic masculinity knows no boundaries,” she says.

Catholicism also has a toxic masculinity problem, a reality that’s not lost on many Catholic thinkers and leaders. Megan McCabe, assistant professor of religious studies at Gonzaga University, says this reality’s main attribute is “access and entitlement to women’s bodies.” She notes the “violent gloating” in the aftermath of the 2024 presidential election with slogans like “your body, my choice.” McCabe concludes that it “sounds to me like rape.”

McCabe’s experience echoes the sense of “We’re so back!” that Riccardi-Swartz witnessed in far-right Orthodox spaces after Trump’s win. “In the United States, the Catholic Church . . . is participating in American culture war in a way that is presented as if the church is enforcing doctrinal teachings of gender,” she says. “But the views of gender that are being put forward . . . [are] actually not the [church’s] teaching of gender.”

She points out, for instance, that the Catholic Church teaches feminine-masculine complementarity, “which is supposed to mean equal” rather than male dominance. “The value of men as human beings cannot be put at odds with . . . the successes and value of women as human beings,” she says.

Ramon Luzarraga, associate professor of theology and religious studies at Saint Martin’s University in Washington state, mentions another lie behind toxic masculinity: that “feminists want me to be made less than they are.” He says that if you’re a healthy man, “you are comfortable with women in positions of power, because you don’t see it as a threat to your masculinity or your being a man.”

Riccardi-Swartz says that many of Orthodoxy’s distortions in manosphere spaces come from men who are recent converts from Protestantism. “They spend their time mining the texts of esoteric monks who live on the side of a mountain to find something that will justify their claim,” she says. “That’s not actually an Orthodox perspective on how to understand theology or the teachings of the church. That’s a very Protestant understanding.”

McCabe sees the wider cooperation of U.S. Catholics with authoritarianism—exemplified by Trump’s strong Catholic voting bloc—as rooted in “anger around gender in culture wars.” She cites Vice President JD Vance as an example; he projects an image McCabe describes as “somehow protecting some kind of family value that’s connected to gender, but it’s not.”

Problems close to home

At the local level, a renewed focus on manliness in ministry often takes the form of activities geared toward men, sometimes playing into stereotypes of what is considered manly: playing golf, drinking whiskey, smoking cigars, eating barbecue, lifting weights, growing beards.

Hoon Choi, assistant professor of theology and religious studies at Bellarmine University, says parish men’s groups can serve as powerful spaces for men to experience camaraderie and engage in community service. But he cautions that the vast majority of these groups’ leaders are not trained or interested in pursuing a holistic understanding of masculinity.

“They are also vehicles through which a lot of political agendas are pushed,” Choi says. “I think that many are politically charged, and I think that’s more pronounced in today’s climate. Anything that’s not heteronormative masculine is seen as woke ideology.”

Bishop John Stowe, the bishop of Lexington, Kentucky, has seen this same false masculinity at play in priestly formation. “A current emphasis on the manliness of candidates for the priesthood seems to be connected to the misplaced blame for the sex abuse crisis on homosexuality,” Stowe says via email.

“An appropriate emphasis on integrated and balanced psychosexual health is not served when the focus is mostly on externals,” he says, “and is even more problematic when certain ‘machismo’ characteristics—like the disregard of women’s opinions, thoughts, or feelings or the outright insulting of women—[are] tolerated, instead of experiences of shared ministry in which the perspective of women matters.”

“Gender is identified as a component of clericalism, along with sex and power,” says Julie Hanlon Rubio, professor of Christian social ethics at the Jesuit School of Theology at Santa Clara University’s Berkeley campus. “It’s important to acknowledge that structural clericalism operates in the church in part through unhealthy forms of masculinity.”

When Kirby Hoberg thinks about her family being basically driven out of the church, she sees the key factors as male insecurity and priests’ inability to engage women as equals. A cradle Catholic and a Native American (Ponca of Oklahoma), she’s also disturbed by white Catholics’ tendency to view her ethnic cultural practices as suspect.

“Why is it so hard for me to be seen as Catholic enough but so hard for you to be seen as not Catholic enough?” she says of this Eurocentric view, especially as the white Catholics in question embrace misogynist, xenophobic ideologies and call them Catholic. “No matter what they said or what they did or who they hurt, it didn’t matter because they were all part of the church.”

Based on her own Orthodox Christian experience, Riccardi-Swartz also sees a disconnect between the online world and how people show up on Sunday. “Some priests don’t understand what’s going on online at all,” she says. “What they’re missing is a young man who, online, will post Hitler praise, will post white-power stuff. Then he’ll come to church on Sunday, and . . . [h]e seems like a great guy. Who wouldn’t want him in the parish? What they don’t know is what he’s posting online.”

Positive male models as an alternative to toxic ones

If toxic masculinity is captured in part by a term like machismo, then that at least provides the church with a frame of reference for modeling an alternative.

“There are versions of it in lots of different cultures, and it’s important to know that John Paul II calls out machismo,” says Rubio. “Francis calls out problematic forms of masculinity and gender stereotypes. So we have in Catholic teaching tools for criticizing, for critically engaging cultural exaggerations that are really unhealthy and that are not Christian.”

