To love. To resist. To care for others. To work. To revolt. To live. To rest. All of this, according to Gloria Browne-Marshall in her new book, A Protest History of the United States (Beacon Press), are forms of protest.

The book lays out more than 400 years of protest in the land that is now the United States, starting with the Powhatans, who protested the Jamestown settlers taking their land and resources, and moving through those who protested enslavement, labor conditions, a lack of women’s rights, and war, each movement carving out rights that today we take for granted.

The main takeaway of Browne-Marshall’s book is that protest isn’t something delegated to professional community organizers or the few people remembered by the history books—figures such as Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, Susan B. Anthony, or Mother Jones. We all have the capacity to be protesters. “All of us can do something to push justice forward,” she says. “We can’t wait for some other group, some other time, some other place.”

Today, women and Black Americans have the right to vote. Jim Crow laws are a thing of the past. Our workdays last eight hours. Children don’t work in the mines. There is a minimum wage. All these basic protections were won by protesters, people just like each of us who were not afraid to put their safety on the line to make the world better for those who came after them. But the struggle is not over, Browne-Marshall says. Just as these courageous ancestors did for us, we too have the responsibility to make the world better for those who come after us.

What is protest?

Protest is defiance of oppression and a push toward social justice, human rights, human dignity, and equality under law. It can be defiance of expectations, defiance of prejudice, or a fight against oppression. But it can also be that someone sees the need for an expansion of rights and acts in defiance against any obstacles standing in the way.

I decided that my book, A Protest History of the United States, would focus on the push for expanding rights and equality as opposed to those who protest the expansion of those rights. So, in my book, protest is not oppression by people in positions of power wanting to maintain some artificial superiority over another group or person.

If a person is thought to be a workhorse, and they’re only supposed to work and make no intellectual contribution to society, their decision to rest may be a protest. Think of what happened during enslavement, when enslaved people broke their tools to say, “I’m more than just a perpetual laborer. I’m going to break this tool so I can rest; I’m going to defy the law and the expectation that there’s nothing more to me than to work for someone else for free for generations.”

What’s the relationship between protest and civil disobedience?

Civil disobedience is a form of protest, but protest can take many forms. One reason I wrote this book is because I have watched, over the past 15 to 20 years, this idea arise that there is something called a community organizer, or a professional activist, and they’re supposed to do the work of civil disobedience. There’s this sense that they are responsible for making change. People will say, “Well, I’m not an activist. It’s not for me to make something different happen,” and it’s almost as though they have capitulated.

But protest isn’t just about a set group of people who do all the work while others live their lives. Think about the demonstrations for women’s rights. As two women talking right now, we are able to have this interview, to hold the positions we hold, because of professional protesters. Each individual has an opportunity and a responsibility to do something from where they stand.

Protest isn’t always a big rally. Some people’s act of defiance, because of their circumstances, may be very small. But all of us can do something to push justice forward. We can’t wait for some other group, some other time, some other place—as though we don’t have an obligation to participate in the movement of our communities to a better place.

On one hand, it’s great that activism and protest are being recognized as something important, something people should get paid for. But on the other hand, you’re right: That takes away the responsibility for protesting inequities from everyday people.

I began in civil rights. My first job—after a state and a federal clerkship—was at the Southern Poverty Law Center. It wasn’t until I learned about civil rights cases that I saw meaning in law. I became interested in how we use the power of and philosophy behind law and how the law is used, especially constitutional law in U.S. Supreme Court cases.

People would tell me, “Oh, you’re a civil rights attorney. That’s great—I’m so glad there are people like you doing the work.” And initially I was honored and flattered. But then I got kind of irritated at the idea that all this work was supposed to be dumped on people who had a job called “civil rights attorney” or “community organizer.” In reality, teachers, sanitation workers, ministers, priests, rabbis, even children—all these people played a role in creating the rights we take for granted today.

As I see these rights currently being chipped away, I realize that we need a better and broader understanding of what an activist is. It’s not a job. For the most part, people become activists because something happens to them. All of a sudden, they see their own fate in the context of a broader landscape. And they act.

Any act in which a person pushes for equality and justice is activism. But sometimes that title is too heavy for people to bear. There’s this vision of an activist as someone out in the street with a fist in the air. But some people don’t see themselves that way. Or maybe the word activism seems like something that will have them fired, ostracized, or labeled as troublemakers. Some might prefer to stay quiet until there’s a trigger. Even when people are forced into activism, many never saw themselves as having the qualities of an activist.

You write that “protest is almost inevitable in the United States.” Why is protest so linked to what it means to live in this country?

The United States has set itself this standard of being a shining light on the hill of democracy. But it has these conflicting personalities. One speaks of liberty and justice for all. But when they signed these words from the Declaration of Independence and espoused liberty into our earliest laws, that same government was oppressing and enslaving people of African descent and Indigenous people.

The U.S. government is set up for protest. The Constitution and First Amendment don’t just guarantee freedom of speech and freedom of assembly—they guarantee the right to petition the government for a “redress of grievances”—that is directly from the First Amendment. We have a right to demand of our government that it fix things. This sets the stage for protest to become an indelible part of the United States.

What impact have protest movements had in this country?

The eight-hour workday is a very simple thing that many of us take for granted. But for almost the entire history of the country—for longer than the history of the country—we did not pay people for their labor. We paid immigrants much less. We paid citizens less based on the color of their skin. We paid women less or didn’t let them work at all. And we did all this in the context of a 12- to 16-hour workday.

Our average workday today depends on people protesting. We have safe work environments because people protested after events like the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, which killed 148 garment workers—mostly women and girls—because the doors and windows were locked to prevent them from taking breaks. We don’t have children working in factories anymore because of labor protests.

I think many people believe that the safe work environment we all have, the protection from discrimination in our jobs, just fell out of the sky. That people in positions of power just felt generous one day and gave these rights and protections to employees.

In reality, these rights were fought for. People died. They were beaten. They lost their livelihoods. Their families were torn apart.

Take coal miners in West Virginia. It used to be that the mining company owned the land, the school, and the store. If there was a protest, those protesters lost not only their community and friends, but were also evicted from their homes. Their children couldn’t go to school. And because the mining companies owned all the land, there was nowhere for them to go. They couldn’t even camp in tents.

And, despite this, the miners protested because they wanted to form a union, so they could have better wages and better working conditions. This is what a protest is: It is saying. “I want to defy the horrible way in which I’m being treated. I’m going to rise up and join an organization that gives us a stronger voice so that we can speak up in powerful ways and have a seat at the table to negotiate how we are treated.”

These negotiations are another act of protest. They say that people defy the narrow box of treatment they’ve been given and are trying to have more. They are working to expand the rights and protections that human dignity says one should have.

How might protests look different for those with privilege or power?

What does it mean to be privileged? Is it somebody who has more money or education or influence than someone else? That could be anyone. Is it someone who is extremely wealthy and has connections in high levels of government?

Martin Luther King Jr. was privileged. He was a person with a doctorate degree at a time when many white people did not have them. He came from an established middle-class family in Atlanta. He did not have to get involved in activism; he would have lived a life somewhat more privileged than that of many African Americans across the country, especially in the deep South. Yet he chose to be involved.

Each of us can see ourselves as privileged if we’re not being harmed at the time. Take, for example, homelessness. If we have a home, warmth, and food, then we’re privileged compared to someone who is out in the cold or a family in a shelter. Maybe it’s time to expand the idea of what privilege is; it’s not just about the extremely wealthy.

Maybe the privileged are those who, as they say, “don’t have a dog in the fight.” They can watch an issue on television and turn it off, see it on social media and decide to keep scrolling. Those people have a role in justice movements.

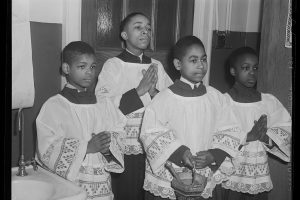

Religion can teach people how to act in the face of oppression. If someone’s faith teaches them to treat their neighbors as they want to be treated, that leads them to say, “That is my sibling being harmed. Therefore I must do something.” And we’ve seen this in many instances, when those people standing up were not the ones actually being oppressed. In 1859, John Brown was led by his religious faith to fight against slavery. In the 20th century, men were led by their faith to stand up for women’s rights. During the Vietnam War, people not affected by the draft got involved in anti-war movements.

It seems to me, from my context as a white Millennial, that there was a lull in protests after the era of civil rights and anti-war protests, and the current era of protest started with Occupy Wall Street. Is this accurate?

Well, African Americans have been protesting this entire time: They haven’t stopped. So, yes, for many people in the country, it seemed like there were protests against the Vietnam War and then Occupy Wall Street. But people of African descent have been always protesting police-involved civilian assaults and shootings, education, housing, and employment discrimination.

I think Occupy Wall Street was different in that it involved middle-class white people who were questioning whether they had a role in the country in the way other generations had—whether they would have viable careers and the middle-class life their parents had.

What does a successful protest look like?

A successful protest is one in which no one gets hurt. It allows the issues to have a voice, and for those voices to be heard by the opponents or oppressors. It results in change that is in line with what the protesters have asked for.

Sometimes a protest by itself may not be as successful as protesters want because a protest has a very long tail. They might not see immediate change and believe a protest has failed. But change can be decades long in the making. When change happens, it can be one last tipping point of protest that leads to a change.