As he builds an affirmative alternative to machismo, Luzarraga looks to his time as an adolescent at Holy Cross School in New Orleans, operated by the Brothers of the Holy Cross. The strictly enforced code of the school—which every student had to memorize—stated, “The Holy Cross man is a refined gentleman” and a “friend to all.” The practice of training boys to be gentlemen is a long tradition in the Catholic Church, Luzarraga stresses, one that teaches young men the meaning of true power in quiet, gentle ways.

“When we respond to anything that is evil or wrong or toxic, we respond to it as Christian gentlemen. We provide that ultimate way forward,” Luzarraga says. This distinguishes authentic masculinity from what many people mistake for manliness: “the raw, promiscuous, punitive use of power.”

Boys and men should look to the examples of men such as Jesus and St. Joseph, says Luzarraga.

“What you’re doing, always, is lifting people up” and being a servant to all. “You do that through the daily tasks by which the people around you flourish.” He adds, “People who display their so-called manliness are only displaying weakness. At a certain political convention, when a certain professional wrestler tore off his clothes, I thought to myself, that’s the mark of a defeated man.”

The “Holy Cross man” framework is also antithetical to the Jordan Peterson maxim that, rather than striving to be a good person, men should be monsters who learn to control themselves. “[That] basically says that we are somehow beyond redemption, and that’s certainly not Christian,” Luzarraga says.

The same goes for attitudes that seek to dominate women. “With toxic masculinity,” Luzarraga says, “there is this sense that men always have to be the active agents in everything in their dealings with women. No! A true gentleman always welcomes the active, proactive moral agency of women.”

Another facet of toxic masculinity that puts it at odds with Christianity, says Choi, is its insistence on only one model of how to be a man. Choi believes men have shared embodied experiences—including physical stages and phenomena such as puberty and physical arousal—that naturally create shifts in how they express their masculinity throughout their lifetimes. All these changes, Choi says, reflect the mystery of inhabiting a particular body. These experiences, while sometimes uncontrollable or unexpected, still reflect God’s grace. They tell “you something of what it is to be a man,” he says.

“In all the ways in which we’re men, God can be made visible,” he says. “Different rays of masculinity will enlighten us.” This includes the church’s embrace of celibacy as a countercultural model, but it also extends to spectrums that embrace the many possibilities of both lived masculinity and gender.

The gateways to toxicity, says Choi, are shame and societal or religious taboos that keep men from speaking candidly about their shared experiences, leading them to cling to one overly prescriptive model. These taboos can be counteracted, he notes, by gaining a larger perspective. If we zoom out to perceive the whole world, we see how different cultures—even the Catholic ones—approach being a man differently.

Choi cites his own Korean culture and the phenomenon of K-pop as one completely different approach. K-pop performers “wear makeup, what in American culture might be considered feminine,” he says. “It’s really easy, actually, to see versions of masculinity different from Western, heteronormative model masculinity.” Grasping this variety is one healthy way to counter the white, Eurocentric view of toxic masculinity. “And,” he says, “you may learn something from it!”

Focus on humanity, not masculinity

One challenge Julie Hanlon Rubio recognizes as she defines healthy masculinity is that the necessary qualities ultimately are the same as simply being a good Christian. “My own default is less healthy masculinity and more good humans,” she says.

One of the pitfalls that can contribute to a toxic view is the impulse to reject any qualities traditionally regarded as feminine, such as being compassionate, in touch with one’s emotions, and gentle. However, Rubio says, in reality, “no one would want to be the opposite of the feminine genius.”

Megan McCabe hopes that today’s boys grow up realizing their “value as a human being that is not contingent on . . . gender.” Young men are in pain today, she says, due to “not having a sense of inherent worth,” while misattributing that to a sense of being displaced as the dominant group. She calls for a change in the masculine notion of success; men have “to be able to like being equal with women, not dominating women.”

In discussions of toxic masculinity, Kirby Hoberg says, we can’t lose sight of women’s role in enabling domineering men, acting as if they don’t have the power to stop them. Historically, many white women supported segregation, and now, she recognizes, “we’re in that situation with misogyny in the church as well.”

Rubio acknowledges differences in how men and women live out their identities. “It’s important to take embodiment seriously. Embodiment matters,” she says. However, “those differences are much smaller than the commonalities.” She contrasts the relatively short duration of bearing and nursing her children with the decades of common experience of parenting alongside her husband. “I wish we could focus on the deeper question of being a good human more.”

She adds, “Catholic thought, if you really read the documents, it’s less gendered than people might expect. . . . The tradition is far less prescriptive than, say, some guy in the parish or out on the blogosphere. . . . We have less to say than one might think about masculinity and femininity.” And in the space that creates, maybe people of faith can find room to step back and realize: “It’s much bigger than the binary.”

This article also appears in the May 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 5, pages 10-15). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Jordan Peterson, Wikimedia Commons/Gage Skidmore (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Add comment