It took decades to get the eight-hour workday—from the 1800s to the early 1900s. It took decades for women to gain the right to vote: from Black women who met in Philadelphia in the early 1840s to the women who met at Seneca Falls in 1848 all the way to the 19th Amendment in 1920. That last wave of protests gave women the right to vote and changed the Constitution, but those decades beforehand all chipped away at the oppression.

People in positions of power who have the ability to oppress others and suppress their rights, to confine people into cages of inequality, also have the means to maintain the oppression. For protesters to chip away at that takes time.

Think about same-sex marriage and gay rights. That took 50 years. It might have seemed like it happened in the last five years and all of a sudden we had Obergefell v. Hodges. But it actually started with Stonewall in the 1960s.

A successful protester may not ever see the end result of their protest. We need to invest in protesting and see it not as something that leads to immediate gratification, but something that is a stream. We each put our leaf, our twig, into the stream. And we look forward to someone downstream getting the benefit of our work.

There’s something both comforting and really depressing about that.

It can be very depressing if you’re the person putting in the work at the top part of the stream. But it’s wonderful for the person downstream getting the benefit of your work. But the stream is always flowing; you and I have received a benefit from people upstream who never knew our names. Think of the women who worked for us to have the jobs we have at this moment.

We benefit from past protesters. We don’t know who they are, they don’t know who we are. They just did the work. That’s an understanding that’s missing today; people want to see the benefit of their work right now.

Are successful protests still happening today?

People sometimes think that protests are no longer effective as a tool for change. But I disagree. Protest needs to be part of an overarching strategy. A protest can’t be just a spontaneous thing; there has to be a vision. It doesn’t even have to be a single vision: Martin Luther King had one vision, Malcolm X had one vision, Noam Chomsky had one vision.

King and others were so effective because they brought together different elements and had an overarching strategy. The Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965. Maybe some people thought, “Well, there was a march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, and now we have voting rights.” But the fight for voting rights had been going on for 50 years. People died registering folks to vote. Buildings were burned.

The March was important because it brought local, national, and international media attention to the need for change and the oppression of people of African descent and other people of color who were being denied their right to vote. But it occurred alongside proposed legislation, litigation by the NAACP and other organizations, and more.

One example of a well-organized protest movement today is the protests for unionization at Amazon. It’s easy to look at the U.S. Supreme Court conservative supermajority and assume there will be no movement. And the courts have certainly limited the success, saying that the unionization of Amazon employees is limited to each individual site; they have to go from business to business organizing instead of having a union across all Amazon distribution sites. But despite that, change is happening.

The people who’ve led this success have been harassed, lost their jobs, suffered all the consequences that have happened in the past when it comes to labor protesting. And yet, all those things aside, the moral arc of the universe bends toward justice.

See, here’s the thing, the universe doesn’t bend toward justice. It’s the moral arc of the universe that bends and, in doing so, forces the universe to be more just. And this is what’s going on with Amazon and these other very wealthy people who are abusing their employees and not allowing them to unionize. We’re going to start to see the ball rolling.

What gives you hope when it comes to the future of protest?

There is a quote in my book: “The oppressed worker will not remain crushed under the boot of trillionaires, billionaires, or their less wealthy minions. Protest, rebellion and resistance will be the human choice.”

The human spirit inside each and every one of us cries out for justice. That is not going away. And that’s why I believe protest is primal. Every individual will eventually get to the point where enough is enough, where they have to speak up for their family, friends, community, or themselves. Some people’s trigger points might be deeper inside than others, but everyone has one.

Other people have a sense of communal spirit, where they put their individual needs second to their community, their family, their church, or their beliefs in the service of social progress.

There is gratification in seeing that the activist is not that person over there who’s supposed to do all the work. Each of us has something that we’ve been given by God to do. Martin Luther King teaches us that everyone can play a role: You don’t have to be an educated person. You don’t have to be in the front of the line. I always go back to Rosa Parks: She just sat down and refused to get up. She wasn’t in the street with a bullhorn, yet she’s remembered for that act of defiance and protest.

We just have to recognize that we are not planting a tree so that we ourselves receive the shade, but so someone down the line receives that shade. That’s crucial.

And while instant gratification can crush any protest movement, there is something so powerful about people coming together with a shared belief. That communal spirit of marching shoulder to shoulder is something that has to be felt. There’s a buoyance to that, a sense of freedom. It makes one feel like they’ve done something to make their country, their community, a better place, especially when it’s done so nonviolently. There’s a camaraderie of purpose that gives one hope.

Being part of history in that way is also very important for the ego, if nothing else. To be in the March for Women’s Rights and be able to say, “I was there”—that matters.

This article also appears in the March 2025 issue of U.S. Catholic (Vol. 90, No. 3, pages 16-20). Click here to subscribe to the magazine.

Image: Unsplash/Alex Radelich

Add comment